The Current Landscape of Horror Fiction: An Interview with Usman Malik

LJ Horror columnist Becky Spratford interviews Usman T. Malik, author of Midnight Doorways: Fables from Pakistan. She writes “his talent is blinding and his trajectory reminds me of Stephen Graham Jones, who I also found, like Usman, in Ellen Datlow collections first.” They discuss his work, influences, and the current landscape of horror fiction.

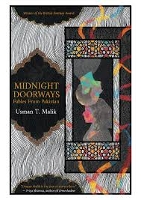

Usman T. Malik, winner of the Bram Stoker and the British Fantasy awards and a two-time Nebula nominee, is a Pakistani American writer and doctor whose name American audiences need to know. His fiction has been reprinted in several year’s best anthologies, and his debut collection, Midnight Doorways: Fables from Pakistan (KITAB), has garnered praise from writers such as Paul Tremblay, S.A. Chakraborty, Ken Liu, and Joe Hill. In her starred review, LJ Horror columnist Becky Spratford writes that “his talent is blinding and his trajectory reminds me of Stephen Graham Jones, who I also found, like Usman, in Ellen Datlow collections first.” She recently had the chance to email with Malik about his work, influences, and the current landscape of horror fiction.

Usman T. Malik, winner of the Bram Stoker and the British Fantasy awards and a two-time Nebula nominee, is a Pakistani American writer and doctor whose name American audiences need to know. His fiction has been reprinted in several year’s best anthologies, and his debut collection, Midnight Doorways: Fables from Pakistan (KITAB), has garnered praise from writers such as Paul Tremblay, S.A. Chakraborty, Ken Liu, and Joe Hill. In her starred review, LJ Horror columnist Becky Spratford writes that “his talent is blinding and his trajectory reminds me of Stephen Graham Jones, who I also found, like Usman, in Ellen Datlow collections first.” She recently had the chance to email with Malik about his work, influences, and the current landscape of horror fiction.

The following conversation has been slightly edited for length.

BS: What is it about horror, and specifically the short story form, that excites you as a creator and a reader?

UM: I’ve been gravitating to uncanny literature since I was a child. I remember watching a Bollywood horror movie as a five-year-old. The terror and awe stayed with me for years. Perhaps it was a jolting realization that I, too, was mortal, dispensable. As I grew older, I realized horror fiction and film woke me up in a way other genres didn’t; it has a sense of dark wonder and beauty that can pry open one’s brain in a different way. Horror can be more human and, paradoxically, more real than realism sometimes may be.

A short story spins and condenses fear in a way novels often can’t. The rise and swoop of the short form makes the eventual punch that much more powerful. That may be exemplified by the fact that otherwise decent horror novels fail their endings more frequently than good horror stories do.

Let’s talk about your most recent release, your first collection. You are not only presenting eight of your own stories, or fables, as you call them, but also black-and-white illustrations by different Pakistani artists.

As a child, some of my favorite books were illustrated editions of Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and other canonical writers. These books boasted sketch art and color plates by artists like Arthur Rackham, Harry Clarke, Edward Gorey, and Gustave Doré. I loved their fierce and evocative imagery; in some ways it made the fiction more tangible, more real. When the time came to put out my debut collection, I wanted my stories dramatized in a similar fashion, yet I wanted them done my way. These were stories of people who looked like me and acted like me; why should any visual representation of their inner or outer landscapes be any different? We reached out to nine Pakistani artists and designers whose collaboration has meant that the collection has sort of become a community project showcasing the best of Pakistani speculative art.

Who are the non-American or British creators who have most influenced you? Those you wish more American readers had access to.

I grew up grounded in Urdu literature. Writers of pulp fiction and what we might call middle-grade or YA fantasy, horror, and spy stories such as Mazhar Kaleem, Maqbool Jahangir, the great A. Hameed (who also penned the most popular Pakistani TV series for kids called Ainak Wala Jin), Ishtiaq Ahmad, all heavily influenced and perhaps shaped my reading preferences as a child. I also read and listened to a lot of Urdu poetry, sung or recited on TV or radio. Naiyer Masud is perhaps the most important post-Partition Urdu writer of the short story. His work runs in the vein of Kafka and occasionally Thomas Ligotti, yet the minimalist, almost Hemingway-stringent style of his prose lends it an unparalleled uncanniness. It is criminal that he is not better known to the masses in the Indian subcontinent, let alone in the West.

You are a dual citizen, American and Pakistani and live in both places. You are also a medical doctor who writes speculative fiction. These dualities define you as a human, but how do they manifest themselves in your work?

Dualities and forking paths have pretty much defined my career trajectory. Had it not been for my brother's visit to Florida from Pakistan in 2012, I'd have remained a physician who never took up the pen; his leaving prompted a fit of homesickness that made me desperate to do more than medical work, which was burning me out. Had I not decided to fly off to the World Horror Convention in Salt Lake City, a con I'd never even heard of till three days before the con weekend, I'd never have met up with other writers of uncanny or horror fiction. The SF critic John Clute once told me migration is self-exile. It was a startling statement that has reverberated in my head and my fiction to this day. I've never truly felt at home in either Pakistan or the US since I moved to the States more than a decade ago. That nearly umbilical severing led to heartache, nostalgia, and a deep sense of loss for me that I had difficulty coming to terms with for years. Later that feeling of being unrooted got compounded by the fact that I could neither devote myself entirely to writing nor could I become A. Rae Gilchrist's 'compleat physician'; I was compelled to be both by forces beyond my control. I do think that duality has seeped into most of my work. My characters are often consumed by seeking. Several of my stories, as Brian Keene pointed out to me once, are often about real or imagined childhoods. Overtime, I have learned to pick the best of both worlds: medicine and literature; Pakistan and America. And while I hope that that might bring a sense of grounding to my work, I hope it does not lead to absolute stasis.

You recently had a novella released through Tor.com too. Can you tell us about that tale, and also how you approach that format differently from a story?

I rarely plan for a story to be a novelette or a novella. There are certain things I want to do in a new story, perhaps an interesting concept, a particular image, voice, or narrative structure, and I follow through on that. Some ideas need less space, others more. This particular piece, City of Red Midnight: A Hikayat, is a feminist retelling of an Arabian Nights story. I wanted to structure it like a tale from A Thousand and One Nights with stories unfurling into more stories, the layers of fantasy suctioning the reader deep into a labyrinth of interconnected fantasies till it all coalesces and blossoms together. Doing that required a bit more space, so it became a novelette.

Why do you think horror is so popular right now?

Horror is always in vogue; readers and viewers just don’t accept it under that moniker all the time. From 1995 to 2010 or so, it was sold to the mainstream under various genre umbrellas. From Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006) to Justin Cronin’s The Passage (2010), a mass audience loved and consumed horror under various guises. Meanwhile, excellent horror kept thriving in the small presses, and writers such as Paul Tremblay, Gemma Files, Stephen Graham Jones, Tanith Lee, and Jeff VanderMeer continued to churn out excellent horror fiction. Over time, because they were brilliant, several of them “broke through” and that along with the success of newer writers helped horror re-accrue the respect and wide acceptance it enjoys today. As to why it’s especially popular right now, our current sociopolitical environment isn’t cozy, to say the least, and horror, as a genre, is very good at crystallization of contemporary anxieties. Its symbols and metaphors allow us to capture the zeitgeist in tangible terms. Horror fiction and filmography allow the channeling of national and personal uncertainty into drawable, often subversive conclusions. That is no mean feat.

Becky Spratford is a readers’ advisory (RA) specialist in northern Illinois and the author of The Readers’ Advisory Guide to Horror (2d ed., ALA). She runs the popular blogs raforall.blogspot.com and raforallhorror.blogspot.com. Readers can connect with her on Twitter @RAforAll.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!