Diane Scharper

92 Articles

Last 30 days

Last 6 months

Last 12 months

Last 24 months

Specific Dates

From:

To:

PREMIUM

Dream Apartment

At their best, these poems work their magic through just such a sequential movement.

Paper Banners

Miller is able to go inside her subjects and draw readers with her. That experience makes this collection one for all libraries.

Miller is able to go inside her subjects and draw readers with her. That experience makes this collection one for all libraries.

PREMIUM

The Wild Hunt Divinations: A Grimoire

There’s an artfulness of intention behind this work, but placing these anagrammed lines beside those of Shakespeare doesn’t enhance it. Ketner may have discovered an ingenious technique, but unfortunately their method does not result in ingenious poetry.

PREMIUM

Mare’s Nest

Ultimately, Mitchell’s language is reminiscent of Dylan Thomas’s “Fern Hill” and draws from a similar source: life bursting forth on the farm beside an undercurrent of death. As Thomas’s famed line says, “Time held me green and dying/ Though I sang in my chains like the sea.”

PREMIUM

Still Falling: Poems

Coming from deep inside, these poems work by free association, often alluding to falling rain, snow, and even sunlight pouring onto a surface, all of which add a spiritual resonance to these hypnotic and meditative poems.

PREMIUM

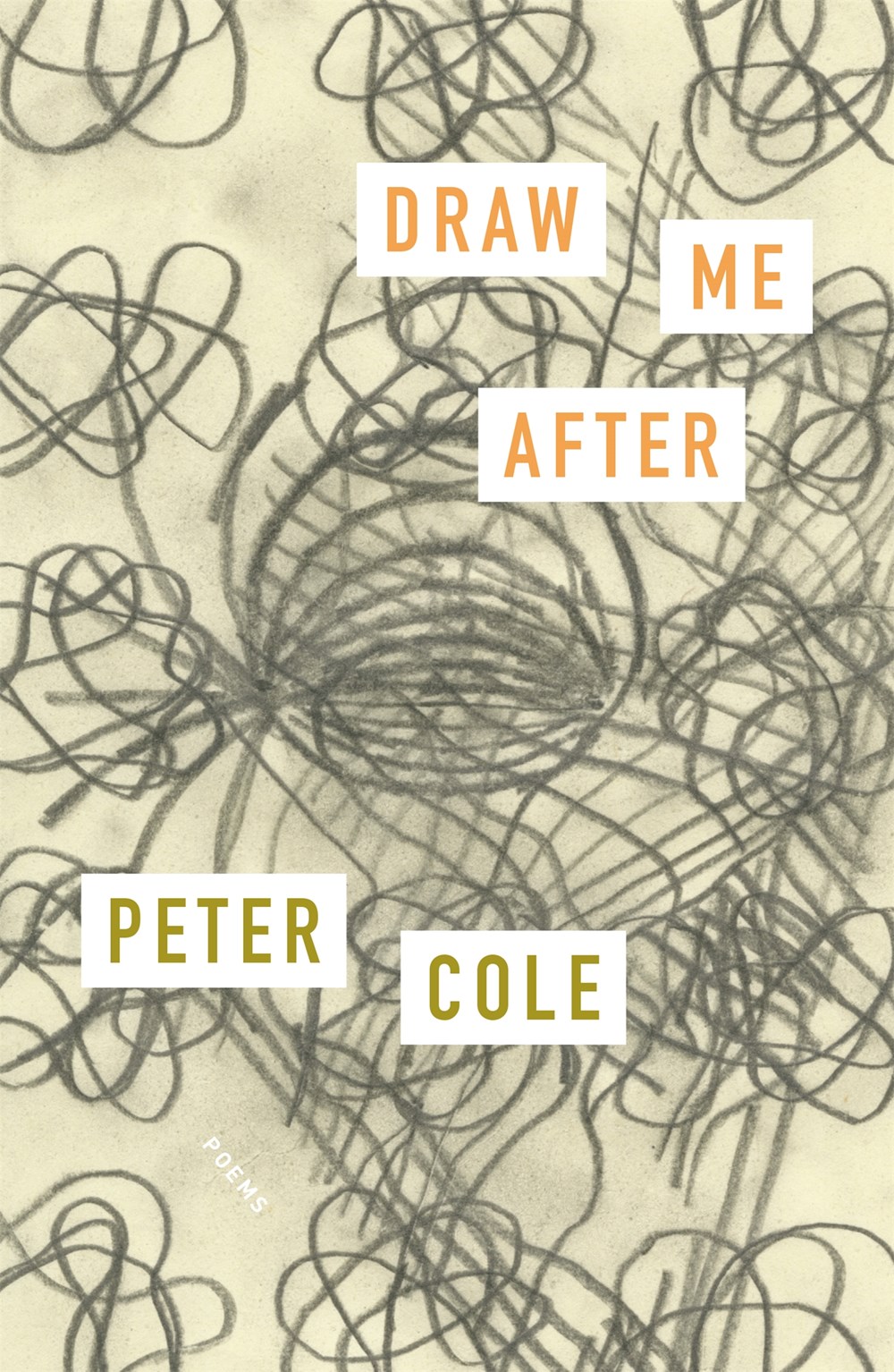

Draw Me After: Poems

Coming from Cole’s fascination with word play and paradox, the best of these poems are laced with alliteration and rhyme, shape-shifting as they focus on the letters of the Hebrew alphabet and the creative process. For poetry readers who like pondering deep questions.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing