Magic Words (and More): Magic and Illusion at UT Austin and the American Museum of Magic | Archives Deep Dive

Magic tricks may be momentary, but the annals of performance magic leave a record, commenting on and reflecting the political, cultural, social attitudes of their day. Two collections, the University of Texas at Austin Harry Ransom Center’s Magic and Illusion collection and the American Museum of Magic’s Archives and Library, hold a wealth of information about magic and performers, with a focus on the 19th and 20th centuries.

|

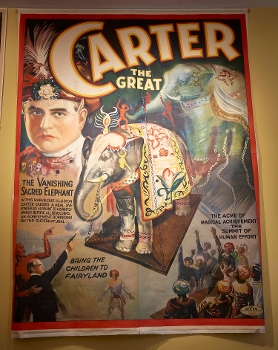

Carter the Great, Vanishing Sacred Elephant, by the Otis Lithograph Company, circa 1920Courtesy of AMM Archives and Library |

By definition, performance magic is ephemeral. A magician performs the trick on stage or in a club or lounge, sometimes making objects or people disappear, other times making things appear in unexpected places. Afterward, the magic trick is over, with only the audience’s sense of wonder and disbelief remaining. The tricks may be momentary, but the annals of performance magic leave a record, commenting on and reflecting the political, cultural, social attitudes of their day. More than simple entertainment, performed magic is an intersection of many disciplines, including applied psychology, mathematics, science, and writing skills.

Two collections, the University of Texas (UT) at Austin Harry Ransom Center’s Magic and Illusion collection and the American Museum of Magic’s Archives and Library (AMM), hold a wealth of information about magic and performers, with a focus on the 19th and 20th centuries.

“Performance does not exist in a vacuum,” said Eric Colleary, Harry Ransom curator of the performing arts at the University of Texas at Austin. “Theater, magic circus, vaudeville, dance, and opera are responding to what is happening in society broadly.” In the 19th century, he noted, spiritualism came into vogue as a response to major economic, technological, and cultural changes brought on by the industrial revolution. Magic, like spiritualism, resonated with audiences in celebrating the unseen worlds and questions about death, reflecting the anxieties, fears, and awe that U.S. audiences were facing as their everyday lives changed.

Magic’s reflection of society at large also replicated and furthered racial stereotyping—in particular, helping to underscore a racist connection of the mysterious and exotic with Asia and the Middle East during a time when Chinese nationals were prevented from immigrating to the United States through the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Omissions and exclusions of Black and Asian magicians are evident in both collections. Colleary also pointed out that many times women were recorded as assistants on stage, rather than magicians in their own right even if they were better than their male counterparts. Hermann the Great may be well-known in magic performance circles, but his wife Adelaide might have been just as good or better. While she was featured in a variety of ephemera, she has only recently started getting the same attention from researchers.

Colleary noted that there’s research potential in searching these older collections for LGBTQIA+ magicians who were not openly or publicly out. The materials may not explicitly reflect or identify their queer identities, but deep diving into the archives can reveal hidden histories of queer performers in magic.

The history of racism and exploitation is evident in many of the white performers’ stories. Some magicians took stage names and personas of other nationalities and ethnicities, often from the China, to further their careers, such as William Ellsworth Robinson (1861–1918), a white magician whose stage name was Chung Ling Soo. Robinson appropriated his name and act from the Chinese magician Zhū Liánkuí, who performed under the stage name Ching Ling Foo. Born in Beijing, he sold out shows in China and the United States, performing for the Empress Dowager Cixi in China and attracting the admiration of Harry Houdini. When Robinson took a stage name very close to Zhū’s, they became rivals; both claimed to be “The Original Chinese Conjurer” while calling the other magician a fraud.

When Zhū showed up in London in 1905, he discovered that Robinson had already established himself there, performing as Chung Ling Soo. Zhū challenged Robinson to a magic duel, offering him £1,000 to recreate 10 of his tricks, but Robinson failed to follow through—and instead demanded proof of Zhū’s own Chinese heritage. This act of blatant racism brought Robinson significant fame until his death in 1918, when his Marvelous Bullet Catching Feat failed.

An attempt to deport Zhū was unsuccessful, but he elected to return to China in 1900, coming back to the United States in 1912 thanks to the advocacy of Oscar Hammerstein. Zhū’s son and adopted daughter, Chee Toy, continued to be part of his U.S. magic act on his return, and Chee Toy would go on to have her own entertainment career, working with Hammerstein. (For more information, check out Samuel Porteous’s 2020 book Ching Ling Foo: America's First Chinese Superstar.)

MAGIC AND ILLUSION AT THE UT AUSTIN HARRY RANSOM CENTER

The UT Magic and Illusion collection is housed within the larger performance archive at the Ransom. Vaudeville impresario and philanthropist Karl Hoblitzelle, who established UT Austin’s Hoblitzelle Theatre Arts Library in 1948, purchased the theater photographs of the Albert Davis Collection—“one of the largest private collections of theater photography in the world,” according to Colleary.

Davis was a fan of both theater and sports, and collected some 100,000 photographs of both disciplines. The sports photography collection is housed in the university’s H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports; the acquisition of the theater photography led to the establishment of the Ransom’s performance archive.

But it was not until 1958 that the Ransom Center began collecting items related to magic and illusion in earnest, with Hoblitzelle’s acquisition of the Harry Houdini papers from New York real estate developer Messmore Kendall.

Kendall acquired the collection almost by accident, noted Colleary. In the 1920s, Kendall lost an auction for a bookcase to Houdini. But when Houdini died, he reached out to the magician’s wife, Bess, to purchase the bookcase. In Houdini’s apartment, Kendall took note of the materials that Houdini had collected, and Bess replied that she was eager to get rid of them. Kendall ultimately purchased it all, minus items that had already been collected by the Library of Congress. Hoblitzelle eventually purchased the Houdini collection for UT Austin—the bookcase now sits outside Colleary’s office.

The Houdini collection includes correspondence with his wife and fellow magicians, contracts and press kits for his film company, photographs, and his dramatic library—including both 19th-century American actor Edwin Booth’s prompt book for Richard III and 18th-century English actor David Garrick’s travel diary— as well as the papers of magician Henry Evans Evanion, who gave them to Houdini. At the time of his death, Houdini’s was “the one of the most impressive magic book collections in the world,” according to Colleary. It’s a remarkable collection, Colleary said, with traces of ownership where people signed objects or included color commentary on performers.

|

Strobridge Lithographing Company, 1894Courtesy of University of Texas Austin Harry Ransom Center |

Other Magic and Illusion collection holdings include the magic books of Morris N. Young and John McManus, added in 1957—although the bulk of the collection predates Houdini’s death in 1926. The Early Books and Manuscripts Library at the Ransom holds Houdini’s copy of the 1584 first edition of Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft, which, Colleary explained, may be the first text attempting to debunk the idea of witches by explaining the illusion of performed magic.

Colleary also pointed to playbills and tickets for Black magician Henry “Box” Brown, whose nickname comes from the story of how Brown, born into slavery, mailed himself to freedom in Philadelphia. After he and his family were forcibly separated, a carpenter named Samuel Smith and Brown built a box that would allow him to ship himself, with some rations, to William Robinson (unrelated to the magician above), an operator in the Underground Railroad, in Philadelphia, PA. Once he arrived safely he was given the “Box” moniker, and began a new life as a prolific abolitionist speaker. He also began incorporating magic performances into his speeches as he toured. Houdini saved various pieces of ephemera from Brown’s career.

Together, the Houdini papers and Albert Davis and McManus-Young collections comprise more than 100 archival boxes, 20 flat file drawers of ephemera and manuscripts, and 2,085 volumes.

Academics, writers, contemporary magicians, and classes from UT and the Austin area have made use of the Magic and Illusion collection, researching topics from magicians at the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition to magic practices in the Black performing arts community. In October, Marina Alexandrova, UT Fellow of Slavic and Eurasian Studies, brought her class “Tsars and Mystics” to explore the collection’s holdings on spiritualism. You can book a classroom experience here.

Early magic shop catalogs from the 19th and 20th centuries, mostly from New York and Chicago, help historians see how tricks have been developed, changed, and circulated around the country. “You can sometimes even get hints at where the tricks come from,” Colleary said, “Oftentimes a catalog will say they have exclusive rights to it and they’ll sometimes even credit the creator.”

Most of the archives are not available online, although items are often loaned out to other institutions for relevant exhibitions. The Ransom Center has digitized seven of the Harry Houdini scrapbooks, which contain press clips, letters, photographs, from 1850 to the 1920s. Those interested in visiting the Magic and Illusion collection at UT Austin are invited to fill out a Patron Visiting Form.

THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF MAGIC'S ARCHIVES AND LIBRARY

The AMM museum, archives, and library grew out of the collection of Michigan-based journalist Robert and wife, Elaine Lund. For decades, Robert Lund had collected material on any and all magicians, not only household names. When William Kalush, now a board member of the American Museum of Magic, met Lund in 1978, Lund’s basement was full of file cabinets containing programs, newspaper clipping, photographs, playbills and more. “Nothing was too basic or too ephemeral for him,” said Kalush, who described the collection as a grassroots snapshot of 20th-century magic.

In 1978, the Lunds decided to create the AMM library and archives, self-funding the whole enterprise, in Marshall, Michigan. When Robert Lund died in 1995, Elaine decided to incorporate the organization as a nonprofit. In 1998, she secured the purchase of a former Marshall Public Library building, renamed the Lund Memorial Library in Marshall, MI, to house the materials. When she died, the collections and building became part of the nonprofit.

The heart of the collection comprises items from the 20th century, though some date back to the 16th century, including a deed signed by Reginald Scot (noted above). Magicians have donated their own archives, including book manuscripts—plus a copy of Roget’s Thesaurus that Houdini inscribed in secret code to William J. Hilliar, a magician who wrote a column on magic for Billboard magazine.

The AMM archives have served as source material for a number of popular works, including Kalush’s book The Secret Life of Houdini: The Making of America's First Superhero, coauthored with Larry Sloman. Magic historian Jim Steinmeyer made extensive use of the archive, as well as Kalush’s knowledge, for books such as The Last Greatest Magician in the World: Howard Thurston Versus Houdini & the Battles of the American Wizards.

Like the Ransom Center, the AMM archive and library holdings are largely unavailable online. In 2011, Google Arts & Culture launched a digitization project of some materials. Kalush noted that the AMM is looking digitize more in the near future. People interested in visiting can make an appointment by phone to use the AMM collection for $25 per hour; members get the first hour free.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!