University of Maryland Online Punk Rock Exhibit Provides Accessible Information for Enthusiasts of All Levels

Punk rock music has lived many lives, but its spirit has always meant the freedom to question everything, and to create or think for yourself. So how does one take the heart of this movement and archive it? That’s a question curator John Davis and Ben Jackson, manager of the University of Maryland’s Michelle Smith Performing Arts Library, had to ask themselves while creating their online exhibit, Persistent Vision: The D.C. Punk Collections at the University of Maryland.

|

Punk rock music has lived many lives, but its spirit has always meant the freedom to question everything, and to create or think for yourself. So how does one take the heart of this movement and archive it? That’s a question John Davis and Ben Jackson, curator and manager, respectively, of the University of Maryland’s (UMD) Special Collections in Performing Arts (SCPA), had to ask themselves while creating their online exhibit, Persistent Vision: The D.C. Punk Collections at the University of Maryland. The name comes from the idea that punk rock music is persistent by nature, obstinately determined to endure and evolve as times continue to change. The archives were drawn from SCPA, held in the university's Michelle Smith Performing Arts Library, and while still a young exhibit, the plan is to only add more detail and expand their scope indefinitely.

Why Washington, DC? That’s where “the tight-knit community of punk rock musicians, zinemakers, photographers, and organizers have continually pushed the genre in new directions,” Jackson explained. “The subgenres of hardcore, post-hardcore, and emo, as well as the straight edge subculture of radical sobriety and the international feminist movement riot grrrl, all got their start or had significant parts of their foundation built in DC. All of this was possible because the DC scene emphasizes participation over consumption, using the do-it-yourself mentality as a means of challenging the mainstream music industry and its values.”

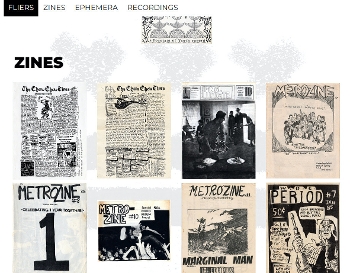

Given the DIY, outside-the-lines nature of the subject, “The idea was to create a digital platform for people to relate to our collection,” Jackson said. “For a long time, we had this group of flyers and zines, photographs and production materials, but there wasn’t an easy way to comprehensively browse through it.”

Usually, unless a researcher was searching for something detailed and specific, finding aids would be required to sift through the sheer amount of information available at the UMD collections. With Persistent Vision, however, Davis and Jackson aim to provide accessibility for those who have lived and experienced the DC punk rock scene firsthand, as well as those who are new to the movement or simply curious. This involved creating a holistic home for the collected materials, as well as a plan to contextualize them. It should be noted that finding aids are still available to use within the library’s collection, but are not used for the exhibit; the idea is to give more direct browsing options to both students and non-students.

The exhibit includes everything that has been digitized from UMD’s 15 individual collections on punk music that are held in UMD’s special collections. “As a performing arts archive,” Jackson said, “we hold collections of individuals and organizations donated for preservation and public access. SCPA initially began collecting on the DC punk scene nearly a decade ago to further this mission, and we have been working to digitize as much as possible of these collections.”

Formatted in a year-by-year structure from the 1970s to 1992, the digitized items range from audio clips of punk bands like Tiny Desk Unit performing live in 1979, to handwritten flyers for Capitol Crisis, to videos of record producer Skip Groff discussing the band Teen Idles during the ’80s. “If the materials relate specifically to the DC punk community,” Davis said, “they’re included.”

|

Persistent Vision page for 1985, highlighting fanzinesCredit: The D.C. Punk Collections at Special Collections in Performing Arts, University of Maryland Libraries |

How did Davis and Jackson decide that, and what were the criteria? Jackson continued, “This exhibit is trying to cast a wide net in terms of how one defines punk [and therefore what to include], because often rigid definitions of punk can change in just a few years.” It was essential to keep in mind that less storied bands weren’t less important. “We want to tell a broader, richer narrative of the scene,” he noted, “including the bands on the fringes.”

Davis has been involved in the punk music scene since the ’90s. He played in bands, published fanzines, ran a record label, and promoted shows, while Jackson considers himself more of an outsider who was first introduced to punk music through video games. Yet when it comes to understanding history and music, both seem acutely aware of a museum or library archive’s power to talk about and challenge pre-existing ideas of race, whitewashing, and gentrification.

“That should be, and for all of us was, at the center of mind in creating this [exhibit],” Jackson said. “My graduate work was in ethnomusicology, where my research was on musical communities and gentrification in Washington, DC. The punk scene in DC is generally one where women, people of color, and queer communities have always been involved in every aspect of it, and still when you see popular representations, you often think of angry young white men.” This does not mean pretending those men weren’t there, but acknowledging that those stories have been told—and that many more exist.

How does UMD use Persistent Vision to fill out the narrative, or tell the story of punk rock music, in a different way? Jackson continued, “What we came back to is letting our collection speak as a guiding point. We focus on the zines and quotations from members of the scene. And we use flyers of the shows as primary sources.” The bands Chalk Circle and Fire Party are two examples he mentioned—an all-woman punk band and the second including women of color. “We’ve tried to use this exhibit as a platform to focus on complicated narratives and bring to light what was already there, but was maybe less well-known.”

But why punk, and why now? To Jackson, it comes down to the timelessness of a movement that almost requires active engagement to exist. “One thing that engaged me about punk rock music is how the scene is almost defined by how much you participate in it,” said Jackson. “People at the concerts were also the people making zines, taking pictures, passing out flyers, organizing shows as benefits for different community organizations, and using punk as a platform to talk about political movements.”

If participation is key for the scene, then in order for Persistent Vision to represent punk, the collection needed to be users to engage with it. Flyers advertising Persistent Vision were placed around the UMD campus, but Davis and Jackson hope that the exhibit will reach a wider crowd. “We’d love to see people who are interested in history,” Jackson said, “and also graphic designers interested in punk rock flyers, or how people put a zine together. Maybe someone is starting a band and would like to know how punk rock bands engage with fans. Really, anything that inspires new performance and creation.” In addition to the flyers, Davis emphasized the importance of social media, specifically Instagram (@umdpunkcollections), for spreading the word.

One challenge for assembling this exhibit was time, with thousands of digitized items to include. So Davis and Jackson decided to let the exhibit evolve, as opposed to rushing to create a finished—and static—collection. “It’s an ongoing project,” Davis said, “with additional essays and more digitized materials to add, but we felt that the current state of the exhibit—covering the 1970s up through 1992—had a sufficient amount of materials to get people started. Hopefully, they will come back to see the materials we add in the months to come.”

Jackson and Davis, however, are also aware that their informal two-year timeline included a budget, and not all librarians or archivists have the same resources to put something like this together. “If anything, let this conversation serve as a reminder that we need more dedicated positions where people can spend their time doing more digital outreach,” Jackson said; he hopes libraries will continue to serve populations outside of their universities or regular patron base. “There are also so many archives that are on a shoestring budget with lone archivists,” Jackson pointed out, “and they’re asked to do so much already that it’s hard to say you should dedicate all your time to doing this. But if you’re not doing the outreach, then you spend all your time with those who only want the information for their dissertation or writing a monograph.”

Whether you’re a punk rock connoisseur, a PhD candidate, writing your first song, or hoping to learn about 1970’s design, Persistent Vision is now live—and don’t forget to revisit from time to time, as new information and details are added.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!