The Library Is In

Nearly nine out of ten adults have difficulty using health information, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This isn’t surprising—thanks to the open access movement, there are a plethora of reliable medical sources out there, but many are not written for a lay audience. Meanwhile, drug companies on the one hand and anti–traditional medicine advocates on the other flood the Internet with authoritative-sounding contradictory material. People who are scared about a possible serious medical condition are not in an ideal mind-set to winnow and retain a lot of new data, especially if the process itself is new to them. Rushed doctors don’t always have time to explain context fully to their patients, and patients are often too intimidated to ask. That’s assuming the patron even has a doctor—even after the Affordable Healthcare Act (AHA), many patrons can’t afford treatment, or need the library to help figure out whether they need medical help and how to get it.

In fact, the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Philadelphia Research Initiative determined that “more than a third (34 percent) of all people who came to the library were looking for health information,” according to Free Library of Philadelphia (FLP) strategy coordinator Autumn McClintock. Although the first rush of education around how to sign up for AHA coverage is past, changing life circumstances will still mean new patrons looking for assistance over the long haul. Health literacy is therefore a core public library service—and some inventive libraries are going beyond literacy to help patrons improve their well-being directly.

GET WELL HERE Library health services span a wide range of sizes and approaches. Top: Pima Cty. Health Department library nurse Barbara Oppenheimer gives a patron a shot at the Wheeler Taft Abbett Sr. Branch.

Bottom: at Pima’s Valencia Branch, nurse Mary Frances Bruckmeier (l.) discusses health care.

Photos courtesy of the Pima County PL

Nurses in the library

In 2012, Arizona’s Pima County Public Library (PCPL), Tucson, added a new employee to its payroll: a registered nurse. Today, one nurse is employed by the library and stationed at the Joel D. Valdez Main Library; ten others, who work for the Pima County Health Department, visit 11 of the 27 branches in the system at least once a month. PCPL serves a population of 996,554 and had 5.6 million visitors in FY14/15.

“Care is open to patrons of all ages who are open to receiving care but specifically targets the homeless, unsupervised adults with substance abuse and poor health, children and elders who’ve been abandoned, or those with behavioral problems or mental illness,” explains Holly Schaffer, the library’s community relations manager. Nurses offer everything from case management to blood pressure screenings.

Library nurses can have a tremendous impact, as Schaffer illustrates with this story about former PCPL nurse Daniel Lopez, RN: Lopez “was referred to a patient who was suffering from urethral pain. The man—homeless, unemployed, and lacking health insurance—had received an indwelling catheter and leg bag at a local hospital. After consulting with the man, Daniel learned that the hospital had been aware of the patient’s diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer but chose to turn him away.”

Lopez “addressed the patient’s basic needs, including helping him to find shelter in a transitional housing program. Shortly thereafter, the man was approved for housing, sold his vehicle, and moved into his new residence. Daniel also assisted him [in] navigat[ing] the complex health system, getting him an oncology appointment, which was covered once the man turned 65.”

Lopez’s efforts didn’t end there: “The man began treatment and was told he had six months to live, at which point [Lopez] helped him begin the long process of reconnecting with some of his estranged family members. Many months later, [Lopez] ran into him at the library, where the man informed him, ‘They say I had six months, but the treatment put the cancer to sleep.... If things keep working like this, I’ll have much longer than that.’ ”

In 2014, nurses made more than 400 visits to libraries, gave 190 presentations on health topics, had individual contact with close to 6,900 individuals, and performed 1,883 interventions such as Lopez’s—helping patrons find resources such as dentists, food banks, and therapists. “Great strides have been made to ensure that public health services are readily available for our most vulnerable customers, making sure that the library—and the community at large—care about their needs,” says Schaffer.

At FLP, for the past three years, nursing students from the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing have regularly offered presentations, blood pressure screenings, and community health fairs at two branches as part of their coursework. In 2015, 550 people attended 40 such programs. Now former student Melanie Mariano, BSN, will provide hands-on nursing care at the Parkway Central Branch for a year. Programming should start in October. (Mariano’s not the only health professional at the library; she joins two behavioral health specialists, contracted through the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual disAbility Services, who work at the library on a part-time basis.)

Collocation, collocation, collocation

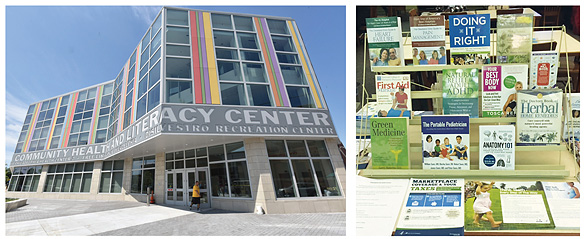

If “meet them where they are” is a core tenet of exceptional library service, there is more than one way to achieve that goal. In addition to bringing health care into the library, FLP is taking the whole library to health care. The library’s most recent health initiative is the South Philadelphia Community Health and Literacy Center. The collaboration, which opened in May 2016, consists of the South Philadelphia Library, a Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) pediatric primary care center, a Philadelphia Department of Public Health community health center, and the DiSilvestro Playground and Recreation Center. The South Philadelphia Library focuses on health literacy, and some staff will receive Consumer Health Information Specialization (CHIS) certification from the Medical Library Association. The one-stop shop will make it easy for families to get health care, stay active to promote wellness, and learn more about their health in one convenient package.

Salt Lake County Library Services (SLCLS) also provides library settings in other facilities—such as in clinics and hospitals. It has been able to reach more patrons, especially children, with this approach. The Byington Reading Room is located in a medical building that also houses two pediatric clinics, including a WIC (Women Infants and Children) center affiliated with the Salt Lake County Health Department. “The room serves the clinic’s clients, allowing each child who visits to select a free book of their own,” according to James D. Cooper, SLCLS director. The Reading Room is staffed by two part-time librarians and gives away an average of 80–100 books a month. (The nearby Primary Children’s Hospital also distributes books.)

The reading room has been so successful that in 2015, “The county health department asked us to expand the model to the other clinics in the valley serving WIC clients,” Cooper says. Currently, three libraries are working with local WIC clinics. “We are averaging [giving away] 1,000 books at all three clinics in a quarter. In addition, library staff provide early literacy workshops to clinic [workers].”

Since 2014, librarians have visited Primary Children’s Hospital several times a month to provide story time to youngsters in long-term care. Patients can attend in person or view the event on a TV monitor (and call in to participate). Last year, 101 children attended; an additional 132 listened remotely. Local hospitals also play a role in the library’s new Books for Baby program, which distributes a bag containing a book in English or Spanish, as well as a welcome card and early literacy tips to the county’s youngest residents (and their parents).

The library is currently collaborating with local agencies on a new program that will provide welcome packs and board books to be disseminated to new families participating in the health department’s home visitation programs.

The Community Health Center, Free Library of Philadelphia, displays a wealth of health materials.

Photos courtesy of the Free Library of Philadelphia

Outreach and input

At East Brunswick Public Library (EBPL), NJ, the community of 48,000 was rapidly changing. As information services manager Karen Parry explains, “East Brunswick was transforming into a patchwork of immigrant [communities] from Egypt, India, China, Iran, Russia, Pakistan, Philippines, and Korea.... Immigrants had a pressing need for medical care and turned to the library for assistance. Librarians regularly provided articles about diagnoses that were easy to read. They often were asked to help locate a doctor or dentist, preferably one who spoke their native language.” Meanwhile, a growing senior population was often uncomfortable navigating online information sources.

So in 2010, EBPL launched Just for the Health of It. Specially trained staff answer questions, help patrons access reliable consumer health information, and regularly perform outreach at two facilities affiliated with the local Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, which recognized Just for the Health of It as a model program in 2013. In 2015, Just for the Health of It served an estimated 3,000 patrons. The library also developed a senior-friendly, open source community web portal, wellinks.org, which provides links to vetted health information in the seven languages spoken in the community. It was visited 17,000 times last year.

None of this would have been possible without partnerships. Becoming an affiliate member of the National Network of Libraries of Medicine, Middle Atlantic Region (NN/LM MAR) in 2010 was particularly helpful, says Parry, who currently serves as chair of its Special Advisory Group on Consumer Health. “This partnership gave the library access to free specialized training and funding awards that would not have been possible as a stand-alone library.” NN/LM MAR has provided CHIS training and certification to five librarians as well as grants that enabled EBPL to design and later update wellinks.org.

Proactive and pro active

Crandon Public Library (CPL), WI, began expanding its health programming in 2011, when Director Michelle Gobert was invited to participate in the Forest County Health Department’s five-year strategic planning session. “It was the first time I had heard about county health rankings and the different scientific-based programming that was being done across the state to promote a healthier lifestyle,” she recalls. As a result, CPL’s efforts to promote wellness among the 6,054 people it serves emphasize nutrition and exercise. In 2013, the library, along with the health department and local nonprofit Forest County Ties That Bind Us, launched a running program, now called Community Kickstart. Seventy-four people registered for the nine-week training session, and about 50 percent completed a planned 5K run. The program was repeated—with even greater success—in 2015.

The library has also partnered with the health department on children’s programming: a Thanksgiving story hour featured a book about cranberries, an activity, and a demonstration on making a healthy cranberry salad by the Forest County Health Department director. Some 30–35 children and adults attended.

CPL also received a stipend from OCLC as part of its Health Happens in Libraries initiative, and, in May 2015, CPL produced Iron Chef—Healthy Fruits & Vegetables Edition with the help of the health department, Forest County Ties That Bind Us, Forest County Coalition on Activity and Nutrition (Forest County CAN!—CPL is a member), and the Crandon School District. The competition was held at a local school cafeteria, where 15 participants created healthy dishes.

Finally, this past spring the library again partnered with Forest County Ties That Bind Us for the organization’s Colors of Cancer run. The event raised more than $18,000 for the nonprofit, which then donated $3,000 to the library for use in youth programming.

“Partnering with our local health department on specific initiatives has made a huge impact within our community,” Gobert says. “The library is now seen as a community partner.… It has allowed us to be part of the conversation and therefore part of the solution.”

A Better Health Workshop at the Wilkes Cty. PL, NC; staff from the East Brunswick PL, NJ,

promote Just for the Health of It at a local farmers market.

Wilkes County photos courtesy of Wilkes County PL; East Brunswick photos courtesy of East Brunswick PL

Food for thought

At the Wilkes County Public Library (WCPL), North Wilkesboro, NC, the impetus for health programming stemmed from 2011 health rankings of counties statewide. “At that time, Wilkes ranked 69 out of 100,” County Librarian Julia Turpin explains. “I think there was a feeling that we could do better, and the library wanted to be a part of that.”

In spring 2011, WCPL, which serves 68,000, began offering its Health Luncheon Series. These information sessions run for three months and cover common conditions such as heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. Attendance at each session has reached 30, the maximum. In fact, “The series was so popular, we added an evening [session]; 31 people attended,” Turpin adds.

WCPL was also a recipient of an OCLC stipend, which resulted in the Stanford University–designed Better Choices, Better Health Workshop, a collaboration with the Wilkes County Health Department. The program, which ran for six weeks in 2015, helped ten individuals to manage chronic disease.

WCPL’s current health programming also includes a class on infant sleep safety for expectant mothers and infant caregivers. It, too, is a collaboration with the health department. The class regularly draws 20–25 attendees, and while it was originally scheduled for July 2016, like the luncheon series, it proved so popular that “we scheduled training sessions through the end of 2016.”

“By partnering with local agencies in the health-care field, we are able to offer these sorts of quality programs in the library, which for many may represent a less intimidating space than a health department or hospital,” Turpin points out.

TEAM EFFORT Partnering between patrons and staff improves health outcomes. The Crandon Public Library’s (CPL)

Ties That Bind Us Colors of Cancer 5K run (top); CPL’s Iron Chef Healthy Fruits & Vegetable Edition competition (bottom). You’re never too young to learn to cook well. Photos courtesy of Crandon PL

Health starts at home

Finally, not all library health programs are aimed at patrons. “Studies show that healthy, happy employees are more productive, take fewer sick days, and contribute to a positive atmosphere for staff and the public alike,” notes Allison Bies, fiction librarian at the three-branch Schaumburg Township District Library, which serves more than 134,000 residents in Illinois. The library’s Wellness Committee regularly offers programs to promote health among its 300-strong staffers.

A recent event featuring a professional organizer had 40 attendees. “The wellness programs are very informative,” says circulation assistant Petri Flowers. “I believe a person can never have too much information when it comes to health and wellness topics.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!