Separated At Birth: Library and Publisher Metadata

METADATA MEETING Douglas County’s Julie Halverstadt (l.) and Nancy Kall confab beside the Metadata Mission Control whiteboard used to track incoming publisher data. Photo by Laurie Van Court

The Douglas County Libraries’ (DCL) pioneering project to own, rather than license, much of its e-content has not only forged a new business model but also exposed a new frontier in metadata. As of March, about 22,000 of the library’s nearly 58,000 e-content titles had been purchased directly from publishers and stored on an Adobe Content Server (ACS), and it became quickly apparent to library staff that we were going to have to get creative with the metadata associated with this material.

The metadata

Our charge was to add e-content received directly from publishers (25 publishers and growing) to our collection rather than acquiring it through traditional channels of e-content providers who play the role of intermediary between publishers and libraries.

Bib Services had previously dealt exclusively with MARC data. We use SirsiDynix’s Horizon, and from the early days of providing e-content to our patrons available through such providers as OverDrive and Gale Reference, we have always included MARC records in our integrated library system (ILS) catalog. However, it became obvious that we needed to be able to accommodate other metadata formats apart from the MARC format for one glaring reason: most publishers were not versed in MARC, the library world’s standard for metadata. While a few publishers did establish relationships with MARC processing companies and were able to provide us with MARC files, the majority did not.

The XML-based ONIX (ONline Information eXchange) is the metadata format endorsed by publishers. We were aware of ONIX-MARC crosswalks, but we were not familiar with any details. However, we also determined that not all the publishers were even versed in their own industry’s metadata format, so we needed to pursue other options. We had been using the freeware product MarcEdit for relatively simple editing of MARC files, such as those provided by OverDrive, and understood many of the capabilities of this powerful tool. However, the sense of urgency in gearing up for our ACS e-content project and getting records for the titles we were purchasing into our catalog for discovery made us realize that we needed to pursue other functionality provided by this versatile MARC editing tool.

MarcEdit supports the ability to integrate separately developed XSLT (Extensible Stylesheet Language-Transformation) stylesheets for crosswalking different types of metadata from one format to another, specifically ONIX to MARC, but we had no experience in how it worked. Early on we received sample ONIX files from different publishers, and we quickly saw that not all ONIX files are created equal. We needed a robust capability to crosswalk ONIX data elements provided via XML files received from different publishers to MARC fields and subfields.

We were fortunate to find a consultant, Dana Pearson, who helped to develop and refine such an ONIX crosswalk capability. Using as a basis the OCLC ONIX-MARC crosswalk that is similar to that defined by the Library of Congress, Pearson developed and has continued to enhance both ONIX 2.1 and ONIX 3.0 crosswalk versions that allow us to be flexible in supporting different flavors of ONIX files that publishers provide. Pearson used the XSLT technology well suited to XML ONIX, to create the crosswalk.

The third category we investigated was spreadsheet metadata. We explored the MarcEdit delimited text translator used to define a translation table that maps predefined spreadsheet columns to MARC fields/subfields. While we preferred to receive either MARC files or ONIX files, we found that many publishers were only able to provide us with metadata in spreadsheet format.

In our initial communication with new publishers, we inform them that we can accommodate three different types of metadata formats (in order of preference):

In our initial communication with new publishers, we inform them that we can accommodate three different types of metadata formats (in order of preference):

This is when that good working relationship becomes critical; after all, we are courting new publishers and definitely want a “second date.”

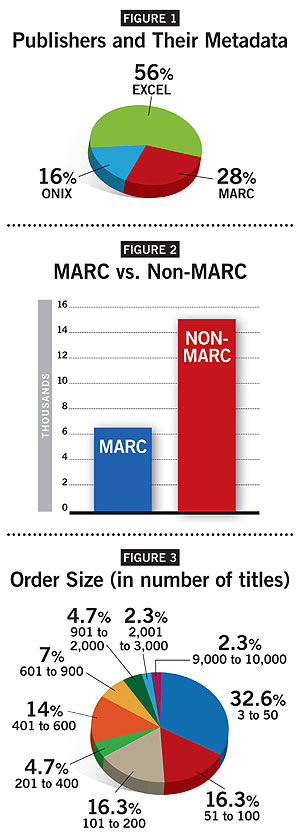

Figure 1 reflects the analysis of metadata that publishers provide us. Interesting to note is that over half of the publishers send us metadata via Excel spreadsheets.

Of the 22,000 ebook titles (EPUBs or PDFs and associated cover art) managed directly through our ACS server and VuFind discovery layer, about 7,000 (31 percent) of these titles began their life in the MARC format (see Figure 2). A handful of these titles, about 70, were ordered individually through publishers, for example Smashwords or Colorado Independent Publishers Association (CIPA), and original MARC records were individually created through the OCLC Connexion interface. Also, in a few cases of small add-on orders from existing publishers, we were able to find existing records in OCLC’s WorldCat for the titles and elected to download these versus waiting for metadata from the publisher. However, this was not frequently an option as often we could not find records in OCLC, or we would order and receive hundreds, even thousands, of titles at a time. We needed to add records to our catalog for titles ordered as quickly as possible so they could be available for patron checkout.

The remaining 69 percent, or about 15,000 titles, began their life as either XML data in an ONIX file or as rows in an Excel spreadsheet, and these files were either crosswalked (ONIX) or translated (spreadsheet) to MARC records.

Hitting the Ebook MARC

When processing incoming ebooks, ensuring that the titles can be easily found on a library’s OPAC is a top priority. At the most basic level, this means properly cataloging each item, but the free MARC records provided by publishers often include little information beyond an ebook’s title and author.

On-site copy cataloging tends to be impractical, particularly for small libraries or large orders. While OCLC can provide MARC records for ebooks, many subscribers must still pay an additional charge for this service. There can also be significant delivery delays when OCLC doesn’t already have a record prepared for a specific item.

Scott Reinhart, assistant director for operations for the Carroll County Public Library (CCPL), MD, notes that those delays can also make it a challenge to keep track of which ebooks have MARC records associated with them and which do not.

“There’s no way we would know, in any given file, [which MARC records we had] received and what we hadn’t received, versus what we had already purchased through OverDrive,” he says.

In the past ten months, vendors have launched two new services that address these issues: eBiblioFile, introduced by The Library Corporation (TLC) in July 2012, and eMARC Express, introduced by SkyRiver in October 2012. Both services offer fast turnaround of MARC records compatible with all major integrated library systems (ILSes) for ebooks purchased via OverDrive or 3M’s Cloud Library platform.

“When we first started testing to see if there was a market, we asked libraries if they had an easy way to get their ebooks into their catalog, how long it was taking, and how much it was costing them,” says Gar Sydnor, senior vice president for TLC. “The answers to those questions were no, they didn’t have an easy way; it was taking them, using their various methods, a long time to a very long time; and it was costing them a lot more than they wanted to spend.”

Tom Jacobson, director of resource sharing for SkyRiver parent Innovative Interfaces Inc., agrees. “It’s a lot different from the old days when you took a book out of the [shipping] box and cataloged it. Here, you’re buying 10,000 ebooks and they’re instantly available. Why can’t we get them instantly cataloged?”

With eBiblioFile, TLC promises to deliver Library of Congress MARC records modified for e-resources within 48 hours of purchase for $1 per record. Records can include custom headings and fields, as well as URLs linking the record directly to the OverDrive or 3M item. Through arrangements with 3M and OverDrive, the $1 fee is simply added to the total cost of an ebook.

“It is a seamless process, meaning they just let their ebook vendor know ahead of time that they’d like [eBiblioFile] to process their MARC records, and they let us know the particulars of their library, such as what collection to put them in,” says Sydnor. “That’s all they have to do. Every time they place an order we get notice of that and deliver the records to them via email.”

If a full MARC record is not immediately available for a specific item, a minimal record is sent for free as a placeholder. TLC’s cataloging staff then manually create full records as replacements, using a proprietary algorithm to prioritize the order in which missing records are addressed.

SkyRiver’s eMARC Express shares some similarities. “It’s designed to be supersimple, superlow barrier to participation,” says Jacobson. Libraries sign up for the pay-on-demand service

on SkyRiver’s website and then submit purchase manifests or have them submitted on their behalf. Like eBiblioFile, it is a pay-on-demand service with no ongoing subscription fees.

SkyRiver’s eMARC Express offers three-day delivery for full MARC records derived from SkyRiver’s databases for 85¢ each, or 75¢ for existing SkyRiver subscribers. There is no charge

for MARC records created only from vendor metadata.

“We were paying a $1.50 through OCLC, and it’s $1 through eBiblioFile,” says Reinhart, who is also head of Maryland’s Digital eLibrary, a consortium of 23 systems that purchase e-resources together. “The records are pretty much the same, and for 50¢ less [per record], it was pretty easy” to make the selection. Reinhart said that the consortium was familiar with eMARC Express, which launched several months after eBiblioFile. But thus far, it had been happy with its current service, and “we saw no reason

to change.”

The service has grown quickly. Perhaps owing to its generous pricing scheme for consortia and buying groups—buy the record once, and it can be distributed to all members— almost 300 library systems and consortia now use eBiblioFile, including the Toronto Public Library and New York Public Library.

“I can’t say that pricing [for consortia] is going to stay in effect forever,” says Sydnor, “because we’re trying to align our pricing with whatever OverDrive is doing. But for now, it’s a pretty good deal.”

Matt Enis (menis@mediasourceinc.com; @matthewenis) is Associate Editor, Technology, LJ

We were curious about the distribution of order size, specifically the percentage of large orders to small orders placed with publishers. Figure 3 illustrates the size distribution in terms of number of titles in metadata files we have received for ACS content. (It does not include the 70 or so titles mentioned above that were ordered individually from different publishers or directly from authors.) Since much of the metadata creation and editing is done via batch processing, this means, generally, that it takes close to the same amount of effort to create final metadata for a small order (e.g., 100 titles) as it might for hundreds or thousands of titles.

To date we have placed two orders of ACS e-content that were in excess of 2,000 titles each. One of these was for 9,637 titles, placed with Smashwords. The publisher delivered 19 ONIX files to us containing about 500 records each. We added about 1,000 titles to our catalog at a time.

Metadata opportunities

Expediency requires batch-loading of records, but there are always inherent challenges in maintaining the quality of metadata, as it is not practical to review all individual records. Even when the metadata begins its life in a MARC format, batch-editing is required to some degree. There are two categories of batch-editing we perform. The first category is to clean up metadata we receive from publishers. This could be as simple as adding basic fields that are missing in MARC records we receive from a specific publisher to identifying and correcting in ONIX or spreadsheet files characters that are not recognizable by our Horizon ILS system. This is very publisher-specific. Apart from editing to improve quality and consistency, we also add basic fields to all e-content records in our catalog, including a publisher-specific local genre heading (e.g., Downloadable Smashwords ebooks). This allows us easily to identify and track titles in both our Horizon system and our VuFind discovery layer we have received and processed from any particular publisher. This likewise helps public service staff locate specific e-content titles more readily, and this tip has been passed along to patrons.

When metadata begins its life in a non-MARC format, as in the case of ONIX records and spreadsheets, by default nonlibrarians create the metadata. This introduces additional challenges. These include:

SUBJECT HEADINGS The publishing industry doesn’t acknowledge the Library of Congress (LC) Subject Headings, the library world’s standard. Rather, it endorses BISAC (Book Industry Standards and Communications) subject headings. Publishers include at least one, and often more, of these BISAC headings in the metadata they provide to us. NAME HEADINGS Again, name headings are provided in the metadata that are inconsistent with those of the LC NACO authority file. So if we have both the ebook and physical book of a particular title in our catalog, they may not be collocated under the same author name. Also, it is not uncommon to find headings formatted as “Kemper, Kathi J., MD, MPH, FAAP” or “Sweeney, Susan, CA, CSP, HoF”, or even a corporate name in inverted format, e.g., “Press, HowExpert” versus “HowExpert Press.” SPECIAL CHARACTERS Publishers typically copy/paste book descriptions from those that have been developed for display on the web. As a result, they can contain HTML tags as well as characters from the UTF-8 character set that has become the dominant form of character encoding for the web. This is problematic for traditional MARC-8 library systems like our Horizon product. If not addressed before loading the records into our catalog, characters outside of the MARC-8 character set will appear as “junk” in the display. However, MarcEdit has the capability to allow libraries to account for these. We have documented so far more than 50 of these non-MARC-8 characters that we automatically change through MarcEdit, and the list continues to grow. Some UTF-8 characters present more challenges than others. Curved quotes, or as they are sometimes referred to, “curly” or “smart” quotes, are an example. This treatment of characters outside the MARC-8 character set might seem a trivial issue, but characters such as these can cause major upheavals if not accounted for, and patron searching will be affected. MANAGING RECEIPT OF METADATA AND EPUBS/COVER ART Libraries have created and refined quite efficient workflows over the years to manage the ordering and physical receipt of items that are added to the library’s collection, including the step of obtaining metadata so that these resources can be discovered in the library’s catalog by patrons. This workflow does not directly translate to the e-content world where virtual content is stored and managed locally on a server. Often the metadata titles we receive do not match the content files that have been sent, and neither may be the same as the titles ordered. This could be because a title ordered one day may no longer be available the following day or whenever the EPUB or PDF file and/or the associated metadata is delivered. Another aspect is that we are dealing directly with publishers, many of which have never worked directly with libraries before. We are developing a new process, just as they are, in order to facilitate e-content acquisition and delivery. To begin to address these issues, DCL has been one of the partners in a venture to develop an e-content Acquisitions Dashboard.Managing the process

When we initially embarked on our efforts to support the district’s goal of acquiring, providing, and maintaining e-content on our ACS server, we developed a working document entitled “Econtent Metadata Processing Guidelines.” This detailed working document incorporates all the steps involved, including some described in this article, that are critical to our e-metadata process. Along the way, it has expanded from 16 pages to around 30 and is still designated as “draft.” We continually refine it as we bring new publishers onboard.

Bib Services asked to be copied in on any initial contact with publishers so no time was wasted in communicating with them about metadata requirements. We informed them of our requirements as early as possible and also requested that they send a sample metadata file for testing and approval. At the outset, our goal has been to establish a solid working relationship with publishers and their cataloging partners, sometimes beginning with a phone call to break the ice. Given that we were constantly pursuing any number of new publishers, we needed a way to keep track of where all publishers were in the order and metadata process, so we installed two large whiteboards in the cataloging area that served as our metadata “mission control.” On this board we keep track of all publishers, status of orders, and status of the metadata (waiting for or received) and note any issues with files received.

Early on we set up an “e-content tracking” spreadsheet on our shared server so that any library could check at its convenience the number of orders and the titles we had added to our catalog. This Excel spreadsheet incorporated one worksheet per publisher, in addition to a TOTALS worksheet that was an accumulation of titles added for all publishers.

An added challenge was that we were unable to add any new staff for this mission-critical project. We needed to find a way to work it into the already full schedule of existing cataloging projects.

What’s next?

There is an urgency in making newly acquired e-content available for patron checkout as quickly as possible. This means we frequently do not have the required time to do all the “cleanup” of MARC records loaded into our catalog that we would prefer to do. As described above, we do a certain amount of batch-editing of records using MarcEdit to globally add, change, or delete fields or subfields and also do some initial cleanup of name headings and book descriptions once the records are imported into our catalog, time permitting. However, database maintenance projects are planned to refine these records further as cataloger time is freed up from our outsourcing of copy cataloging. These include the following:

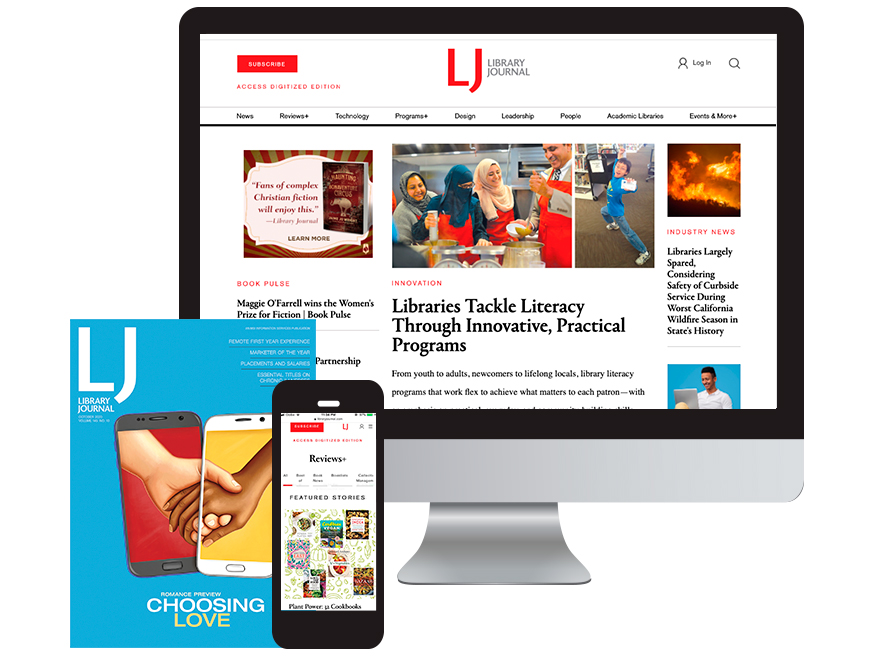

Name headings and series headings need to be reviewed to ensure they are in the proper form to conform to NACO headings. BISAC subject headings continue to appear more and more frequently in all types of MARC records we import, for physical as well as digital materials. Sometimes these headings included in MARC records for physical materials and those in e-content records may not be formatted identically. As a result, split headings occur in our Horizon database as illustrated in the screenshot from our catalog display (Figure 4). These need to be combined for efficiency of searching and display and would be required even if it weren’t for our non-MARC e-content records. A final objective will be to update our holdings in OCLC for our e-content titles. This will be done, one publisher at a time, in a batch process after we have completed our planned cleanup projects.

BISAC subject headings continue to appear more and more frequently in all types of MARC records we import, for physical as well as digital materials. Sometimes these headings included in MARC records for physical materials and those in e-content records may not be formatted identically. As a result, split headings occur in our Horizon database as illustrated in the screenshot from our catalog display (Figure 4). These need to be combined for efficiency of searching and display and would be required even if it weren’t for our non-MARC e-content records. A final objective will be to update our holdings in OCLC for our e-content titles. This will be done, one publisher at a time, in a batch process after we have completed our planned cleanup projects. We continue to refine our process of adding new e-content records to our catalog. As we work with new publishers we occasionally need to fine-tune our procedures and adjust our crosswalk. We have also become creative and proficient as a result of experience. We’ve become pretty good at the task of preparing for, receiving, processing, and loading e-metadata, as we have also become smarter and more efficient along the way. Despite challenges, the processes we outline here are part of those that will shape the future of cataloging. Dealing with forms of metadata other than MARC will be the norm for catalogers and metadata librarians. Use of macros, managed tasks, and other functionality available in tools such as MarcEdit automate the process to a large extent, allowing catalogers to focus efforts on what catalogers have always done best, description and classification of content, whatever its form.

Metadata in all its many forms is our bread and butter. After pushing through some initial challenges and frustrations, this new frontier feels more and more like home.

Julie Halverstadt is Bibliographic Services Department Head, and Nancy Kall is Senior Catalog Librarian, Metadata and Special Collections, Douglas County Libraries, Castle Rock, CO

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!