SDSU Library Detainee Archive Details Migration, Asylum Stories

San Diego State University (SDSU) is currently archiving and digitizing a trove of letters from detainees at the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Otay Mesa Detention Center facility in southern San Diego, 25 miles south of the SDSU campus and less than two miles from the United States–Mexico border. The Otay Mesa Detention Center Detainee Letter Collection is the product of correspondence initiated by members of Detainee Allies, a grassroots group organized in summer 2018 to offer support to refugees arriving from Central America.

San Diego State University (SDSU) is currently archiving and digitizing a trove of letters from detainees at the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Otay Mesa Detention Center facility in southern San Diego, 25 miles south of the SDSU campus and less than two miles from the United States–Mexico border. The Otay Mesa Detention Center Detainee Letter Collection is the product of correspondence initiated by members of Detainee Allies (DA), a grassroots group organized in summer 2018 by Joanna Brooks, SDSU associate vice president for faculty advancement, and Jennifer Gonzalez, a legal communicator with expertise in immigration, along with another half dozen friends and neighbors. Originally known as Otay Allies, the group formed to offer support to refugees arriving from Central America.

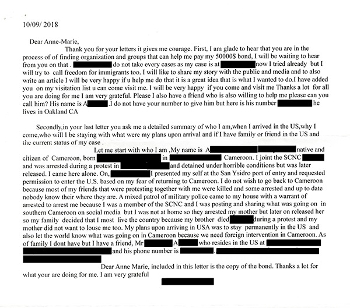

Members of DA began by writing some 30 letters at the end of June to refugees who had arrived from Honduras the month before. About a week later they received more than a dozen letters in return, describing the detainees’ migration stories and living and work conditions. Over the months, DA members exchanged letters with more than 200 people at Otay Mesa, from countries including Afghanistan, Brazil, China, Colombia, Cameroon, El Salvador, Eritrea, Ukraine, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Venezuela.

As of June 2018, 956 people were being held in ICE custody at the facility, which is privately owned by CoreCivic, a company that owns and manages private prisons and detention centers. At least 12 percent of them were asylum seekers, although the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a Syracuse University–based tracker of federal law enforcement data, believes that the number could be higher because of inaccurate information provided by ICE, according to the San Diego Tribune. Many of them had escaped gangs or other violence in their countries of origin. Some had criminal records; others were awaiting appearances in appeals court or deportation.

CONCERNS OF CONFIDENTIALITY

The volume of correspondence eventually swelled to more than 500 letters exchanged between DA members and more than 220 detainees. In fall 2018, Brooks approached SDSU Library interim dean Patrick McCarthy about archiving the collection. He brought the question to university archivist Amanda Lanthorne, who was enthusiastic about the project—and also emphatic about the confidentiality that would be necessary to make these letters public.

“There were numerous conversations about protecting the privacy and safety of the letter writers before we actually accepted the collection and began the digitization process,” Lanthorne said; she eventually helped draft a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with DA that explicitly spelled out the privacy measures the library would take.

For instance, explained Lisa Lamont, head of digital collections and the library’s interim associate dean, they initially considered using letter writers’ first names when they were fairly common, and redacting all last names, small towns, medical conditions, gang affiliations, or names of drug cartels—anything that would make that person identifiable should they be deported back to their hometown, or invite retaliation from a detention center guard.

For instance, explained Lisa Lamont, head of digital collections and the library’s interim associate dean, they initially considered using letter writers’ first names when they were fairly common, and redacting all last names, small towns, medical conditions, gang affiliations, or names of drug cartels—anything that would make that person identifiable should they be deported back to their hometown, or invite retaliation from a detention center guard.

But when Brooks and DA members looked at the database, they felt the use of even first names was too revealing. Instead, SDSU archivists have assigned pseudonyms to each letter writer, using one initial from their name if they’re from one of the more commonly represented countries—Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, or Mexico. If an author is from the Congo or Eritrea, however, their name would be more easily recognizable, so they are listed as Author A, Author B, and so forth.

Their journeys, on the other hand, have been allowed to remain as written, said Lamont. Either they have wound their ways to the United States in such a convoluted way as to be untraceable, or they are dismayingly ubiquitous: “’My family was threatened by the cartel. We had to run. We went to Mexico but we found the cartel was still organized in Mexico. We had to go to the United States. We don’t have anywhere else to go,’” she narrated. “That story is so common that I don't really think you could single anyone out through that.”

Trying to avoid gangs or cartels in their home countries are by far the most common story the letters’ authors write about. Some are escaping volatile political situations, particularly those from African nations. Still others are fleeing LGBTQ+ persecution, domestic violence, rape, torture, or extortion.

Even more than the authors’ origin stories, however, the letters detail what life is like in the detention center, and the process of moving through the U.S. legal system. Conditions are often problematic, and the detainees have documented a range of challenges, including contaminated or insufficient food, unsafe working conditions, medical neglect, lack of access to basic hygiene necessities, forced labor or wage theft, lack of access to legal representation, and prolonged or indefinite detention. “Some of them are expected to show up to their court dates and have their materials in English, and they don't speak English,” noted Lamont.

Many of the letter writers ask for help, or just wish to tell their stories to whomever will bear witness. Often they are simply glad to be in touch with a friendly correspondent. “Thank you for taking the time writing me,” wrote one. “It is truly a pleasure to know that there are still people that care about us!”

A COMPLEX PROCESS

The digital collections team dedicated to the project—Lamont, two full-time staff, two part-time staff, and a student—receives a folder of letters each week, about 20–30 pieces, says Lamont. Many of the correspondents have only written one letter apiece, but some have penned 12 to 14. The workflow involved is painstaking, with most of the team reading each letter to ensure that all the redactions are complete before it is made public. Additional volunteers do everything else, including opening envelopes.

Metadata is attached to each as it is scanned, including a title such as “letter from Author A,” their geographical location—several of the Otay Mesa letter writers were recently sent to a detention center in Alabama—and a one- to two-sentence description in English of the letter’s contents. All team members read at least some Spanish, and at least one person can read each of the other languages represented, so they hope to move on to translations once they’re caught up with digitizing the backlog.

Some 600 letters have been scanned and archived, with more than 200 available to read online. Of the scanned items, however, “A handful will never see the light of day,” Lamont told LJ. “Some of them really do have too much detail, and we won't let those go,” she explained. “If there's too much personal information we just won't let them be public”—at least not until the year 2100, when the MOU specifies that all letters will be made available for research.

On February 1, SDSU student and faculty researchers released a report titled “Testimony from Migrants and Refugees in the Otay Mesa Detention Center.” It was disseminated to a wide general audience, including the California Attorney General and various legislators. At the same time, the first digital copies of the DA correspondence were made available via SDSUnbound, the university’s digital repository, offering access to the letters to students, journalists, researchers, government officials, and the public.

The collection has already been used by several professors on campus for primary source instruction, said Lanthorne, and Google Analytics shows the collection getting traffic from the public. “I've heard from other archivists in the area who are excited about the collection and want to show it to classes that come in for their one-off instruction sessions,” she told LJ. But the collection has particular resonance at SDSU, she noted. “This is happening in our back yard. A lot of our students on campus are DREAMers [alien minors in the United States granted conditional residency].”

In addition, people across the country are getting in touch with SDSU because they want to help. “They either want to write [letters] or they would like to donate, so that commissary money can be given to some of the detainees,” said Lamont—volunteers help deposit donated money into detainees’ commissary account through Western Union. (Letter writers are not allowed to send supplies directly). There is also a donation page on the library’s website to help support digitization efforts, and the team is hoping to apply for some grants.

DA has posted outlines for those who may want to start their own letter-writing group. And although the redaction process for digitization is complicated, said Lamont, “We're happy to consult with any [library] that wants to start archiving in their geographic area too.”

Not only would more detainee archives add to the conversation, she noted, but “it would be interesting to have other archives tell us what works best for them, so that we could all compare notes on how to do this well. If anybody else wanted to jump in on this in their geographic area, we'd be happy to have colleagues.”

Even on their own, though, SDSU and DA are dedicated to keeping the flow of letters going, said Lanthorne. “For many detainees, these letters are the only voice they have. Visitors and nonprofits have been asked to sign [non-disclosure agreements] when visiting detention centers, and many detainees lack the funds to call family or friends. CoreCivic also stopped offering tours of its facilities, so there's really no way to know what's happening inside. The archive is important because it's a way to hear these important but often overlooked stories. It's really been a privilege to work with these materials.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!