News

While there are many botanical gardens across the United States, only one has the distinction of being a tropical botanical garden chartered by the U.S. Congress: the National Tropical Botanical Garden, located in Kauaʻi, Hawaiʻi.

Dr. Colleen Shogan took the oath of office as the 11th Archivist of the United States—the chief administrator of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)—in May 2023, succeeding former Archivist David Ferriero. She is the first woman to permanently hold the role. LJ caught up with Shogan to hear about her national tour of presidential libraries, NARA’s stepped-up digitization efforts, and preserving the record of presidential cat Socks.

For fans of Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick, the name New Bedford, MA, may ring a bell, since it’s where Ishmael, the main character, signs up for the whaling expedition. The city is also home to the New Bedford Whaling Museum, which was founded as the Old Dartmouth Historical Society in 1903.

On November 2, 1929, at Curtiss Airfield in Valley Stream, NY, 26 female licensed pilots, mostly from the East Coast, gathered to form the Ninety-Nines, an organization dedicated to support and advance women in aviation. Famed aviator Amelia Earhart, the first president of the Ninety-Nines, came up with the name in honor of the 99 charter members. Almost 95 years since its founding, the Ninety-Nines has about 7,000 members in 44 countries.

In recent years, the scholarly nonprofit Ithaka has prioritized advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), both within the organization and in its outward-facing work. As that process evolved, Kate Wittenberg, managing director of Ithaka’s digital preservation service, Portico, saw that its archival conservation mission aligned in many ways with social justice ideals. In summer 2021, she began to identify underrepresented community collections that might be at risk without a preservation strategy, and in 2023 Portico launched a pilot project connecting the curators of those archives to its expertise and resources.

Chicago’s Adler Planetarium, which opened on May 12, 1930, is the oldest planetarium in the Western Hemisphere, and holds one of the largest collections of historic scientific instruments in the world, as well as rare books, manuscripts, archival materials, models, and photographs. Max Adler, the institution’s namesake, purchased and donated the initial collection of instruments, which included sundials, astrolabes, telescopes, and a projector.

As an archivist and division manager at Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History, Derek Mosley sees his work as an opportunity to preserve the stories of everyday people, ensuring that diverse records fill our cultural context and contributing to a more extensive portrait of African American life.

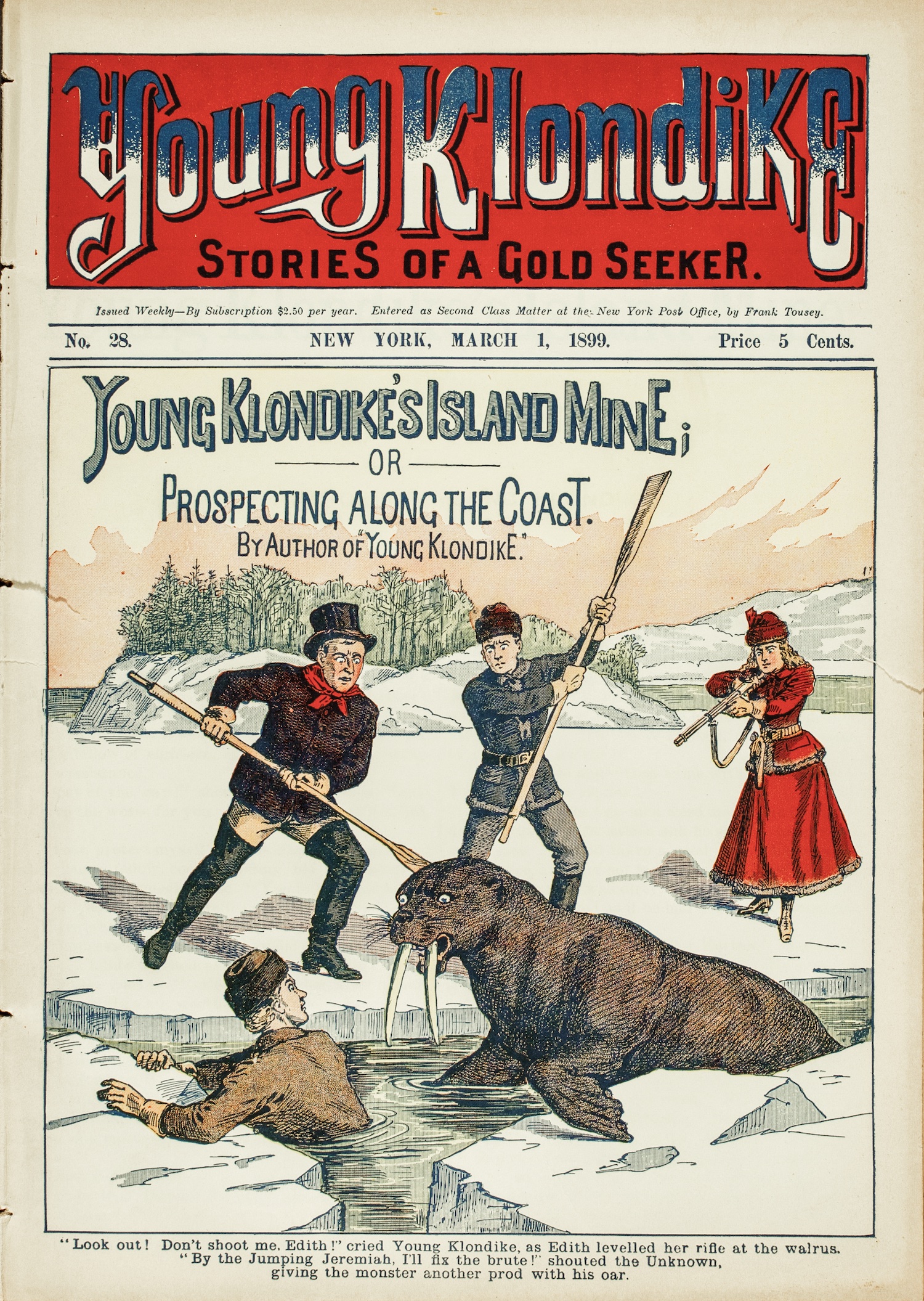

It sounds like a story from Jack London or Jon Krakauer: In 1966, two men traveled down the Yukon River in Alaska by canoe to recover papers from abandoned cabins. Paul McCarthy and H. Theodore “Ted” Ryberg were concerned that the generation of former gold miners who came to Alaska in the late 19th century were dying off, and they wanted to preserve that piece of Alaska history. Those explorations would prove pivotal to the Alaska and Polar Regions Collections & Archives formally founded by McCarthy in 1965 at the Elmer E. Rasmuson Library at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Since its founding in 1984, the University of Mississippi’s Blues Archive has collected virtually everything related to the Blues, from sheet music, concert tickets, and recordings to record label business files and even clothing. Thanks to a website revamp and a multiyear grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) to digitize materials, this year the archive is starting its 40th anniversary in style.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing