Among the Stars: The Adler Planetarium Collection | Archives Deep Dive

Chicago’s Adler Planetarium, which opened on May 12, 1930, is the oldest planetarium in the Western Hemisphere, and holds one of the largest collections of historic scientific instruments in the world, as well as rare books, manuscripts, archival materials, models, and photographs. Max Adler, the institution’s namesake, purchased and donated the initial collection of instruments, which included sundials, astrolabes, telescopes, and a projector.

|

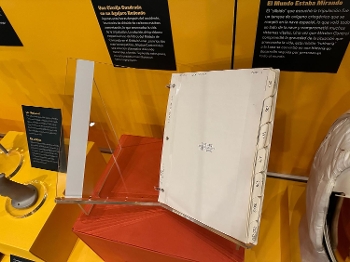

The cover of the malfunction procedures manual for the command module of Apollo 13 was torn off and used to make a scrubber, which converted carbon dioxide into oxygen, allowing the crew to breathe safely for the rest of the aborted flight. The caricature on the manual is of Jack Swigert, who was partially responsible for the development of the manual.Courtesy of the Alder Planetarium |

Books missing their front covers are rarely noteworthy or collectable. But the Adler Planetarium’s Research Center and Archives holds what is likely one of the most famous coverless books: the Apollo 13 CSM malfunction manual—yes, the Apollo 13 mission that was made into the popular 1995 movie starring Tom Hanks. The manual’s cover was used as part of a makeshift carbon dioxide scrubber, built to capture carbon dioxide and turn it into oxygen after an explosion in the command module (other components of the emergency construction included duct tape and tube socks).

This manual is one of many treasures held at Chicago’s Adler Planetarium. The Adler, which opened on May 12, 1930, is the oldest planetarium in the Western Hemisphere, and holds one of the largest collections of historic scientific instruments in the world, as well as rare books, manuscripts, archival materials, models, and photographs. Max Adler, the institution’s namesake, purchased and donated the initial collection of instruments, which included sundials, astrolabes, telescopes, and a projector.

In 1962, Roderick S. Webster and Marjorie K. Webster became the collection’s first curators on a volunteer basis; they donated their own rare books and artifacts to the Adler as well. From 2006–18, the archive was called the Webster Institute of History of Astronomy in their honor. It is currently known as the Adler Collections.

The first inventories of the archives were made in the 1990s. Various staff members, including Assistant Curator Jodi Lacy, Librarian Jill Postma, and Adler interns and volunteers helped compile the first archival finding aids in 2005. Over the past few decades, the Adler acquired papers from associates such as Maude Bennot, who served as the Adler’s second director (and was the world’s first woman to lead a planetarium), as well as notable figures including James Lovell—one of the first three astronauts to fly to and orbit the Moon—and astronomer Derek Price (1922–83).

During a recent renovation, the collection was measured at approximately 300 cubic feet, including 35,000–40,000 photographs. The library contains more than 6,000 contemporary titles and another 2,500 rare books, and the object collection holds 3,000 artifacts.

ONE SMALL STEP

While humans have always been interested in the sky above them, the Adler Collections give insight into modern understanding of the cosmos through the story of the planetarium itself. “Our history is very tied to the history of how we’re looking at outer space and how we’re educating the public,” explained Adler Librarian and Archivist Jane Kanter. The archives, she says, offer a combination of Chicago history, U.S. history, and the history of science.

The archive’s oldest item, a bound manuscript of Joannes de Sacrobosco’s treatises Algorismus, Tractatus de Sphaera, and Computus Lunaris , dates to the 13th century. Thanks to Max Adler’s acquisition of Dutch antiquities dealer Anton W.M. Mensing’s collection of more than 500 instruments in 1930, the archives are particularly strong on items from the 17th to 19th centuries.

While the collection holds a broad range of objects, books, and ephemera, Kanter noted that much of the focus is on items from Europe and the Middle East. She would like to see better representation of global cosmology and the study of constellations throughout the world, including Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. But it is always a balancing act, she said, for a small collection to attract researchers and focus on their strengths while also educating the public.

|

Sundial: Cannon, c. 1800, produced in France.Courtesy of the Alder Planetarium |

The objects collection has many sundials, including several cannon sundials—a device that has “a tiny cannon attached to it,” Kanter explained. “There is a lens that would catch the sun and light a fuse at exactly noon”—an early version of the alarm clock. Pocket sundials were intended for travelers who may have used them to tell time while on pilgrimage; coordinates of different locations showed users how to position the sundial so that it would work correctly.

The collection also includes a number of astrolabes, astronomical instruments used to make measurements of the skies. Some are quite fancy, made to be shown off in a library or study, Kanter said. Others were made to be used on voyages, often from durable, dense metal. Kanter described one Portuguese astrolabe made in 1616, recovered from the Spanish ship Nuestra Señora de Atocha that was sunk near the Marquesas Keys, off the coast of what is now Florida, in 1622.

More recent acquisitions include a collection of photographs from an Adler-hosted lens making workshop that began in 1936 as an “amateur telescope making space,” according to Curator Dr. Katie Boyce-Jacino, and ran until 1999. It was quite popular in the late 1950s and 1960s, she added.

The archives are on the lookout for objects and books representative of history of astronomy, Kanter added. As noted, the collection contains many astrolabes made for wealthy owners, but astronomical instruments were also made from cheaper materials such as wood and paper for ordinary people. The drawback for archival collections is that these materials were not as durable, and often were not saved, so they are more challenging to find.

Kanter is fond of Nathaniel Bowditch’s 1836 edition of The New American Practical Navigator, which was the go-to navigation guide of its day; often it was the only book on board a ship, “So people used it for writing poetry, writing notes about the weather, making little doodles in the margins,” she said. “Someone at some point made a cover for it from a sailcloth, which is still on it.” She pointed out the relatively short time between the 19th-century sailing guide and the Apollo 13 manual, noting how swiftly technology moves.

TO BOLDLY GO

The Adler has published books highlighting parts of the collection, including Sara J. Schechner’s Time of Our Lives: Sundials of The Adler Planetarium (2019) and Jodi Lacy’s Mapping the Universe (2007). Editor Michael J. Crow and associate editors David R. Dyck and James R. Kevin’s Calendar of the Correspondence of Sir John Herschel (1998) became a website.

Various digitization projects using the Adler archives include the Chicago Collections Consortium, an organization of Chicago cultural institutions that share resources, and Google Arts & Culture.

Students make use of the Adler’s collections as well. This past fall, a student from Bowling Green State University studying the history of music used in planetarium shows made use of the Adler’s audio from the 1970s and 1980s. The astronomy club from Northwestern University and Earlham College’s Kenlee Ray Library and Archives Fellows recently toured of the collection.

Other institutions have borrowed items from the collection such as a Chinese Star Map for Boston University’s Heaven and Earth: The Blue Maps of China exhibition, on view at Boston Public library’'s Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center. One of the Adler’s compasses is currently at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma (Central National Library of Rome) for an exhibit, “L’Ombra del filosofo: Giordano Bruno, Fabrizio Mordente, e le operazioni del compasso di proporzione” (“The Shadow of Philosophy: Giordano Bruno, Fabrizio Mordente, and the Operation of the Proportional Compass”).

Archives can be viewed by appointment only; message astrohistory@adlerplanetarium.org, and check out the website for more details. Currently the collection and archivist offices are under renovation, so the collection itself is housed off-site and appointments will be unavailable for the next two months. Looking ahead, Kanter hopes to create a mini-exhibition of materials once the new space is open. In addition, she wants to continue digitizing items, including older manuscripts from the medieval and early modern periods, and conduct a full inventory of all audiovisual materials; some were digitized, but others may have been missed, and she worries about durability of materials such as magnetic tape and VHS.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!