Public Programming with Virtual Murder Mysteries

Public libraries are seeing success with virtual murder mysteries, which vary in format from Zoom events to text-based games to videos.

Though physical access to the Elmhurst Public Library (EPL), IL, is still limited, the library, like many others, is seeing success with online programs that might once have been in-person. These include virtual murder mysteries, which vary in format from Zoom events to text-based games to videos.

At EPL, a Zoom event earlier this year saw attendees donning fedoras, solving puzzles, and questioning witnesses, all to figure out who “whacked” Jimmy the Legs. EPL hired Baig of Tricks Entertainment for a mafia-themed game set in 1928. A Baig of Tricks employee ran the game and played the role of an investigator; attendees played the suspects and were encouraged to display props and use speakeasy- or Twenties-themed backgrounds. The first game was so popular that EPL quickly scheduled a second, said Adult and Teen Programming Coordinator Jez Layman.

The Clearview Library District (CLD), Windsor, CO, also used games created by outside companies, though library staff ran the activities themselves. Adult Services Assistant Jason Boak noted, “Prep just entailed familiarizing myself with the game play sequence, studying the characters so I could help participants, and getting character info to those who registered to play.” He added, “Our adult services team is made up of just four people, most of whom are part-time, so selecting games with minimal prep was important.”

Costs tend to be relatively low. EPL paid Baig of Tricks $75 per program, while CLD paid $29.95 for a game from Playing with Murder, and $49.95 for a game from Keith & Margo’s Murder Mystery.

|

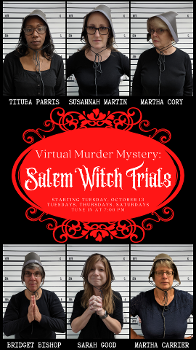

A flyer promoting the Wood Library's Salem Witch Trials virtual murdery mystery, created by Stephanie Toomey, volunteer coordinator and outreach services |

Other librarians have set up their own virtual murder mystery programs, which, though more time-consuming, can be satisfying for those eager to stretch their creative muscles. Alexis Lawrence, adult service librarian at Wood Library, Canandaigua, NY, wrote a game that blended her passion for true crime with a deep dive into history. Her program, which she launched last October with Stephanie Toomey, volunteer coordinator and outreach services, centers on the fictional murder of real-life historical figure Ann Putnam, who in 1692, along with several other young women, accused more than 60 Salem, MA, residents of witchcraft. “I did research into the trials and each character, and that’s how I came up with some of the scripts and ideas,” said Lawrence.

Lawrence filmed videos featuring characters such as Susannah Martin and Tituba Parris, played by library staffers. Toomey edited the videos with iMovie, incorporating sound effects, music, voiceover narration, and visual cues like lightning. Videos were posted three times a week to the library's Instagram and Facebook, allowing patrons to guess the identity of the murderer ahead of the reveal in the final installment.

At the Shaker Heights Public Library (SHPL), OH, Youth Services Associate Kristen Chilson and Youth Services Manager Shannon Fischer Titas posted YouTube videos in which investigators look into the murder of a beloved librarian. In the comments sections, patrons could “like” comments telling the detectives what to do next, such as investigate the crime scene or interrogate suspects.

Librarians should be aware that filming can be a lot of work. Chilson’s program took four months to launch: two months of script writing, two and a half months to film scenes, and a month to edit. While she tapped her colleagues for help (library staff played the role of characters in the videos; children’s librarians, experienced with iMovie from virtual story times, offered tips on editing), she took charge of the project, from writing the script to recording and editing videos, and advises others to delegate more than she did.

Lawrence said that filming took about one to three minutes per scene; she devoted roughly one to two days per video (nine videos were filmed in total). Sometimes reshoots were necessary, which added another couple days, and she suggests that librarians shoot as much video as possible up front, even if they don’t think they’ll use all of it. She added, “We used supplies that were already within the library, like white and black paper for hats, so no additional cost was incurred aside from time.” Chilson didn’t have any costs apart from time, either—she used an iPad, camera stand, and lightstand that the library already possessed.

Programs like those at the Wood Library and SHPL allow patrons to participate on their own time. “I didn’t want to restrict customers to playing at 3 p.m. on Monday, for instance,” said Jennifer Nandal, senior adult program specialist at the Harris County Public Library, Houston, TX, who last fall adapted an in-person murder mystery game into virtual format. “I kept thinking about adults like myself. I’d want to enjoy a glass of wine, some chocolate, and do this late at night while my daughter’s asleep.”

Nandal created a game in which participants respond to multiple choice questions as they investigate the murder of Dracula; images of clues help them crack the case. She used Google Forms because it gave her more options for uploading images than Microsoft Forms. She created witness statements and a police report with Publisher, and relied on Canva to make images of clues (such as a crumpled piece of paper with a woman’s name on it). She encourages librarians to try out Canva, which provides stock images, animation, and music. The program is easy for novices to use, and there’s a free version available, Nandal said. “You just have to be willing to explore.”

Asynchronous games also have the potential to reach more people over time. Though the videos for Wood Library’s event were posted in October 2020, people continue to view them months later, with several videos racking up more than 1,000 views.

Programs held at a specific time can pose challenges if patrons can’t commit to attending. Layman said that the first time her event took place, some people canceled after registering. “I kept moving people from the wait list, and I would stress, please only register if you know you are coming.” Having stepped in to play roles initially assigned to patrons who signed up but didn’t attend, she warns librarians to “be prepared to cover any characters if someone doesn’t show up.”

Still, scheduled virtual games offer patrons a much-needed chance for interaction. Layman has noticed that many are experiencing loneliness due to COVID, but “virtual events like this are a chance to connect, meet new people, and have some fun for a couple hours.” She added, “Virtual programming has taken some of the pressure off of people with social anxiety to attend events and having a character with a set script made it even easier for folks to ease into the group, which makes them more likely to come back for other programs.”

Though setting up a murder mystery program may sound daunting, librarians have a lot of latitude. Nandal stressed, “It’s really open to interpretation. You can make it as simple as you want or as complicated.”

|

An image from a virtual murder mystery game created by Kortni Springer, reference librarian and programming coordinator, Acorn Public Library District, IL |

Kortni Springer, reference librarian and programming coordinator at the Acorn Public Library District, Oak Forest, IL, created a game revolving around the murder of an author visiting a library. Participants read an overview of the murder, then are asked questions about what they want to do next (investigate the library, question suspects, etc.). She used Twine, which requires some knowledge of HTML, but she found it generally intuitive; when she encountered roadblocks, she turned to online tutorials.

Those seeking inspiration should consider taking part in other libraries’ virtual murder mystery programs. Layman noted, “I think that’s one of the real advantages of virtual programming, that we have a little more flexibility to do that because there’s no travel involved and we can participate from anywhere.”

Patron response has overall been positive. “We’ve found that murder mystery games attract a great mix of younger and older adults from our community,” said Boak.

“Just have fun with it,” said Nandal. “Creating online content for our adult audience has been really challenging, but I’ve found many of our successful programs are the ones I have the most fun creating.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!