Gotta Sing the Blues: The Blues Archive at the University of Mississippi

Since its founding in 1984, the University of Mississippi’s Blues Archive has collected virtually everything related to the Blues, from sheet music, concert tickets, and recordings to record label business files and even clothing. Thanks to a website revamp and a multiyear grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) to digitize materials, this year the archive is starting its 40th anniversary in style.

|

Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” was hugely successful and helped usher in the era of “race records,” the industry term at the time for Black music. While there are earlier blues recordings, this one sold so well that record company executives realized there was a market for this type of music.Photo by Greg Johnson |

Since its founding in 1984, the University of Mississippi’s Blues Archive has collected virtually everything related to the Blues, from sheet music, concert tickets, and recordings to record label business files and even clothing. Thanks to a website revamp and a multiyear grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) to digitize materials, this year the archive is starting its 40th anniversary in style.

The Blues Archive was officially founded in 1984, but the seeds of the collection already existed. While the library likely had been collecting items from around the state since its opening around 1849, a donation in 1924 of Mississippi items jumpstarted librarians to collect various material, everything from works by authors to music recordings, which included Mississippi blues musicians.

That was only the start, however. Dr. William “Bill” Ferris, founding director of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the university in the late 1970s, convinced his former professor, the late Dr. Kenneth S. Goldstein, to donate the majority of his collection of American folk music to the library; Goldstein’s collection included an abundance of Anglo Celtic music but also early blues. (The non-blues music collection is also housed at University of Mississippi and Middle Tennessee State’s Center for Popular Music.) In addition to teaching folklore and serving as chairman of folklore and folklife department at the University of Pennsylvania, Goldstein also served as producer and music editor at several early blues labels, including Prestige, Stinson, and others.

Ferris had many connections in the blues world himself, having written about the genre in numerous publications. Plus he was a friend of legendary blues musician B.B. King; Ferris convinced King to donate his personal record collection to the archive around 1982.

Ferris also worked out a deal with the Chicago-based Living Blues Magazine—the first U.S. blues magazine, founded in 1970—to acquire the publication in 1983, and Living Blues moved its operations to the university. Its archives include blues posters, photos, flyers, press releases, as well as the business files. The magazine publishes bimonthly through the Center for the Study of Southern Culture.

With these major acquisitions, along with the early Mississippi recordings, Ferris and others at the university established the Blues Archive in 1984. B.B. King’s record collection and the Living Blues Magazine archives started “a domino effect,” explained Greg Johnson, head of special collections, blues curator, and professor at the University of Mississippi Archives and Special Collections. People began donating additional materials and have continued to do so.

Johnson estimates that the archive has close to 100,000 sound recordings, about 200,000 photographs, and more than 34,000 books, periodicals, and newsletters, along with extensive holdings of concert tickets, concert programs, and clothing (like blues festival t-shirts and hats).

THE BIRTHPLACE OF AMERICA’S MUSIC

The University of Mississippi is a logical place for the Blues Archive, Johnson feels. “Whenever anybody’s driving into Mississippi on any of the interstates coming into the state, they’re greeted with the welcome signs, which state, ‘Welcome to Mississippi; Birthplace of America’s music,’” he said. The blues came out of the Delta region of the Mississippi and North Mississippi Hill Country, he noted, and Mississippi is the birthplace of both Elvis Presley (Tupelo) and Jimmie Rodgers, the “father of country music,” in Meridian.

While Johnson acknowledged that many states contributed to American music, “blues is at the heart of so much” of America’s music, he said. The music of country singers Hank Williams and Rodgers was rooted in the blues; blues singer and musician Muddy Waters aptly sang, “The Blues Had a Baby and They Named It Rock and Roll.”

The archive’s materials are available for the public to listen to, read, and peruse. Someone who wanted to hear rarer recordings, such as an original Robert Johnson 78, would ordinarily have to find a private collector to listen. (Yale University Library describes a 78 as a record made between 1898 and the 1950s, with a speed of 78 revolutions per minute. Johnson was a blues musician whom the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame called the “first ever rock star.”) But people can also find these recordings at the University of Mississippi Blues Archive, Johnson explained.

The archive’s largest focus is the period during the 1920s and 1930s, when blues became a commercially recorded genre after the extraordinary popularity of blues musician Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” in 1920. The archive stretches back to the 1830s through the present, including artists who released albums last month. Johnson explained that it’s important for the archive to collect local artists, as they often release small-run recordings regionally, and these may not be available after a few years.

In addition to rare recordings, the archive contains the business records of Mississippi-based label Trumpet Records, founded by Lillian McMurry in 1950. Trumpet recorded many genres of music, including rockabilly, jazz, country, gospel, and the blues. McMurry’s studio was the first to record some of the blues greats, like Sonny Boy Williamson and Elmore James. The label’s business records include all of its recording contracts, correspondence with artists, and royalty statements.

Johnson noted that while King’s record collection contains the expected blues and jazz, it also holds country and comedy albums. King even had 50 foreign language course LPs, including a record of Serbo-Croatian instruction. In 2004, when the university made King an honorary professor of Southern Studies, Johnson asked him about the language records. King explained that when he went on his first world tour, he wanted to learn a few phrases of every language spoken in the places he was playing.

Some of the oldest items in the collection are minstrel show sheet music from the 1830s. Minstrelsy was a racist theater tradition that became popular in the 19th century with white audiences across the country—particularly in the Midwest and North—where white musicians dressed in blackface and mocked African Americans and their music. This practice bolstered and popularized racist stereotypes of African Americans and other people of color, and is part of a long tradition of white artists stealing Black music for their own financial gain.

While the practice of minstrelsy was harmful and violent, Johnson explained that minstrel songs influenced the development of the blues and many other American music styles: “A number of early blues singers began their careers performing in minstrel shows. While many minstrel shows featured white performers in blackface, many of them featured African American performers as well,” he said. “Sometimes even the African American performers were in blackface. It is a very complicated subject.”

As a popular form of music, he added, it could be lucrative for performers. “The famous Rabbit’s Foot Minstrels included in its ranks a number of performers who would go on to be pivotal figures in the world of blues—often blues songs were sung at minstrel shows in the first half of the 20th century,” he said. Those performers included Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Ida Cox.

Some of the sheet music from this era contains racist descriptions and depictions, Johnson added, noting, “It’s important for people to be able to see exactly why the civil rights movement came to be. People need to see examples of what I'll call ‘civil wrongs.’” In view of the offensive language and imagery, the archive provides content disclaimers online for the digitized music.

EVERYBODY SINGS THE BLUES

|

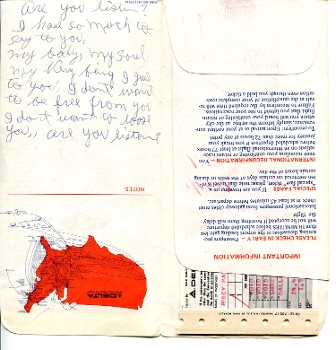

Delta airlines envelope with lyrics scribbled by Percy MayfieldPhoto by Greg Johnson |

Since its inception, the archive has tried to collect blues material on a comprehensive scale, from local talent to blues musicians worldwide. Johnson noted that he would like to increase the collection’s work “documenting local blues scenes, or regional blues scenes throughout the world”—representing more musicians outside of Mississippi.

The archive is used by students, educators, scholars, and hobbyists. Johnson regularly speaks to students across the University of Mississippi campus, from music history classes to the Freshman Year Experience class that helps first year students bridge the gap from high school to higher ed; learning about the Blues Archive showcases the history of the university and the state. Johnson has also worked with accounting and legal classes to review the business records of Trumpet Records, giving students a look at how an independent music label managed money in the 1950s. For a contracts class in the law school, students studied Trumpet Records’ contracts with its artists.

Local elementary school students and high schoolers often visit the archives. Blues societies and the Road Scholars, a nonprofit education travel program for older adults, have also taken field trips to view them.

The collection has been used by scholars, writers, and filmmakers, such as journalist Daniel de Visé, for his biography King of the Blues: The Rise and Reign of B.B. King; George Washington University professor Gayle Wald, author of Shout, Sister, Shout!: The Untold Story of Rock-and-Roll Trailblazer Sister Rosetta Tharpe; and University of North Georgia professor and historian Ben Wynne, for his book In Tune: Charley Patton, Jimmie Rodgers, and the Roots of American Music. Martin Scorsese used the collection for the seven-part PBS film series The Blues, which he produced in 2003, which included photos from the collection.

Currently Johnson is working on making the archives even more accessible. Thanks to the NHPRC grant received in fall 2023, he is able to digitize more of the collection. Some, such as the sheet music, were digitized in 2005, but the grant will fund the digitization of audiovisual materials, which he speculates comprises almost a petabyte of data. Over approximately the next three years, Johnson aims to have the archive’s videos, 16 mm film reels, Super 8 film reels, and cassettes made available on the website, although some content may be limited internal university use because of copyright restrictions. He also hopes to create transcripts of spoken word content. In honor of the archive’s 40th anniversary, Johnson is planning a mini-exhibition in the library for the fall.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!