Libraries Defying the Odds: Breathitt County Receives LJ/Gale Award, Charleston County Takes Honorable Mention

When a series of unanticipated hardships hit Breathitt County, KY, its library came forward to serve residents in large and small ways. For its critical community work now and looking ahead, Breathitt County Public Library is the recipient of LJ and Gale's inaugural Libraries Defying the Odds award. Charleston County Public Library, SC, is awarded honorable mention for its ongoing work to address food insecurity.

Breathitt County Public Library is the inaugural Gale/ LJ Libraries Defying the Odds award recipient

Breathitt County Public Library (BCPL), in Jackson, KY, is an essential component of its community. The library, serving a rural population of just over 13,500, in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains in southeastern Kentucky, is the only source for local movie rental and book checkouts, as the county does not have a bookstore, movie theater, or video-rental outlet. Residents also depend on it for broadband, fax, scan, and copy services; laptop lending; Wi-Fi hotspot checkouts; meeting rooms; and a safe, climate-controlled space for rest and entertainment.

|

RIVER TOWN Jackson, KY, surrounded by the North Fork of the Kentucky River. Photo ©2023 Bob Hower/Quadrant Inc. |

When a series of unanticipated hardships hit Breathitt County—COVID-19 shutdowns in 2020 and historic flooding disasters in 2021 and 2022—the library came forward to serve residents in unanticipated ways. From a rapid move to remote services during the pandemic to connecting residents with emergency services, providing shelter and connectivity, and helping a town process its trauma, BCPL’s staff of five continued stepping up to meet the tight-knit community’s needs.

BCPL’s ongoing commitment to responsive and compassionate service in both good times and bad—over the past several years and looking ahead—has earned it LJ’s inaugural Libraries Defying the Odds award, sponsored by Gale, part of Cengage Group.

|

AFTER THE DELUGE A house submerged by the 2022 flood; demolishing a destroyed home after floodwaters receded. Photo courtesy of Breathitt County Public Library |

PANDEMIC INNOVATIONS AND ISSUES

With the advent of the pandemic in early 2020, BCPL shifted gears to adapt to closures and, after reopening that June, social distancing. Extended Services and Cataloging Librarian Susan Pugh (who notes that, along with the library’s other four employees, she often serves a wide variety of roles), began creating virtual story hours and take-home craft bags to accompany them.

Pugh collaborated with Breathitt County Extension Service agent Kayla Watts to offer mental health resources for teens and adults, and developed adult coloring kits and crafts. “I created a genealogy kit, and we gave them all the tools they needed to start working on their family tree, because that was something you could do at home,” says Pugh. A socially distanced program, Explore Breathitt, encouraged community members to go out and visit a variety of spots in the county, then post a photo on their social media account and tag the library. The program was so popular that it eventually expanded into surrounding areas of eastern Kentucky.

|

FIVE STARS BCPL staff (l.-r.): Thelma Gross, Library Aid; Misty Little, Library Aid; Sandra Napier, Library Aid; Susan Pugh, Librarian. Inset: Executive Director Stephen D. Bowling. Photo ©2023 Bob Hower/Quadrant Inc., inset photo courtesy of Breathitt County Public Library |

BCPL has incorporated many of the programming and service innovations developed during the height of the pandemic into its current options, says Pugh. But local connectivity issues continue to pose roadblocks for many in a community where a third of the residents—including nearly 43 percent of those under age 18—live below the poverty line. According to U.S. Census Bureau numbers from 2017 to 2022, 71.6 percent of households in Breathitt County have broadband services, and local schools distribute Chromebooks to students. But this does not address the need for technology for all family members, and many remote workers are challenged by low internet speeds or inconsistent broadband stability.

TWO 100-YEAR DISASTERS

In March 2021, as libraries across the country were beginning to reopen, catastrophe hit Jackson when the North Fork of the Kentucky River flooded. “We opened up the library and became a shelter,” says Pugh. “We gave out water, we gave out food, we gave out cleaning supplies. And we thought we were good—it was a 100-year flood. We’d never see this again in our lifetime.”

A 100-year flood isn’t one that happens once in a century, however. Rather, the term describes an event that has, on average, a one in 100 chance of being equaled or exceeded in any given year. And in late July 2022, a second 100-year flood hit Jackson, the worst since Breathitt County began keeping records in 1828. Stephen D. Bowling, BCPL’s executive director since 2001, has been a volunteer member of the Jackson Fire Department since 1986, and has seen his share of adversity. “This surpassed anything that we could even have imagined,” he says. “It destroyed 600 or so homes in our community.”

|

HELP WHERE IT'S NEEDED Top photo: Red Cross setup in the library. Bottom photo: water distribution to residents after the flood. Photos courtesy of Breathitt County Public Library |

BCPL’s hilltop site helped it avoid the worst of the flooding. After closing for a day to allow staff to help family and neighbors—while no employees lost their homes, everyone knew somebody affected by the disaster—the library opened its doors the following morning. Floodwaters had closed Highway 15, the main throughfare, so “Associated Press reporters, photographers, FEMA [Federal Emergency Management Agency] folks were here sleeping on our floor,” Bowling recalls. In addition to providing lodging for the press and FEMA, staff spread the word that people could come in to sleep and use the electricity, internet, and air conditioning.

Outreach was the next priority. The flood had destroyed phone lines and providers’ offices and equipment; many parts of the county had no communication services for weeks. Water lines and wells were destroyed, and the local water treatment plant flooded, leaving the county without water for weeks.

“Obviously, people were not coming to the library,” says Bowling. “We sent our staff out with water and cleaning supplies. We started visiting people we knew who were regular users of the library, and did checkups. Sometimes we mopped mud out of houses. We had requests to pick up medicine.”

|

|

ALL HANDS ON DECK Community partners and BCPL staff Top photo (l.-r.): Jackson Police Department Chief Brian Haddix, BCPL’s Misty Little and Sandra Napier, University of Kentucky Family and Consumer Sciences Extension Agent Stacy Hounshell, and University of Kentucky Cooperative Extension Service contact Lane Hall. Bottom photo (l.-r.): Hack Hudson, Literacy Coordinator for Breathitt County Schools; University of Kentucky Agriculture and Natural Resources (ANR) Extension Agent Reed Graham;Jackson Police Department Captain Elvis Noble, and BCPL’s Sandra Napier. During the pandemic, Breathitt County Schools cosponsored literacy events at the library and provided overflow space for FEMA, library materials, and community resources. After the flood, ANR agents helped restock and replenish county gardens through a library seed program. Photos ©2023 Bob Hower/Quadrant Inc. |

A HUB FOR RESOURCES

Thanks to strong community partnerships and longstanding relationships with the local government, Breathitt County Cooperative Extension Office, Breathitt County Schools, Jackson Independent School District, Breathitt County Health Department, and various other agencies, plus state and federal aid, the library was able to rally help where it was needed. But perhaps the most vital components were BCPL’s five staff members.

Other than Bowling’s work with the fire department, staff had no prior training in disaster response. But figuring out ways to help the community wasn’t just a service mandate—it was personal. Jackson has a population of about 2,200 people, while Breathitt County is home to under 13,000. “We all knew people,” says Pugh.

Misty Little, who manages the library’s archives and children’s programming, among other initiatives, notes that flooding isn’t uncommon in that part of Eastern Kentucky, but the complete devastation after the 2022 flood came as an enormous shock. People didn’t know what to do, what agencies could help them, or how to even approach getting help when they’d lost everything, including home deeds, car titles, and birth and marriage certificates.

“I’m on the radio, so we could get the word out that all the emergency agencies had contacted us as if we were the central hub,” says Little. “We immediately started pushing that information out on Facebook. We had the Red Cross here, we had FEMA, we had all kinds of long-term-recovery people in the building. We were pushing the message to the community: ‘Come to us if you were flooded, if you had damages, if you lost things. All your community resources are here in one spot.’”

|

TEMPORARY DIGS Library space taken over by FEMA to assist residents in the aftermath of the flood. Photo courtesy of Breathitt County Public Library |

FEMA IN THE LIBRARY

Hosting FEMA was a critical component of the resources BCPL provided. Originally, Watts wanted to offer the agency the county extension service offices, but FEMA needed more space than the county could provide, both for FEMA employees and residents who would need to speak with them in person. “In a small community, there’s not a lot of facilities that have ADA accommodations, accessible internet, lots of technology,” she says. When the county asked, BCPL agreed to accommodate FEMA operations.

FEMA’s presence in the BCPL Annex Building adjacent to its main facility became a vital part of disaster relief and recovery in the first weeks. “If FEMA couldn’t have set up at the library, they probably would have been placed in another county, which a lot of our people couldn’t travel to to receive those services,” Watts says—or FEMA would only have been in Jackson a few days out of the month, creating confusion and obstacles for locals who were already experiencing enormous challenges. “I really don’t feel like all the people would have received the help they needed otherwise.”

Bowling agrees, noting that on one day alone, 11,000 people came through the library, with lines outside stretching down the block. “They would have had to drive 44 miles, if they had a car left, if FEMA hadn’t been here,” he says. One man who walked six miles each way from the nearby town of Haddix just to reach the library. “We canceled all our programming, we canceled everything we scheduled for those rooms, because there was just no other way.” Other agencies used library facilities and resources as well, including the local Small Business Administration, Kentucky Emergency Management, American Red Cross, Social Security Administration, Division of Child Services, Breathitt County Health Department, local mental health professionals, and others.

Simply giving space to FEMA wasn’t enough, however. The language of government bureaucracy wasn’t easily understood by many community members just beginning to deal with the extent of their losses; some elderly residents who didn’t have cell phones or computers were being asked to provide email addresses for government communication. “We have a library email that we opened up so that they could send and receive documents, and we could print them,” Pugh says. “We turned into a go-between with FEMA. Because [residents] knew us, they could relate to us. We could print things and say, ‘Here it is,’ so they could read it for themselves.”

Even those experienced with technology struggled when their homes were destroyed and their devices lost. “FEMA would say, ‘We need this, this, and this,’” Pugh says. “And people would say, ‘It’s washed down the river. We don’t have it.’” When library workers saw that people couldn’t get the help they needed from FEMA without paperwork verifying identification and property ownership—which had often been destroyed or disappeared in the flood—they realized they had to step in and help. With no formal training, staff began researching online and making calls about what residents needed to get copies of everything from house deeds to Social Security cards and birth certificates. “It’s not something we learned in library school,” Pugh says wryly.

|

ON BOARD Breathitt County Public Library Board of Trustees (l.-r.): Secretary Terri Young; Board Member Harold Holbrook; Vice-President Karen Griffith. Photo ©2023 Bob Hower/Quadrant Inc. |

This wasn’t just a matter of getting people onto the right website, Little adds. “We would say, ‘Here’s Kentucky Vital Statistics, let’s get you a new birth certificate, or let’s walk you over to the courthouse, this is where you get a copy of your deed. We were really boots-on-the-ground, trying to help people recover things.” The library also provided childcare and activities for children while their caregivers applied for aid, complimentary copies and faxes of any required documents, notary services, free public computers, a disaster recovery wall of essential documents and forms, and donated resources including water, food, clothes, blankets, hygiene items, and more.

“There were times [I was] there when the door opened, and they would try to help me track somebody down,” says Rena Hamblin, a retired teacher who lost her home in the flood. If staff didn’t know the answer to a question, she adds, they would do the work necessary to find out. “That totally was not their job, but they did it. They did it selflessly. They went above and beyond.”

LONG-TERM CONCERNS

Bowling, Little, and Pugh realized early on that people needed emotional support as well. “People just wanted to be heard,” Little says. “They wanted to share their story with someone. There were so many times when you got to hear a story of rescue or survival, ‘How I’ve made it through.’”

Pugh adds, “They just wanted to tell you what happened to them and try to work through it in their own way. Sometimes you became a counselor, sometimes you became a librarian, sometimes you became a tech person—whatever that person needs.”

In many cases, it deepened relationships staff already had with residents. “Some of our older folks who don’t have a lot of family, we were their family during this,” says Bowling.

Many are dealing with the fallout a year later, Bowling notes. “We still have people living in tents who refuse to leave their property. We still have FEMA trailers. We still have lots of people who haven’t moved furniture or anything out of their homes that’s salvageable because they’re paralyzed by what happened,” he says.

The county’s children have been hit hard as well. When Pugh recently visited a local preschool for monthly story time, the teacher told her that a few days earlier, it had rained—nothing threatening—but several of the children began piling up blocks to climb and escape from the water. “The school provided mental health resources to the teachers and students,” she says, “but how can you explain to a three-year-old that just because it’s raining doesn’t mean the floods are coming back?”

“There are undiagnosed issues that aren’t being treated or talked out,” says Bowling. “We’ll see that for the next 25 years.”

To help people verbalize what they’ve been through, the library has invited them to help document the flood for the Breathitt County Heritage Center, BCPL’s local history and genealogy collection. “We do a lot of work in recording and preserving local history,” says Bowling. “Rather than saying, ‘How’s your mental health,’ we can say, ‘We want to record your story.’”

People have talked about their fears for the first time to library staff, describing how they felt they were going to die. “We’ve had people say, ‘Just saying that helped me,’” says Bowling. “That’s one of the side effects of recording their history.” Similarly, when BCPL was able to resume in-school programming, children would open up when asked and talk about what the flood was like for them.

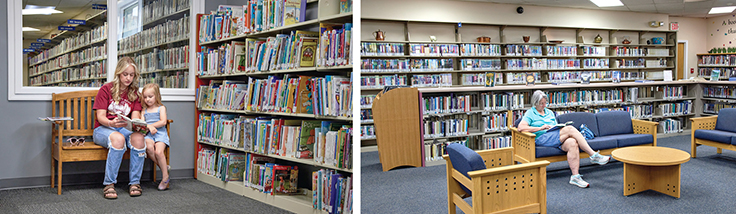

|

|

A PLACE TO REST, READ, PLAY Top row: Resources for young and old at BCPL. Photos ©2023 Bob Hower/Quadrant Inc. Bottom row: Pugh offers story time for young patrons, and (r.) community members of all ages enjoy craft activities at the library. Photos ©2023 Bob Hower/Quadrant Inc. |

FOCUSING ON COMMUNITY NEEDS

As life begins to settle down, BCPL and its board are evaluating the library’s role in Breathitt County’s ongoing recovery. “We’ve looked at ways to open the library more to the community, in disasters and not in disaster times,” says Bowling. “The state of Kentucky requires us to look at our long-term plan every five years, but we’ve pulled that back to a one-year process. We really looked at what we did this year, what worked.”

|

STILL REBUILDING Post-flood reconstruction efforts in Jackson are ongoing. Photo ©2023 Bob Hower/Quadrant Inc. |

The first long-term lesson learned, he notes, “is that we’ve learned to listen more effectively to what the community needs and what the community wants.” Some of those responses surprised Bowling. Though he knew the library’s history and family history center was valued, he was amazed at the number of residents coming in with their cell phones to provide personal photos of the flood, people escaping the water, even the last time they saw their car. “We’re starting to collect those kinds of things,” he says.

Others, he found out, discovered the library in ways they hadn’t before in the wake of the flood, because the library served as a cooling center during the extreme heat of July and August last year. “People would come here and sit and read. We’ve had people tell us, ‘I learned to just sit and be quiet,’” says Bowling. “That’s a long-term thing we didn’t expect.” It’s a form of self-care and a good mental health strategy that people don’t recognize as such, he adds. Some residents are still using the library’s resources and staff to appeal FEMA decisions, or apply for the long-term loans or grants they need for recovery.

In the aftermath of the flood, the library went significantly over budget to stay open. “Our electricity almost tripled. Gas and electric certainly doubled and almost tripled,” Bowling says. Wear and tear on the building increased with the added traffic—mud and water tracked in, spilled food and drink, and continuous use of the bathrooms by a town that had no running water. The Libraries Defying the Odds award will help BCPL restore and improve damaged walls, carpets, tiled floors, and restrooms. “A refresh for this area of the building, a new start, a new coat of paint, new flooring, a new life is what the community needs,” says Pugh.

As the past several years have amply demonstrated, centering the community is BCPL’s top priority. “That’s what we are about,” Bowling adds. “We’re a service agency.” When the worst happened, “we did everything we could.”

Resident Hamblin agrees. During difficult times, BCPL has been “a huge benefit to every single one of us. I love their desire to help people in our community. We have one of the nicest libraries around,” she says. “It’s a blessing for our community.”

Amy Rea is a freelance journalist living in Minnesota.

HONORABLE MENTION

CHARLESTON COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY, SC

ANGELA CRAIG, Executive Director

When COVID-19 amplified disparities across the country, libraries stepped in to help where their communities needed them most. In Charleston County, SC, getting healthy food to people in food-insecure areas was a clear priority. Charleston County Public Library (CCPL) partnered with the local Lowcountry Food Bank to distribute fresh fruit and vegetables, ultimately giving away 13,000 pounds of produce.

But food challenges didn’t end with pandemic shutdowns; in 2021, according to Feeding America’s Mind the Meal Gap study, nearly 33,000 people in the county were living in food insecurity, with the Black population experiencing poorer health than other racial groups in the region. CCPL wanted to help fill community food gaps and also address related health risks, such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes, in an ongoing, sustainable way.

In collaboration with Lowcountry Food Bank and regional health initiative Healthy Tri-County, CCPL developed the Free and Fresh program, which provides free fruits and vegetables at branches in communities with the highest needs. The inaugural Free and Fresh fridge opened in March 2021 at CCPL’s rural St. Paul’s Hollywood Library—where more than 2,000 pounds of produce were distributed in its first 19 weeks. Two more fridges were installed in low-income urban branches. To encourage patrons to use the program and remove any associated stigma, there are no eligibility criteria—anyone is welcome to take produce on a first-come, first-served basis. CCPL ties food literacy into the program, providing recipe handouts and hosting cooking demonstrations and Charlie Cart (small mobile kitchen) programs.

The Duke Endowment provided funds to buy produce for the first year, but in 2022, that funding ended. Closing the program wasn’t an option, CCPL felt, so the library took a new tack: Rather than purchase produce, it would secure in-kind donations. A public awareness campaign was launched to encourage recurring donations of fruits and vegetables from more than 70 community and local nonprofit organizations. Additional grants from local foundations—and the South Carolina Stingrays hockey team—have helped supplement fridge contents during the off growing season. CCPL also developed a partnership with the Charleston Metro Chamber of Commerce to build a community garden at the St. Paul’s Hollywood Library. The library’s outreach department handles the transport and delivery of produce donations, and branch staff are responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of the fridges throughout the week.

Since the program’s launch, CCPL has given away more than 93,000 pounds of produce, and going forward hopes to develop partnerships with local farms and add another fridge location at the Keith Summey North Charleston Library, which is in a low-income and food insecure area. The new library, opened in April 2023, is programmatically centered on food literacy and equipped with a classroom kitchen and a hydroponic garden, making it an excellent candidate. To ensure sustainability, CCPL is currently soliciting more partnerships and donations before launching the new fridge. The program, however, is here to stay. “It’s a blessing!” says one Free and Fresh user. “It helps low-income people and provides healthy food in these critical times when food prices have increased beyond belief.”—Lisa Peet

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!