Not Just Narcan

As America’s opioid crisis becomes a tragic new normal, libraries have stepped up in a variety of ways. While the role of library workers—as first responders, training staff to save lives by administering Narcan to patrons who overdose in the library—has understandably received the most mainstream media attention, library responses are deeper and more proactive than that emergency intervention.

America’s opioid crisis forces U.S. public libraries to take a proactive approach to reduce stigma and harm

As America’s opioid crisis becomes a tragic new normal, libraries have stepped up in a variety of ways. While the role of library workers—as first responders, training staff to save lives by administering Narcan to patrons who overdose in the library—has understandably received the most mainstream media attention, library responses are deeper and more proactive than that emergency intervention.

As America’s opioid crisis becomes a tragic new normal, libraries have stepped up in a variety of ways. While the role of library workers—as first responders, training staff to save lives by administering Narcan to patrons who overdose in the library—has understandably received the most mainstream media attention, library responses are deeper and more proactive than that emergency intervention.

While public libraries have been reacting to the opioid crisis for roughly the past six years, the problem stems from as far back as the 1990s and a boom in prescriptions for pain relievers. By 2010, as prescription opioids became difficult to acquire, heroin and synthetic opioids such as fentanyl grew more prevalent. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), from 1999 to 2017, over 700,000 people died from drug overdoses. The CDC estimates 130 people die from an opioid overdose every day.

As the crisis shows no sign of abating, libraries are moving beyond emergency response to harm-reduction measures such as increased security, installing blue lights in public bathrooms, and providing information and resources. Whole-community, family-focused steps are being developed to address the epidemic’s wider impact and bring compassion—as well as potential early intervention—to the ways libraries help all those affected.

LIBRARIANS AS FIRST RESPONDERS

At the McPherson Branch of the Free Library of Philadelphia (FLP), adult/teen librarian Chera Kowalski began administering Narcan in 2017, after drug use in and around the branch became so prolific it dictated the rhythm of the day. Narcan, a brand name for naloxone, is a medication that blocks opioid receptor sites and reverses overdoses by opioids such as heroin, morphine, and oxycodone. It can be administered by intranasal spray or intramuscular, subcutaneous, or intravenous injection. Kowalski has used the intranasal spray multiple times.

“People were reluctant to allow their children to go to the library because people were shooting up on its front steps, and drug transactions were taking place openly,” explains Kowalski, a 2018 LJ Mover & Shaker (M&S). While heroin had always been available in the area, there was a sharp increase in 2016 spurred by an influx of drug “tourists” who came from elsewhere to obtain their fix. Among responding to overdoses, monitoring the public bathrooms, and dealing with intoxicated patrons, there was little time to do the work of running the library. The branch had always been a gathering spot for kids, but their exposure to people using illicit drugs began manifesting in behavioral issues.

Liz Sollis, marketing and communications manager, Salt Lake County Library (SLCL), partnered with the Salt Lake County Health Department, the University of Utah, Utah Naloxone, and Use Only as Directed, a public information campaign. The work has allowed SLCL not only to offer Narcan training to all of its staff and provide Narcan at each of its locations but also offer naloxone kits to the community since June 2018. “Each kit has a plastic bag, then a temperature-controlled bag with the naloxone and syringes, and an instruction sheet,” explains Sollis. The kits have been popular and are limited to two per person (although Sollis says the library is flexible on that guideline); 1,300 kits were distributed in the first six months.

The library will measure the impact of the program by tracking the number of overdose deaths in the areas where kits are distributed. While it’s too soon to have aggregated much data, Sollis said a Lyft driver came to the library to get a kit after someone overdosed in their car. She sees the program as being part of a focus on health.

|

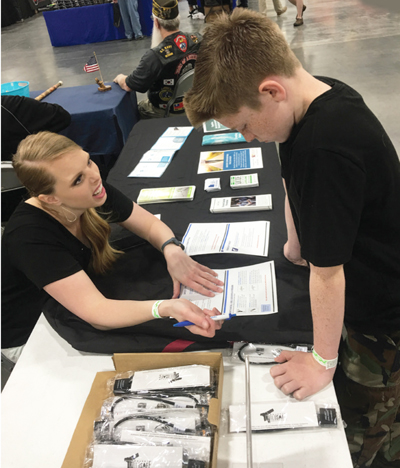

STAYING PREPARED Representativies from the Salt Lake County Library handed out naloxone rescue kits and gun locks at the Crossroads of the West Gun Show in Sandy, UT. In total, 100 naloxone kits and 143 locks were distributed.Photo by Jamie Chipman, Salt Lake County Library |

EXPANDING IMPACT

Although FLP’s Kowalski has saved numerous lives by administering Narcan, she says its use is not a solution. “Are we willing to refer people to mental health services?” she asks. “Are we willing to serve them in a humane and helpful way when they come through the door?”

Michelle Jeske, Denver Public Library (DPL) city librarian and a 2005 M&S, would respond with a resounding yes. DPL employees began administering Narcan in 2017 after a patron died of an overdose. Two years prior, Jeske hired the first social worker for the library, Elissa Hardy, who heads up the library’s Community Resource Team (CRT). “We have been trying to change the narrative,” explains Jeske. “A lot of people don’t understand that this is an illness. No one wants to be an addict.”

The CRT and security staff have been trained to administer Narcan and have reversed 25 overdoses since February 2017. But the focus has shifted from identifying problematic people to addressing behavior—a result, says Jeske, of work done by Hardy and the team. “We take a harm-reduction approach and meet people where they are, building relationships from which people can begin the healing process,” explains Hardy, who points to partnerships with community organizations as key. Looking beyond the library builds collective impact, explains Jeske.

Framing the opioid epidemic as a health crisis allows for a human-centered approach. Many libraries not only train staff to administer Narcan, they hold a wide range of programming to educate the public about how to identify and respond to people in crisis. Politicians, in turn, are creating legislation supporting the use of Narcan in libraries. In 2017, Congressman Sean Maloney (NY-18) proposed the Lifesaving Librarians Act (H.R. 4259). This legislation directs the Secretary of Health and Human Services to provide grants for public libraries in high-intensity drug trafficking areas (HIDTAs) to purchase naloxone rescue kits and/or provide training to enable staff to use them. Maloney’s proposed legislation was referred to the Subcommittee on Health in November 2017, where it remains. In Michigan, legislation was introduced in the State House in March 2019 to allow public libraries to purchase and train employees in administering overdose-reversal medication while protecting them from legal liability. Other politicians have joined community conversations and advocate locally and regionally, recognizing the importance of the work being done by public librarians.

BATTLE IN THE BATHROOM

“Due to cuts in funding for social programs, criminalization of drug use, and rising costs in housing, libraries are often the last place people can go,” notes Hardy. As easily accessible public places, library bathrooms have become ground zero in the opioid crisis. At one point, DPL reduced the number of bathrooms available to the public to make them easier to monitor. Other libraries have instituted such measures as routine bathroom patrols by security officers, monitoring bathrooms and checking in with users after five minutes, requiring an ID to use the bathroom, and even, in the case of the Spokane Public Library, installing blue lights, which allegedly make it more difficult for intravenous drug users to find a vein. However, this is potentially dangerous, since a 2013 study led by Alexis Crabtree, public health resident physician, University of British Columbia, found that not only would blue lights not stop most addicts from attempting to inject themselves but that the consequences of trying under those conditions include vein damage and infection.

Many libraries, including FLP, DPL, and the Boston Public Library, provide sharps disposal, where people can safely discard syringes. Hardy is quick to point out that rather than encourage drug use, making sharps disposal accessible reduces harm to others and means fewer syringes are discarded elsewhere on the property. It’s also of value for diabetics, who may use sharps to administer insulin or check blood sugar, and others with medical needs.

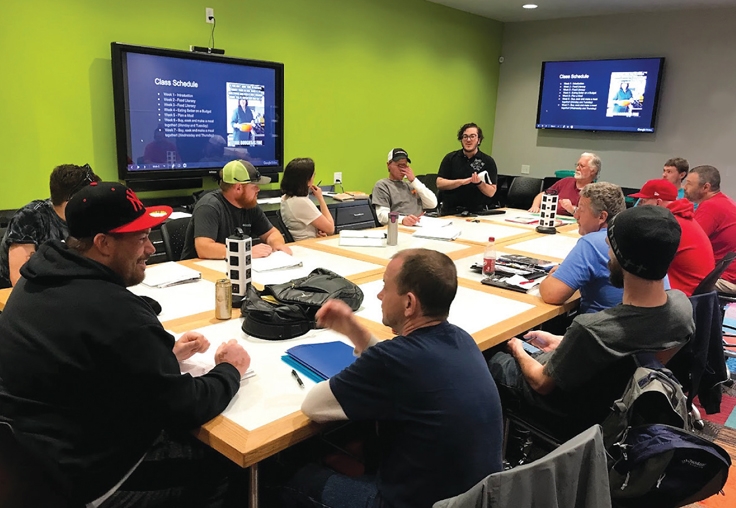

BUILDING SKILLS Ari Baker (standing), educational services manager at Blount County Public Library (BCPL), Maryville, TN, leads a Nutrition Module class at BCPL’s learning lab in partnership with Blount County Recovery Court as part of the Life Skills Curriculum.

Photo by Janna Federer

COMPASSIONATE PRACTICE

When K.C. Williams, director of the Blount County Public Library (BCPL), Maryville, TN, attended a public meeting in 2015 and happened to sit next to Stephanie Monday, a Blount County Recovery Court (BCRC) counselor, a discussion about community challenges led to what Williams describes as a “creative collision,” the Life Skills Curriculum. “Blount County is bisected by three major interstates, so it’s a natural route for drugs coming in and out of the area,” explains Williams. The result, say Williams and Ari Baker, BCPL educational services manager, is that the opioid crisis permeates every corner of the community.

“Everyone has a story of a family member or friend who has experienced addiction, and sometimes [people] tend to think that it’s a moral failing,” says Baker. “Instead, we look at it as an opportunity to provide the education and support to keep people out of prison.” The partnership with BCRC, an alternative sentencing program for nonviolent offenders with a history of drug and alcohol abuse, does just that. The 15-month curriculum builds life skills on everything from communication and finance to nutrition, career development, and much more. The biggest impact of the program, report both Williams and Baker, are the relationships built between the library staff and the students.

The importance of social connections is at the heart of the Grandparent Project, organized by Andrea Francis, manager of the West Toledo Branch of the Toledo Lucas County Public Library and a 2019 M&S. The Grandparent Project, a series of programs designed to meet the needs of seniors who are caregivers for children, began at the local community center in 2014. When Francis joined the community center board in 2016, she saw the potential to expand into the library. The program addresses four components: legal information; education; emotions and behaviors; and a resource fair. Through the classes and resource fair, seniors can find information while building a supportive community, and as Francis points out, “We have to acknowledge that [the opioid crisis] is impacting a large part of our community.”

Since launching the program, Francis has expanded it to create a Grandparents Club, a monthly informal meet-up for seniors to address their loneliness and isolation. “Their friends aren’t raising grandchildren,” says Francis, “and there is still shame and grief around the issue.”

Francis echoes what FLP’s Kowalski mentioned when talking about how exposure to drug use affects children and views disruptive behavior as an opportunity for intervention and discussion. DPL’s Hardy suggests that all libraries should include trauma-informed training with staff to understand better people who have or are experiencing trauma. She urges libraries to reach out to harm-reduction and treatment agencies to provide debriefing training and support to librarians who administer Narcan.

IT TAKES A VILLAGE

As libraries continue to grapple with a wide range of social issues, resources are being developed to support their efforts. The Public Library Association (PLA) and OCLC, supported by a $249,714 National Leadership Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, joined in 2018 to aggregate and distribute information and resources for libraries affected by opioid use. As part of the initiative, eight in-depth case studies are being created to show how communities of varying sizes are addressing the issue. According to Kendra Morgan, senior program manager at OCLC and WebJunction, other resources include a white paper, a series of webinars, and a Facebook group, Libraries and the Opioid Crisis. A steering committee composed of a group of librarians, including many mentioned in this article, are working with PLA and OCLC to provide input and guide the work. [For collection resources on the opioid epidemic, see “Out of Control,” p. 41-43.]

Collaboration—on the local, regional, and national level—is key to addressing the issue. The New York State Library convened a group of stakeholders, including the State Education Department, the State Department of Health, the New York Library Association, the Public Library System Directors Organization, and the Harm Reduction Coalition, to create Guidance for Implementing Opioid Overdose Prevention Measures in Public Libraries (nysl.nysed.gov/libdev/opioid/guidance.htm) to assist libraries in creating opioid overdose prevention programs. The Ohio Opioid Education Alliance brought together the Columbus Metropolitan Library; Alcohol, Drug and Mental Health Board of Franklin County; and other businesses and civic and community entities to launch a media campaign, “Denial, Ohio,” to identify and publicize the risks of opioids to children, families, and communities.

Anna Souannavong, assistant director of the Gates Public Library, NY, gathered stakeholders in January 2019 to host a series of community forums to educate the public. Speakers included medical professionals, law enforcement officials, and advocates from the addiction community. As a result of those conversations, the Gates to Recovery program was created, providing a drop-in referral center at the Gates Town Hall for those looking for help with addiction.

Morgan’s concern about focusing on partnerships is that it may leave out small, rural libraries where there are fewer resources, which may limit their capacity. But Betsy Kennedy, director of the Cazenovia Public Library, serving 6,500 people in Madison County, NY, offers an easily implemented model for smaller-scale collaborations. A former medic with the ambulance corps, Kennedy already knew about Narcan and its potential. Even before New York State developed its wider initiatives, she began having staff trained on how to use it and making it available at the library. “We are also working with a county agency to offer Narcan training to the general public at the library,” says Kennedy.

HUMAN-CENTERED RESPONSE

Public libraries have long created space and provided resources for people who are struggling, balancing compassion with practicality. The current response to the opioid crisis is an extension of what libraries already do—meet people where they are and help them address life challenges. Education and support programs help erase the stigma associated with addiction while building empathy for those affected. The crucial element, says Hardy, is to identify and connect people with community resources. “Libraries are being called to action, and they must answer,” says Hardy. “It’s essential that we don’t continue to push marginalized community members out. The library is for everyone.”

Erica Freudenberger is Outreach Consultant, Southern Adirondack Library System, Saratoga Springs, NY, and a 2016 LJ Mover & Shaker

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!