Indigenous Academic Library Serves as a Model for Centering First Nations Cultures, Communities, Collections

For the past 26 years, the Xwi7xwa (pronounced “whei-wha”) Library at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver—the only Aboriginal branch of a university library system in Canada—has served as a model for how educational and community institutions can center the knowledge and experiences of the communities they serve by better representing them in the collections they share.

|

Xwi7xwa LibraryCourtesty of Xwi7xwa Library, University of British Columbia |

British Columbia is home to approximately 203 First Nations, 34 First Nations languages, and 59 dialects: this first glance reveals a large scope of cultural and linguistic diversity, as well as Indigenous histories, experiences, governance structures, and knowledge systems. The University of British Columbia (UBC) Library is one of the largest academic libraries in Canada, with 14 branches and divisions, two campuses, and a large multipurpose teaching and learning facility. For the past 26 years, the Xwi7xwa (pronounced “whei-wha”) Library at UBC in Vancouver— the only Aboriginal branch of a university library system in Canada—has served as a model for how educational and community institutions can center the knowledge and experiences of the communities they serve by better representing them in the collections they share.

Officially opened in 1993, Xwi7xwa aims to decolonize the way information is sorted, cataloged, and shared by more accurately representing Indigenous knowledge and culture. From the very beginning, the Xwi7xwa Library has taken steps to ensure that Indigenous communities are well represented and heard. At the First Nations House of Learning Opening Ceremonies in 1993, Chief Simon Baker of the Squamish Nation named the library “Xwi7xwa,” meaning echo in the Squamish language. True to its name, the library echoes the voices and philosophies of Indigenous people through its collection, services, spaces, and programming.

The concept for the library began with the Indian Education Resource Centre (IERC), which was both a resource center and lobby group for Native education in British Columbia and across Canada from 1970 to 1977. It housed the small research collection of the British Columbia Native Teachers Association (BCNITA), a group of Indigenous educators working to establish an Indigenous teacher training program in British Columbia. In an effort to connect First Nations teachers and educational material with Indigenous classrooms, the Native Indian Teacher Education Program (NITEP), established in 1974, donated its curriculum materials to the library. These materials, and the community relationships forged, formed the foundation for the library’s collection, which continues to develop as Xwi7xwa strives for greater Indigenous representation and engagement.

COLLECTION CARE

Within Xwi7xwa’s history, the library amplifies values placed on relationships formed within Indigenous contexts in order to create a space for Indigenous knowledge creation and sharing. As a result, Xwi7xwa’s commitment to centering Indigenous voices within all aspects of its operation allows Indigenous authors, publishers, and supporters and patrons of the library to take center stage in academic and information spheres. It primarily does so through its classification system.

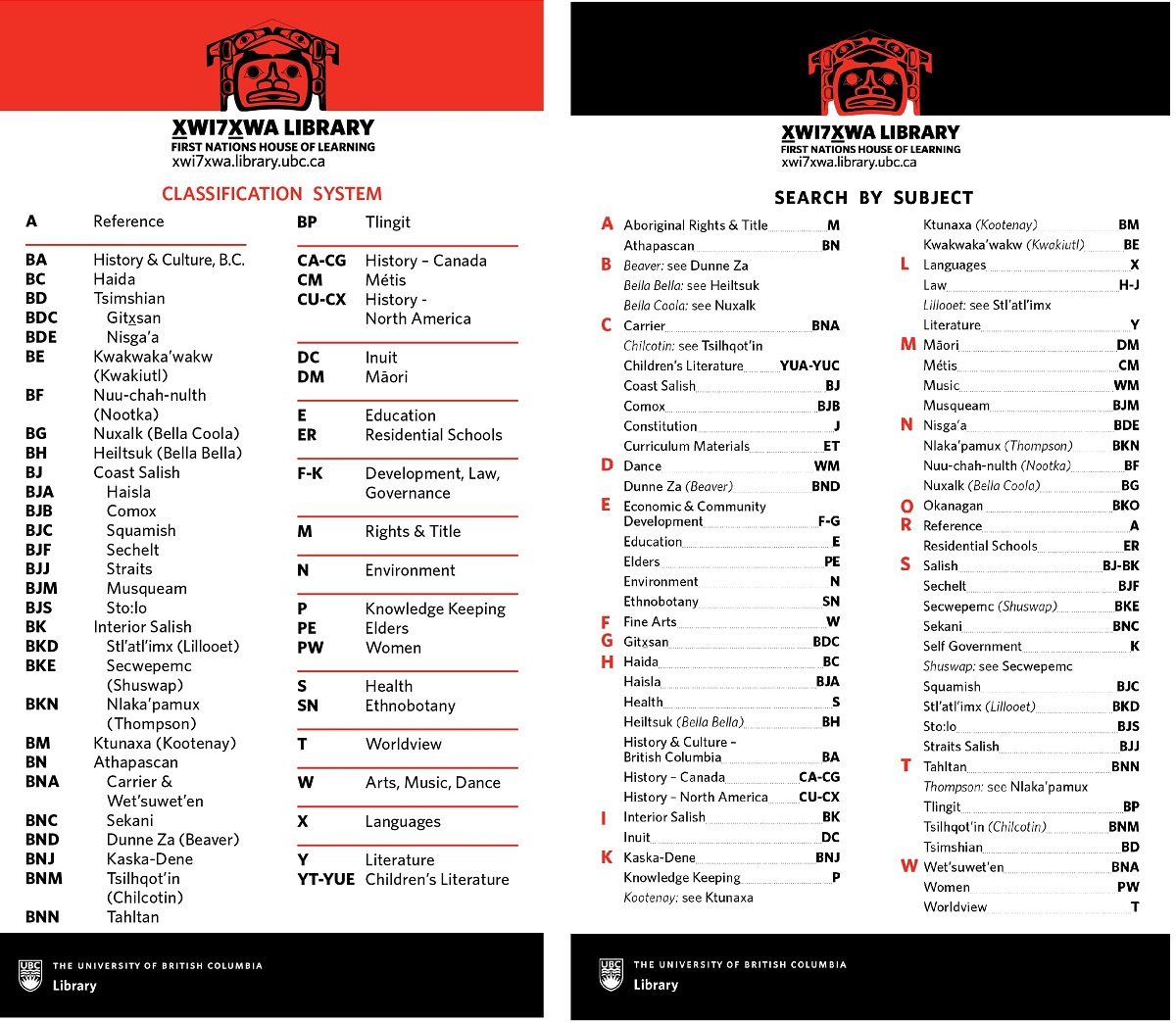

X̱wi7x̱wa uses an adapted version of the Brian Deer Classification System, a cataloging system created in 1974 by Deer, a Kahnawake Mohawk librarian. The system incorporates Indigenous perspectives when categorizing books. One of the most important ways it does this, Adolfo Tarango, acting head librarian at X̱wi7x̱wa, told YES! Magazine, is by using subject headings that reflect a tribe’s preferred name.

Deer designed his classification system while working in the library of the National Indian Brotherhood from 1974 to 1976. Instead of using a standard library classification scheme, he created a new system to organize the library's historic research materials and papers. He went on to work at the Cultural Centre at Kahnawake and the Kahnawake branch of the Mohawk Nation Office, creating new schemas for their collections. The systems Deer created were designed specifically for the materials in each collection according to the concerns of local Indigenous people at the time; for example, categories included land claims, treaty rights, resource management, and Elders' stories. Between 1978 and 1980, the system was adapted for use in British Columbia by Gene Joseph and Keltie McCall while working at the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs. Joseph later became one of the founding librarians of Xwi7xwa.

Though the Brian Deer Classification System was not created as a universal classification solution for Indigenous resources, it has provided a foundation for specialized libraries like Xwi7xwa to create their own localized classification schemes.

|

Indigenous classification at Xwi7xwa Library |

Currently, the Xwi7xwa Library collection is composed almost exclusively of Indigenous materials, consisting of approximately 15,000 items in digital and print formats including monographs, various media, grey literature, serials, dissertations, maps, posters, realia, special collections, and archival materials. The library collects materials created by Aboriginal scholars and work produced by First Nations people and organizations, tribal councils, schools, publishers, researchers, and writers, as well as materials respectful of First Nations perspectives. Users have found that Xwi7xwa’s approach to organizing information provides a safe space and welcoming learning experience for Indigenous and non-Indigenous visitors alike. “They are very much aligned with the way we form relationships with our communities,” Amy Parent told YES! Magazine. Parent, a 2014 UBC graduate and member of the Nisga'a Nation, used X̱wi7x̱wa to conduct research as a graduate student studying Indigenous education.

FIGHTING FOR CHANGE

The success of X̱wi7x̱wa, both in advocating for Indigenous communities and cultivating a stellar collection, didn’t come without challenges. First Nations communities, cultures, languages, and knowledge systems had long been dislocated by successive assimilationist government policies and the Indian residential school system in Canada. These policies continue to impact the quality of Indigenous education experiences everywhere. A 1962–63 national survey of First Nations public education reported that only four percent of registered Indigenous students completed Grade 12, compared to 88 percent for non-Indigenous students. In response, in 1972 the National Indian Brotherhood (now the Assembly of First Nations) prepared a national policy statement, Indian Control of Indian Education, asserting Indigenous jurisdiction over the education of First Nations children. It was ratified by the Canadian government a year later and remains a blueprint for local control in contemporary Indigenous education policy frameworks. As a result of this change, BCNITA established NITEP, leading the way for the Xwi7xwa library.

However, even with such government and organizational backing, Xwi7xwa still relied on community support to keep its doors open. It took "tenacity, dedication, and pure stubbornness" through hard times, according to Joseph. "There were many years when we had very little—or didn't have any—funding, and it looked like the collection was going to die or turn into dust," Joseph stated in the BC Aboriginal newspaper Raven’s Eye. "But there was always some group of people—First Nations people, faculty and staff—who pulled it out of the ashes and brought it back to life again. We were just determined not to let it die."

The determination to not let Xwi7xwa fail and to keep Indigenous community representation at the forefront of its operations is part of a larger battle to change how normalized classification systems, such as the Dewey Decimal (DDC) and the Library of Congress (LCC) classifications, ultimately erase such groups. Mainstream library systems reflect Western methods of sorting information, rather than Indigenous methods. In addition to differing categorization methods, systems like DDC and LCC sort according to alphabetical order, which can’t easily incorporate Native American languages that use non-Roman characters. More important, Western bias plays a large role in the way Indigenous experiences and epistemologies get erased in educational institutions.

For example, the LC E99 class places Aboriginal people in the History of the Americas class and then geographically scatters Indigenous works by arranging them alphabetically. Tsimshian materials from the Pacific Northwest coast of Canada are cataloged beside materials relating to the Tübatulabal people of the interior mountains of California, next to those of the Tukkuth Kutchin people of northern Canada’s Yukon, beside the Tzotzil people of the Chiapas highlands in southern Mexico. This dynamic of dispersal through classification is reminiscent of the dispersal of First Nations children, communities, and lands through colonial government policies. Furthermore, books on Indigenous communities often get looped into the history section. As a result, information on Native peoples literally gets left in the past. To offer an alternative to widely used Western classification systems, Xwi7xwa aims to take steps toward decolonizing the way information is sorted, cataloged, and shared by countering Western, colonial bias and better reflecting the knowledge of Indigenous peoples.

LARGER COMMUNITY NETWORKS

Xwi7xwa isn’t the only library in North America that strives to center Indigenous community experience and knowledge; other organizations and institutions are beginning to take seriously the need for more community input and control over how they are represented.

Northwestern University (NU) Libraries, in Evanston, IL, has embarked on a digitization project to preserve and share regional Indigenous epistemologies. The Native American Educational Services (NAES) Digital Library Project, a collaboration between the American Indian Association of Illinois, NU Libraries, and Northwestern’s Center for Native American and Indigenous Research, is a community-engaged initiative that explores the library and archives of Chicago’s NAES College, the first urban American Indian four-year college run by and serving a Native population. Before it closed in 2005, NAES College—the only independent, Native owned and controlled college in the United States—expanded to satellite campuses on reservations in Montana, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, graduating over 280 students who received a community-based education centered around public policy, tribal knowledge, and community development and leadership. The NAES Digital Library project also shares the stories of those who used and shaped the collection, and centers the experiences and creations that continue to emanate from the institution.

Like Xwi7xwa, NAES College used a Native-centered library classification system developed in the early 2000s, and one of the first project tasks is to incorporate this system into the digital catalog. The second phase of the project will produce a website featuring oral histories from Native teachers, librarians, students, and allies. The third phase will share NU Libraries’ process and practices publicly and will create new learning materials around issues of at-risk collections, community archives, and data sovereignty.

SERVING AS A MODEL

The success of Xwi7xwa Library and the NU Libraries’ NAES project highlights the importance of incorporating community input into institutional efforts to create solutions around inclusive representation and access to knowledge. Both initiatives work within different historical contexts to address representation and knowledge dissemination issues among Indigenous communities that have historically been excluded from educational spaces. On the NAES project website, NU acknowledges these aims through its land acknowledgement in an effort to further highlight its commitment to serving Indigenous communities that have been historically excluded from both educational and knowledge systems.

Northwestern is a community of learners situated within a network of historical and contemporary relationships with Native American tribes, communities, parents, students, and alumni. It is also in close proximity to an urban Native American community in Chicago and near several tribes in the Midwest. The Northwestern campus sits on the traditional homelands of the people of the Council of Three Fires, the Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa. It was also a site of trade, travel, gathering and healing for more than a dozen other Native tribes and is still home to over 100,000 tribal members in the state of Illinois.

It is within Northwestern’s responsibility as an academic institution to disseminate knowledge about Native peoples and the institution’s history with them. Consistent with the university’s commitment to diversity and inclusion, Northwestern works towards building relationships with Native American communities through academic pursuits, partnerships, historical recognitions, community service and enrollment efforts.

In a similar vein, the Xwi7xwa Library is successful in large part because of the commitment of First Nations leadership to Indigenous education, the ongoing support of the wider Aboriginal community, the intellectual legacy of First Nations librarians, and the individual and collective efforts of those who advocated for an Indigenous academic library. Because of such efforts, the Xwi7xwa Library has been integral to the development of Indigenous education in British Columbia and plays a role in the continuing Indigenization of education, decolonization, and reconciliation efforts. (See also First Archivist’s Circle’s Protocols for Native American Archival Materials.) As the original founders of the library wrote, “Xwi7xwa is a product of Indigenous vision, persistence, innovation, and perhaps social justice.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!