Collaborative Collections

Academic librarians struggle with how to meet their users’ need for print collections while coping with limited budgets and expanded demands on their physical space. While resource sharing has a long history in libraries, an approach that treats it as more than an afterthought has potential to reduce both unnecessary duplication and gaps in the collection. Technological advances can help make storage more efficient, faster delivery feasible, and management easier.

|

HIGH DENSITY The ReCAP facility in Princeton, NJ, stores millions of offsite materials for Princeton University, Columbia University, the New York Public Library, and now, Harvard University. |

In academic libraries, collection development is becoming more of a team effort

Academic librarians struggle with how to meet their users’ need for print collections while coping with limited budgets and expanded demands on their physical space. An increasingly popular solution is a growing reliance on shared and consortial collections, by which libraries join together to deliver materials to their patrons efficiently and cost-effectively. While resource sharing has a long history in libraries, an approach that treats it as more than an afterthought has potential to reduce both unnecessary duplication and gaps in the collection. Technological advances can help make storage more efficient, faster delivery feasible, and management easier.

SHARING SPACE

Sharing physical space is perhaps the most straightforward method of bringing collections together. Since 2000, the Research Collections and Preservation Consortium (ReCAP) facility, located in Princeton, NJ, has supported Princeton University, Columbia University, and the New York Public Library (NYPL). Soon, Harvard University will join them. ReCAP is home to almost 15 million items shared among the program’s partners; it fulfills requests for approximately 250,000 items each year. Requests are processed daily and delivered within one or two business days—any request received before 3 p.m. will be out for delivery the next day.

According to Ian Bogus, ReCAP’s executive director, ReCAP’s main philosophy is to facilitate resource sharing with “as low a hurdle and as seamlessly as possible.” Bugus says that unlike interlibrary loan, ReCAP materials are incorporated into partner library catalogs so that “a lot of people aren’t realizing that an item isn’t owned by their home institution until it arrives.” (See LJ’s previous coverage of ReCAP.)

In addition to efficiently delivering a wider array of materials to researchers, ReCAP prioritizes preservation of collection materials, with partners agreeing to retention commitments. One copy of each item in the ReCAP collection must be retained indefinitely. “Our partners wanted to make sure if they were going to rely on someone’s copy, it would remain accessible to them indefinitely,” says Bogus. The ReCAP facility is designed to keep materials physically safe, guarding against threats like fire and humidity, and the facility should have room to grow in its current location.

SHARING COLLECTIONS

Sharing collections doesn’t require a shared facility. The Ivy Plus Libraries Confederation (IPLC) consists of 13 leading academic libraries—at Brown, the University of Chicago, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Duke, Harvard, Johns Hopkins, MIT, Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania (UPenn), Stanford, and Yale—sharing an interlibrary loan network and a mission “to benefit current and future scholars globally” through collaboration and cooperation.

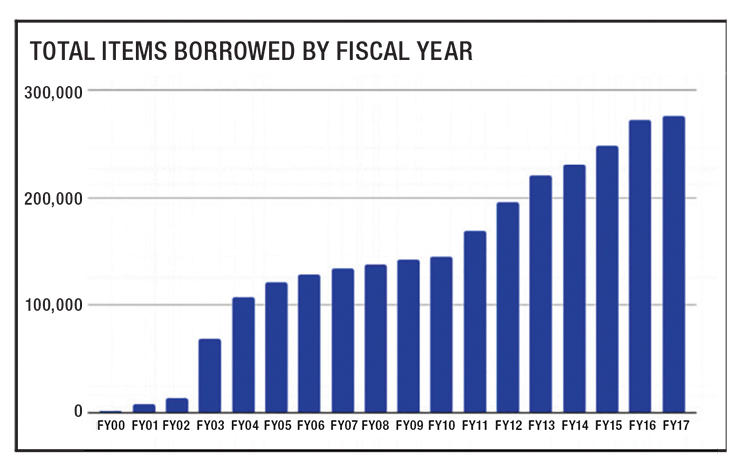

The confederation’s origins go back to BorrowDirect, a resource sharing network started in 1999 with just Columbia, UPenn, and Yale as members. By 2016, all 13 institutions were part of BorrowDirect, the keystone service of IPLC, through which users request approximately 250,000 items per year.

Since 2008, and building on the success of sharing physical collections, the associate university librarians and the directors of collections at IPLC institutions—now known as the Collection Development Group—have met and shared information on how to “collaboratively and cooperatively develop and manage collections,” according to Galadriel Chilton, director of collections initiatives. This builds on grassroots efforts already taking place thanks to librarian connections formed through IPLC and expands these conversations and joint efforts. The IPLC Collection Development Group “embraces a vision for collection development and management which recognizes our preeminent academic research and special collections as one great collection in support of the teaching, research and public missions of our respective institutions and the global scholarly community.”

In addition to collaborative collection development and management, IPLC has a Resource Sharing Group and a Scholarly Communications Task Force focusing on the partnership’s other two strategic priorities, which are “evolving resource sharing and BorrowDirect as well as leadership and advocacy around scholarly communications,” Chilton says, while emphasizing that “the expertise and work of the Technical Services Group, Assessment Group, and Heads of Library IT [are] paramount for the partnership’s success.” She notes that a goal for members is to be “deliberate on what they collect and manage, so these institutions can have the widest variety, as well as intentional duplication where needed” for in-demand resources.

As the IPLC Collection Development Group, the heads of collections at each of these institutions meet in person three times per year, with calls and emails in between. In addition, different groups across the partnership—like music, art and architecture, or Latin American studies librarians—meet and connect over listservs. These subject-specific collaborations expand upon existing collaborative collections and memorandums of understanding, through which librarians coordinate with vendors and with each other to ensure they create broad collections without unnecessary duplication. Chilton explains: “the analogy that I often use for the partnership is one of a flock of migratory birds. Each bird is a unique and individual bird, yet they have made a deliberate choice to fly together.” While acknowledging the unique needs of their scholars and library goals, IPLC partners also recognize their similarities and the fact that if they move forward together, they will be more efficient and effective. Chilton praises the “motivation and vision” of colleagues in the IPLC network, and says they “don’t see a way forward aside from being highly collaborative.”

According to Chilton, “the Collection Development Group is looking at how we build on this network of resource sharing and building a stronger networked collection with intention going forward.” The results are ongoing conversations about collections best practices, and a greater awareness of where libraries should be focusing their budgets and their efforts. In 2018, partner libraries agreed upon plans to work together on collaborative collection development and management, including analysis of holdings, developing tools to support collaborative collections, and continued work on print retention protocols. While this next phase of IPLC is still quite new, Chilton is optimistic that it will make a meaningful difference for researchers.

Currently, users can explore IPLC’s circulating physical collections through BorrowDirect, a separate interface from the libraries’ own catalogs. In addition to collaborative collection development, the top goal of the partnership is developing the ways in which partners share. Chilton noted that IPLC institutions seek to—as her colleague Heidi Nance, director of resource sharing initiatives, says—“evolve the platform and technology so that the shared collection across [IPLC] looks, acts, and feels like one local collection.” Given the great volume of content available, Chilton says, the question is, “How can we make sure users have a unified resource for finding information?”

|

DIRECT SUCCESS BorrowDirect, the keystone service of the Ivy Plus Libraries Confederation, has grown to deliver a quarter of a million items per year. |

PRINT AND DIGITAL PRESERVATION

Beginning in 2008, HathiTrust has been a leader in international collaboration among academic and research libraries and in digital preservation and access. Today, there are 143 HathiTrust members. The HathiTrust Shared Print Program is a new initiative that aims “to ensure preservation of print and digital collections by linking the two, to reduce overall costs of collection management for HathiTrust members, and to catalyze national/continental collective management of collections,” according to Shared Print Program Officer Heather Weltin. The overall goal is to secure a retention commitment for each item in the HathiTrust Digital Library.

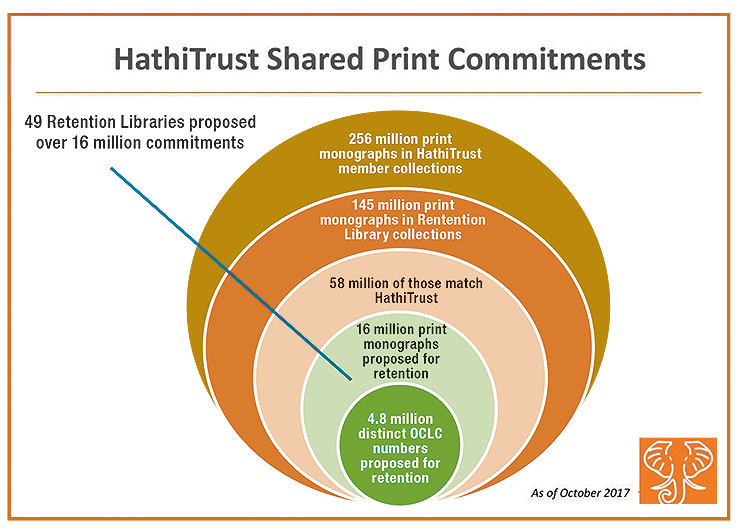

In 2011 HathiTrust members approved a proposal to fund the development of the Shared Print Program, and the program launched its Phase One in 2017. In that phase, 50 member libraries committed to retain over 16 million volumes for 25 years. These volunteer libraries identified the items they wished to retain based on a list of HathiTrust Digital Library items in need of retention commitments. Phase One covered approximately 65 percent of the HathiTrust digital monograph collection. Phase Two, completed in June, secured retention commitments for over 1.5 million monographs, or over 750,000 individual titles. In this phase, the books retained were based on a list developed with OCLC Sustainable Collections Services, representing specific retention commitments needed.

While the first two phases of the Shared Print Program have made enormous strides in retention for the majority of monographs in the Digital Library, the program is encountering a common collection challenge: limited space. Requesting a commitment to retain a significant number of titles for 25 years can be a lot to ask, and so moving into Phase Three, HathiTrust is becoming “more focused” and taking “more factors into consideration with regard to what titles we are asking libraries to retain,” says Weltin. The program is engaging in ongoing conversations with member libraries not currently participating in the Shared Print Program, as well as with current participants, to clarify and evolve priorities. Weltin notes that participating libraries “recognize the value in collectively curating this massive collection that expands upon the holdings in their own academic library, especially a collective collection founded in preservation.”

Currently, preservation efforts focus on circulating materials and on single-part monographs. In the future the Shared Print Program will expand commitments beyond these formats—including for newly digitized materials—and connect with non-retention libraries. The program will also add services for members that will increase access to and discoverability of member collections, and increase communications about retained holdings.

The HathiTrust Shared Print Program is, of course, not the only collaborative initiative seeking to preserve print library collections for the long term. Weltin says: “The biggest change that will likely affect us is the maturity and expansion of other shared print programs and how HathiTrust can continue to work and evolve with them. HathiTrust’s Shared Print Program will remain committed to our founding goals, but I would expect approaches for the program to change in the years to come because of technology or library priorities.”

|

PLANNING FOR PRINT This slide from the HathiTrust Shared Print Program demonstrates what a small fraction of member libraries’ total holdings has been proposed for retention, but the space commitment is still daunting. |

STATEWIDE REPOSITORY

Ohio State University (OSU) is currently leading the charge to create a new major collective collection, which would house print materials in a central repository and preserve them for use throughout Ohio. If the plan is approved by the state this summer, the Ohio Last Copy Repository will expand a central depository in Columbus (one of five state-funded high-density storage facilities hosted by universities in Ohio) to house millions of books.

According to Karla Strieb, associate director, content and access, for OSU Libraries, this plan for large-scale collaboration grows naturally out of the Ohio Library and Information Network (OhioLINK), a network of college and university libraries and the State Library of Ohio. Participating libraries have a history of working together, building a shared catalog, and moving collections around the state. The need to expand the central repository introduced the possibility of creating a collaborative collection and offered an opportunity to use the space to meet not just the needs of OSU, but also of patrons across the state.

Early exploration of the potential for expanding the central depository demonstrated that the plan could be much more efficient and cost-effective than building a brand new space to house shared materials. Strieb notes, “if you want to build an expansion that would house a million volumes, it doesn’t cost twice as much to build a space that accommodates two million. There are economies of scale.” Expanding the current repository also offers benefits beyond outsourcing storage to a vendor, she says, as the library can handle cataloging, digitization, and preservation where needed. “We are a library,” says Strieb. “We don’t just store things. We steward them.”

The Ohio Last Copy Repository would open its doors in approximately two to three years, although it will take some time to finalize a time line and a price tag. If approved, the repository will require communication and collaboration among potential partner libraries to determine what the ongoing relationships among participants will look like. Strieb also describes the “opportunity to look at how [libraries] are taking care of their collections, where they’re locating different parts.” It will provide a chance to develop sustainable and flexible collections.

While the current plan is meant to provide a home for “last copies,” and not just any print materials that participating libraries would like to relocate to high-density storage, future collaboration will also inevitably lead to broader conversations about the ways in which libraries collect and evolve their collections. “It’s interesting to see where things build out,” says Strieb; the structure of the repository and the relationships among the participating libraries are as yet unknown.

Each of these collaborations takes a slightly different approach to shared collections, but they all share common goals: preserving print materials and expanding the amount of content available to patrons. These and other collaborative collection projects are continued works in progress, challenging librarians to harness technology and their own expertise to continue creating the best shared collections possible for the greatest number of libraries and their patrons.

Jennifer A. Dixon is Collection Management Librarian, Maloney Library, Fordham University Law School, New York

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!