Balancing Connections and Collections | Library Design

Making space for users to interact with materials—and one another

It’s a regular day at a regular not-so-quiet library. The tables are full of groups collaborating on projects. All the study rooms are booked solid with small meetings and individuals seeking a quiet refuge. Large gathering spaces are bustling with programs, classes, and community events. More than ever, users crave places to collaborate, interact, build community, and contemplate.

It’s a regular day at a regular not-so-quiet library. The tables are full of groups collaborating on projects. All the study rooms are booked solid with small meetings and individuals seeking a quiet refuge. Large gathering spaces are bustling with programs, classes, and community events. More than ever, users crave places to collaborate, interact, build community, and contemplate.

It’s therefore no surprise that in many types of libraries nationwide, staff are trying to make more space for people. Increasingly, libraries support learning that is social and emotional as well as intellectual, carving out room for Maker spaces, learning commons, flexible spaces, quiet contemplation, and active collaboration. Row upon row of tall bookshelves are not conducive to these emerging uses. “People do not hang out in the stacks,” says Dri Ralph, facilities design coordinator at Washington’s King County Library System (KCLS), who has been involved in 46 library building and renovation projects. Not only is the area for stacks being reduced, what shelves remain are often being lowered to allow for natural light and improved sight lines.

In a 2016 ProQuest survey, 82 percent of academic librarians and 64 percent of public librarians said that “space reclamation” was already or would soon be a priority for their institution. It’s almost a truism that newly constructed or redesigned 21st-century libraries are centered on people rather than, as in the last century, starting with the books.

Yet most of the time, libraries must accomplish this transformation without expanding the building’s footprint. A 2017 LJ survey found that 56 percent of public libraries with a dedicated Maker space converted an existing open area, and 21 percent reduced stacks to make room for it.

At the same time, collections remain essential to libraries’ mission. The flow of newly available print materials is constant and growing. Digitization is a long way from replacing the bulk of library books, if it ever does, and trends back toward print indicate that even where digital versions are available, many patrons will continue to prefer the print version—and that preference may not fade with younger generations, as many once assumed. As shelving is condensed to accommodate other activities, physical collections can become overcrowded and hard to use. Libraries want their collections and learning activities to be partners in creating meaningful learning environments, not rivals. Sometimes it may feel like one or the other gets shortchanged when two essential components of library service compete for limited room. How are successful libraries balancing space for collections and connections?

JUST IN TIME, JUST ENOUGH (L.–r.) King County Library System, WA, fills holds on high-demand titles from off-site storage, freeing up branch copies for browsing. The East Boston Branch, Boston PL, dramatically cut its collection—and circulation soared.

KCLS photo by Steve Albert; East Boston Branch photo by Ty Bellitti

The least expensive and lowest-tech option is to reduce the size of the collection to fit the available shelves. But weeding comes with other challenges: What do you keep, and what do you discard? Will you still have enough materials to meet your patrons’ needs? In addition to the practical problems, heavy weeding can bring up difficult emotions entangled with questions about the library’s identity. How will staff react? Will your community object? Will a space with a smaller collection still feel like a library?

Weeding IN REVERSE

When the East Boston branch of the Boston Public Library (BPL) was built, staff faced this challenge on a large scale. The new building was replacing two underused locations, so both collections had to be merged into a single space. Because the design focused on human interaction and use, shelves were limited. They ran primarily along the perimeter walls, and those that did sit in the middle of the floor were only waist-high.

“Our goals for the branch were to be an inviting space where people can come in and browse the collection, easily access things they want, and have a nice experience with the books they want around them,” says Laura Irmscher, BPL’s chief of collections. To achieve that, her staff began by pulling out obvious low-hanging fruit, such as books in poor condition and duplicates. More consolidation was needed to move from two collections to one.

This is where Irmscher turned the traditional weeding mind-set on its head. Instead of thinking about what to cut, she focused on what to include. Starting with the smaller of the two collections, her team identified what they wanted most, such as currently popular titles or subjects and those trending toward an increase in demand. Next, they considered what new items needed to be added for a fresh, engaging opening day. Finally, they filled in the remaining space with the best of the items left. “It makes the work easier because you’re making positive choices instead of negative ones,” Irmscher says.

The impact of a smaller, better curated collection in a more open and inviting space has been transformational. In the last full year that both of the old branches were open (FY12), their combined circulation was 132,000. In FY16, circulation at the new East Boston building was an astonishing 247,000, making it the system’s busiest branch. With more than one-third of the items checked out at any given time, staff have been able to grow the collection far beyond its actual shelf capacity. As a result, patrons experience high variety in what they see each visit, encouraging even more browsing.

Irmscher reflects that the weeding has revolutionized how people use not just the collection but also the space and services. “We’re just seeing people spending more time there, whether it’s teens hanging out, or people reading in the chairs by the beautiful windows,” she says. “The branch is always full of energy.”

Off-Site Storage

However, some collections just can’t meet user needs and still fit on the public shelves. In that case, off-site storage may be the answer. Costs for this option can vary widely, from depending on a few inexpensive shelves in an existing space to the construction of a brand-new facility such as the fully automated one the New York Public Library (NYPL) recently built under Bryant Park.

Regardless of the scale, extra space is not a silver bullet. Librarians still have important questions to answer: Which items to store, and which to display? How to ensure that patrons still find and request the items stored off-site and get them quickly and reliably and prevent off-site storage turning into a dusty graveyard for unneeded materials?

While a common approach is to move less frequently wanted items off-site, KCLS takes a different tack on some of these questions with its Just in Time collection. Separate from general central storage, this off-site collection of more than 25,000 items holds extra copies of high-interest, popular titles.

In the past, the library ordered large numbers of popular titles to meet the demand for holds. When the holds queue died down, “branches would be flooded with copies,” says Zack Mooney, KCLS collection development and analysis coordinator. Items in good condition would be weeded to make space, only to be reordered six months or a year later to replace lost or damaged copies.

Now each branch receives a manageable number of copies for its shelves, while additional copies are assigned to Just in Time. These off-site copies are the first to fill holds, addressing patron demand while prioritizing local copies for browsing. Branches can also “shop” the collection online to replace local items, quickly procure multiple copies for book groups, create displays, or even provide an entire small, high-interest collection in case of emergency (such as when a patron damaged a branch’s entire biography section N–Z!).

Keeping a high-interest collection fresh takes hands-on management. Staff need to weed frequently to stay current and monitor the ongoing balance between branch and off-site copies. Additional time is required to travel to and from the facility, which itself needs to accommodate multiple uses. Once the initial demand for a resource wanes, sometimes it can be out of sight, out of mind, for both patrons and staff. To be successful, careful choices need to be made about what items will continue to do well when they can only be discovered online.

Just in Time addresses a common tension in public libraries: how to provide access to high-demand titles without overwhelming the space. “It’s a good way to have copies that don’t sit on the shelf,” says Nancy Henkel, KCLS manager of selection and ordering.

Compact Shelving

From hand-crank mobile shelves on the public floor to motorized high-bay stacks in remote storage facilities, compact shelving is an established way to store more books in less space. Yet even this tried-and-true solution is evolving.

No longer relegated to the basement, some modern mobile shelves have sophisticated safety systems and upgraded aesthetics that allow them to be featured in public spaces. Libraries are also turning to this solution for environmental reasons, such as achieving Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design (LEED) certification by helping to shrink the building footprint to lower energy use, or to replace wooden bookshelves not designed to withstand an earthquake as part of a seismic retrofit.

When the historic Hale Library at Kansas State University ran out of shelf space, it had just completed a period-appropriate renovation. Not only did the solution need to work within the existing footprint, it had to honor the historic character of the facility. The library began steadily replacing its stacks with compact mobile shelving. “We calculated that we nearly double our area capacity on every system we add,” says Jean Darbyshire, director of administrative services, in a report from the vendor. The change could be phased in with minimal disruption to users, and custom wood end panels preserve the traditional look and feel. Compared to off-site storage, compact shelving preserves the chance for synergistic browsing on the part of the user, as well as the immediate gratification of self-service.

However, up-front costs for mobile compact shelving can be higher than for traditional stacks. Many of these products require a perfectly level, reinforced floor or foundation. Safety is also a consideration for any shelves that can move, especially if patrons will operate them unsupervised. A variety of infrared beam, sensor, and mechanical emergency stops are available.

Book Bots

Once the stuff of sf, warehouses and fulfillment centers are already sending robots to fetch items out of high-density storage with increasing frequency. While still uncommon in libraries, some large institutions are turning to automation to free up floor space for human interaction. This option doesn’t come cheap; it’s often installed as part of a multimillion-dollar building project. However, some of the costs may be offset by reducing the need for land and minimizing the number of lost items.

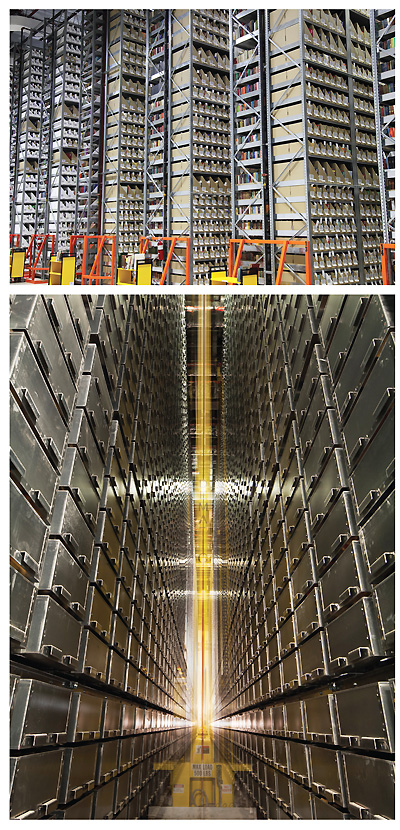

BEHIND THE SCENES (L.–r.) Keep@Downsview preserves a single print copy of low-demand materials in an off-site, high-density, climate-controlled facility for five Canadian universities. The Automated Storage and Retrieval (ASRS) system at the University of Chicago’s Joe and Rita Mansueto Library shelves materials underground by size in 50'-tall racks and can hold 3.5 million volumes in one-seventh the space of conventional stacks.

Downsview photo courtesy of University of Toronto; ASRS Photo by Tom Rossiter, courtesy of the University of Chicago

The Joe and Rika Mansueto Library at the University of Chicago, built in 2011, includes an underground high-density automated storage and retrieval system (ASRS). “The ASRS was selected for its ability to provide rapid access to a rich and growing scholarly collection of materials from disciplines across the university in the heart of campus,” says university librarian and library director Brenda Johnson. A user can request a volume online from anywhere, and the ASRS will pull the book up to the surface to be picked up in the main library.

Johnson touts the many benefits of the system, both for users and for the collection itself. “[The ASRS] speeds scholarly productivity by allowing for the retrieval of materials within an average time of three minutes through use of robotic cranes. It allows us to store collections in one-seventh of the space of regular stacks. It allows us to provide an enhanced environment for preservation of materials, as the temperature of the underground storage area is maintained at 60ºF and the relative humidity at 30 percent.”

As a result of the space the library saved with this system, it was able to create an award-winning building focused on space for study, reading, and online research. The glass-domed structure, designed by Helmut Jahn, prompted one observer to muse that “the library looks like a half-buried crystal Fabergé egg.” Nestled inside is a light-filled 8,000 square foot reading room. The open, human-focused space, Johnson says “is a source of pride for our whole community—faculty, students, and staff.” The much-discussed Hunt Library at North Carolina State University also has a book bot on-site—and allows users to peek at its functioning behind glass.

Shared Storage

Multiple institutions can save floor space by sharing a facility for their off-site collections, while finding that the benefits quickly extend beyond that initial purpose.

Housed at the University of Toronto (UT), Keep@Downsview is a shared print preservation project among UT, the University of Ottawa, Western University, McMaster University, and Queen’s University. “The project is based on the idea that preserving a single ‘shared preservation copy’ of low-demand materials, both serials and monographs, will allow each partner to retain low-demand materials in their collections at lower cost and without crowding storage spaces in the region with multiple copies of lesser used items,” says Caitlin Tillman, associate chief librarian for collections and materials management at UT Libraries. Each partner retains ownership of its items and pays for its space in the high-density, climate-controlled facility.

While a 20-year agreement for a completely new way of sharing space and collections may sound like a radical change, for Tillman it felt like a natural choice. In 2014, her library was planning an expansion of its Downsview preservation facility. At the same time, four nearby universities were looking for ways to expand their preservation capacity. Although none of the five institutions had been involved in a partnership such as this before, they knew of several successful examples and could access some outside funding.

That’s not to say that the realities of sharing spaces and materials were easy. “While we knew it was going to be a big job to match the metadata of five libraries, we didn’t really understand quite how big that job would be and how much staff time would need to be devoted to that work,” Tillman reflects. Completing that step also highlights the work that is still to come. “Since eventually there will be more items off-site than in our largest libraries on campus, we anticipate the need to develop services that make using off-site collections seamless, easy, and part of the research process,” she says. “We are, after all, preserving them so that they do get used.”

WORTH IT ALL

The work is proving to be well worth the effort. To Tillman, one of the greatest benefits is that “the five libraries are now engaged in discussions [of] other potential collaborative collection building efforts.” Keep@Downsview established a foundation for sharing data, space, and processes, which opens the door to a wealth of future partnerships. Other notable shared storage initiatives include ReCAP, jointly owned and operated by Columbia University, NYPL, and Princeton University and located on Princeton’s Forrestal Campus, and the Five College Library Repository Collection (FCLRC), a set of lesser-used materials drawn from the libraries of Amherst College, Hampshire College, Mount Holyoke College, Smith College, and the University of Massachusetts. The latter opened a new library annex building in May.

Libraries of all types are feeling the push and pull of multiple demands on a limited amount of space. The places increasingly carved out for active learning and collaboration sometimes come at the expense of the shelves that held physical collections. Taking a creative strategic approach to managing collections and considering the full spectrum of alternatives can help alleviate, if not eliminate, this tension. Each solution comes with unique benefits and challenges, and none are one size fits all. Yet with some out-of-the-stacks thinking, all can fit enough collections, and connections, for their communities.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!