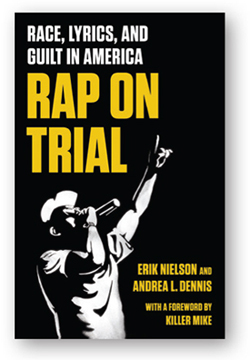

LJ Talks to Erik Nielson & Andrea L. Dennis, Authors of Rap on Trial

In their new book, Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics and Guilt in America, Erik Nielson and Andrea L. Dennis show how aspiring rappers have often fallen victim to a corrupt justice system, as prosecutors twist lyrics into evidence of murder, assault, drug trafficking, and other crimes.

Since hip-hop’s inception, rappers have fearlessly spoken truth to power. And for just as long, those in power have weaponized the genre, using artists’ words against them, from FBI attempts to intimidate the group N.W.A into no longer performing the song "Fuck tha Police" to a police campaign against Body Count’s self-titled album, which featured the incendiary "Cop Killer."

Since hip-hop’s inception, rappers have fearlessly spoken truth to power. And for just as long, those in power have weaponized the genre, using artists’ words against them, from FBI attempts to intimidate the group N.W.A into no longer performing the song "Fuck tha Police" to a police campaign against Body Count’s self-titled album, which featured the incendiary "Cop Killer."

But the phenomenon isn’t limited to established artists, argue Erik Nielson and Andrea L. Dennis. Their book, Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics and Guilt in America (New Pr., Oct., LJ 10/19), explains that aspiring or amateur rappers have also fallen victim to a corrupt justice system as prosecutors twist lyrics into evidence of murder, assault, drug trafficking, and other crimes.

Over the past decade, Nielson and Dennis have discovered around 500 such cases, but there are likely many more cases that never made it to trial or that are sealed because they are juvenile records. And the general public remains unaware, largely because this is an issue facing black and Latinx men. "People tend to be dismissive" about "young men from the inner city going to jail," Dennis, a professor at the University of Georgia School of Law and a former public defender, told LJ.

Calling for accountability

A close analysis of cases is disturbing. First Amendment protections often don’t apply when it comes to rap. Take the case of Jamal Knox and Rashee Beasley, who recorded "Fuck the Police," a homage to N.W.A.’s hit song that named officers who had arrested the two in the past. Months later, Knox and Beasley’s friend Leon Ford Jr. was shot by police who mistook him for another man; Ford survived but was paralyzed. Soon after, "Fuck the Police" was uploaded to YouTube and discovered by police officers monitoring Knox’s and Beasley’s social media accounts, and Knox was convicted of making terroristic threats. On appeal, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld the trial court’s ruling that the song wasn’t protected by the First Amendment because the lyrics did not "include political, social, or academic commentary, nor are they facially satirical or ironic."

The court’s refusal to acknowledge the song’s artistic intent speaks volumes, says Nielson, who teaches classes on hip-hop and African American literature at the University of Richmond. He adds, "I can’t imagine something that is more rooted in social and political commentary than a song called ‘Fuck the Police’ by a kid who’s mad at cops who have been terrorizing his neighborhood and paralyzed his friend."

The court’s refusal to acknowledge the song’s artistic intent speaks volumes, says Nielson, who teaches classes on hip-hop and African American literature at the University of Richmond. He adds, "I can’t imagine something that is more rooted in social and political commentary than a song called ‘Fuck the Police’ by a kid who’s mad at cops who have been terrorizing his neighborhood and paralyzed his friend."

The authors cover a range of other alarming cases. Young men who appear in rap videos that also feature gang members are accused of having gang affiliations, and so-called expert witnesses often misinterpret slang. In a 2014 trial against Deandre Mitchell, accused of a drive-by shooting, a detective analyzing Mitchell’s song lyrics erroneously claimed that "to ride" meant "to shoot."

Though it may seem like cops or prosecutors unfamiliar with hip-hop are merely making mistakes about the language, Nielson refuses to let them off the hook. "This isn’t happening to white people. This isn’t happening to other forms of music where white people are the primary creators," he says. "There are open, blatant attempts to misrepresent the music and people who create it. It’s willful, and people are doing it with their eyes wide open."

Igniting impact

As bleak as the situation is, Nielson and Dennis’s articles publicizing these cases, as well as Nielson’s work testifying as an expert witness in trials where rap lyrics are used as evidence, have started to have an impact.

"Because of our efforts, more and more people are aware of it," says Nielson. "Years ago, when I started doing this, I would get a call from a desperate defense attorney who was already in trial" or about to go to trial.

But now they can intervene earlier, as they did for Drakeo the Ruler, a well-known Los Angeles rapper charged with murder and possession of a weapon. A journalist covering the case contacted Nielson and Dennis, who were able to help find the artist a better legal team; Drakeo was acquitted of most of the charges in 2019.

Dennis, who has seen firsthand how the legal system is stacked against defendants, says that staying hopeful is hard but not impossible. "Some of it is learning to accept that a complete and absolutely not guilty verdict is unlikely, a complete dismissal of charges is unlikely, but there are small successes, in convictions on fewer charges, convictions on charges that have lesser sentences, saving someone’s life if they are facing the death penalty."

Above all, the authors want readers to know they can make a difference. Both advocate for jury nullification, or jurors’ option to return a not guilty verdict to protest unjust laws or practices.

"Look at what communities have done around marijuana," says Nielson. "In many communities, prosecutors understood that they weren’t going to be able to bring the charges anymore, because juries just weren’t going to go along with it anymore."

And because the jury system requires a unanimous verdict, Nielson says, "It’s one of the rare sorts of moments...where a lone person can throw a wrench into a very big apparatus. But that is precisely what a juror can do."—Mahnaz Dar

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!