Great Outdoor Spaces | Library Design

Promote learning, wellness, environmental benefits, and economic opportunity for patrons and communities outside

The best libraries don’t stop at the front door. Gardens and green roofs alike are beautiful and inspiring. The benefits of exposure to nature are much more than cosmetic: for individuals, research has related it to reduced stress, inflammation, and mortality; improved memory, job satisfaction, and eyesight; and greater social capital. For communities, successful public outdoor spaces not only improve the physical and mental health of residents, they have been shown to aid the environment, create a stronger sense of community, and even boost the economy.

The best libraries don’t stop at the front door. Gardens and green roofs alike are beautiful and inspiring. The benefits of exposure to nature are much more than cosmetic: for individuals, research has related it to reduced stress, inflammation, and mortality; improved memory, job satisfaction, and eyesight; and greater social capital. For communities, successful public outdoor spaces not only improve the physical and mental health of residents, they have been shown to aid the environment, create a stronger sense of community, and even boost the economy.

When libraries get involved in developing them—whether gardens, parks, or plazas—they can become places of rich engagement, learning, and community celebration: witness the example of a pioneering system like Colorado’s Anythink and LJ’s 2014 Best Small Library in America Pine River. Following in those footsteps, a variety of recent projects and initiatives illustrate how libraries are using outdoor spaces to promote literacy, celebrate diversity, and bolster economic development within their communities, says Susan Benton, CEO of the Urban Libraries Council (ULC). Fostering gardens and other outdoor spaces, she says, are part of how libraries can lay “the foundation for something someone will take forward with them and be stronger” for it.

Petals, pollen—and partners

It all started with bees and butterflies. In Princeton, IL, there is now a constellation of library-supported pollinator gardens citywide. In 2014, Ellen Starr, a biologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service, reached out to the city to consider hosting a garden on public grounds. She connected with the Princeton Public Library (PPL) with impressive results. The resulting garden “complements our vision,” says PPL director Julie Wayland. “Our patrons in many instances look to us to provide a forum for what is happening in the community. We work closely with our city government, local groups, and community organizations to provide an opportunity for them to expound on any programs or projects [on which] they are working. In this way we feel we are providing an educational benefit to the community.”

LEARNING IN BLOOM Top: the pollinator garden in Princeton, IL, supports ecology and education; a Little Free Library in the garden at the Princeton PL encourages visitors to read outside (inset). Middle: the Read and Feed Teaching and Demonstration Garden, Colonial Heights Library, Sacramento, CA, teaches food literacy and healthy eating. Bottom: the East Baton Rouge Parish Library Main Library at Goodwood, LA, features bioswales, which remove pollution from water runoff while highlighting the landscape.

Princeton photos vourtesy of Princeton PL; Colonial Heights photo courtesy of Sacramento PL

The garden is lush with a well-kept path, winding through bushes with striking yellow, red, and purple flowers. It serves as a thriving outdoor classroom. The library has used the garden as a catalyst to connect with additional community partners: along with the city and the USDA, the library has collaborated with Voices from the Prairie, a local think tank, and the Illinois Clean Energy Community Foundation. Together they have developed an array of programs, initiatives, and activities for residents of all ages.

This past Earth Day, the library unveiled a second pollinator garden on the other side of town, focused on butterflies. (Each garden has a Little Free Library managed by PPL.) This garden sits at the site of a center serving people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Wayland says that it has been a great reflection of Princeton and its people, who are “involved in the beautification of the city” and “have dedicated time and effort to maintaining the historical homes and buildings in town.” The library, and its garden, is one of the first buildings seen when entering the city from the east. It “sets the tone” and serves to emphasize how important maintaining insect populations are in a changing environment. Local gardeners volunteer their time to maintain the garden and share their expertise with other community members who visit. “They know how important honeybees are to our environment and the effect of the decline of their population,” says Wayland.

Learning, naturally

When librarians at the Middle Country Public Library (MCPL), in Centereach and Selden, NY, began a collaboration with the Long Island Nature Collaborative for Kids (LINCK) to think about how to support nature-based education, the result was a transformative program and space called the Nature Explorium. It’s an outdoor environment designed to connect literacy, active learning, and an appreciation for nature. Library staff were introduced to the idea of creating “nature explore classrooms” through a workshop organized by the Dimensions Educational Research Foundation, a nonprofit whose work introduces children to nature through meaningful connections. “It was during this session that we had the idea that libraries—in addition to child-care centers, youth centers, churches, schools—could provide another community place for outdoor classrooms,” says Tracy LaStella, assistant director for youth services at MCPL.

The library followed the introductory workshop with a two-day training session that brought together landscape architects, library staff, and LINCK members to imagine and begin to design the Nature Explorium. In June 2010, the space, designed with expertise from the U.S. Forest Service, opened to the public.

The Nature Explorium isn’t simply a garden, it’s a multisensory outdoor learning environment with planted spaces, paths, an outdoor stage, and play sets featuring a variety of themes and designed for patrons of a variety of ages to interact with one another and library resources. It provides a striking, playful, and inviting example of the concept of placemaking. By creating spaces that maximize shared value and strengthen connections between people and place, placemaking emphasizes the sociability, variety of uses, access, connections, and comfort in physical, publicly accessible areas within towns, cities, or communities.

The Nature Explorium illustrates maximized shared value in a variety of compelling ways. Bright colors pop from both the built and natural environment in the space. Garden beds are appropriately sized for children of all ages, and a “build it” station hosts wooden blocks to spark the imagination. A “read it” station offers space for both formal and informal story times.

PARTNERS WITH PERSPECTIVE

An advisory committee, composed of members from the local school district, gardening experts, and local and national nonprofits, helps to create programming for the space. “Partnering with other organizations broadens our perspective, helps change the image of the library, integrates the library into the larger community of similar interests, and, over the years, has helped us to transform into a dynamic community center,” LaStella says.

The Nature Explorium offers a choice of activities that ranges from unstructured play and reading a book with a caregiver to deep, sustained learning experiences. Programming doesn’t only cover topics on the environment or sustainability. The library has created opportunities for community members to collaborate on art projects, such as “Crochet It! A Creative Community Project.” Over the summer of 2017, local artist Carol Hummel led a community-focused crochet project, featuring instructional workshops, kits, and over 200 volunteers participating in the art installation. Thousands of colorful crocheted circles wrapped around trees will culminate in two unique art pieces completed in time for September’s dedication ceremony honoring the space, volunteers, and artists’ vision. The Nature Explorium will host the exhibit.

MORE TO EXPLORE The Nature Explorium at the Middle Country Public Library in Centereach and Selden, NY, offers a range of activities, including unstructured outdoor active play at the Play It stage (top), water learning (and fun) in the Splash It area (bottom l.), and more traditional library offerings such as story times held in the Read It space (bottom r.).

Photos by Dutch Huff Photography

The “Gardening Crew” is a program that partners youth grades five to nine with master gardeners and educators to grow vegetables at both the Nature Explorium and Hobbs, a local community farm. According to LaStella, this is a “multisensory educational [experience] related to basic gardening and nutrition as part of a service learning project that benefits the local community. [Much] of the produce grown at the farm is donated to local food pantries.” During part of the programming, families and K–2 children work alongside the crew to harvest vegetables, tasting them along the way and taking some home.

Food for thought

Gardening or otherwise interacting with biodiversity provides a powerful vehicle for other forms of literacy or library resources and expertise. Seed collections and exchanges, in public libraries from Nashville to the Florida Department of State’s Division of Library and Information Services, “create community [and] teach nourishment and help people understand [how] to grow their own food. It’s a win-win for the library and the community,” ULC’s Benton says.

In urban settings, programs that connect gardens, biodiversity, and health and wellness are showing just how effectively libraries can create, support, and catalyze healthy and sustainable communities, with what Benton calls “agility and practiced engagement.” The Read and Feed Teaching and Demonstration Garden at the Colonial Heights Library is located in South Sacramento, CA. It emphasizes nutrition, healthy choices, and service learning through its garden and is a key partner in the area’s Building Healthy Communities initiative. The raised, waist-high beds were built by more than 600 volunteers of all ages, and the garden serves to strengthen nutritional literacy and access to healthy food in an urban environment classified as a food desert.

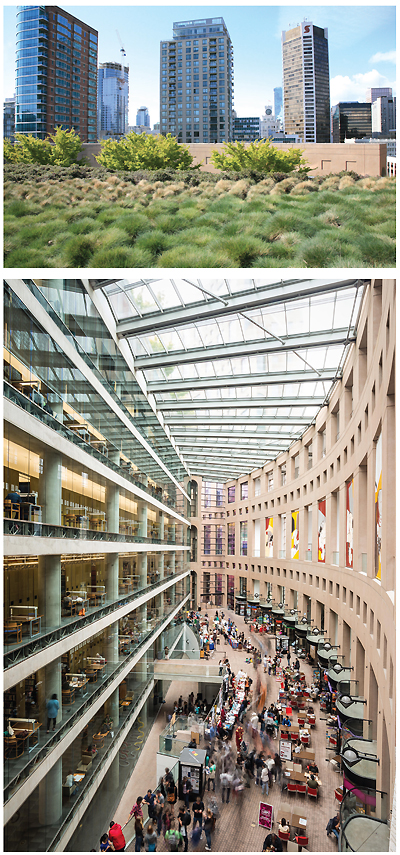

TOP PRIORITY The main branch of the Vancouver Public Library, BC, features a green roof with multiple plantings (top). The atrium bridges indoors and out with abundant natural light, even before renovation adds still more outdoor access to the building (bottom).

Top photo courtesy of Vancouver Pl; Bottom photo by Paul Joseph

Sustainable connections

When libraries have the opportunity to renovate or build new, they can create settings that connect the library to its environment functionally as well as aesthetically and connect patrons both to nature and to one another. The East Baton Rouge Parish Library (EBRPL) Main Library at Goodwood, LA, one of LJ’s 2015 New Landmark Libraries, is sited within a park, connecting visitors to natural light, fresh air, biodiversity, and community. The outdoor plaza links the library to the Baton Rouge Parks and Recreation Commission teaching building, which hosts a small collection of library resources. By using flora- and fauna-inspired fabrics and designs, the library thematically brings the outdoors in and celebrates its location. By situating the building within the park, the library helps to make the park that much more convenient, walkable, and useful. It complements the park with its own great outdoor spaces, from the plaza to the parking lot.

EBRPL features bioswales, which resemble miniature gardens in and around the parking areas and the building site. In reality, they’re landscaped elements that can remove or concentrate pollution from water runoff. Often planted with vegetation, bioswales also soften the contours and features of the built infrastructure. Many people don’t even realize the swales’ functionality, though they notice their beauty.

Outdoor spaces can combine natural and built elements that draw people to the site, encourage them to connect with each other, and provide a variety of functions. The largest capital project for the City of Vancouver, BC, at the time, the Library Square and the central branch, designed by world-renowned architect Moshe Safdie, opened in 1995. The Library Square is an exemplar of great outdoor (and indoor) spaces that serve to support community members whether they are accessing library resources, meeting over coffee, shopping, or using city services.

A true piazza, the two plazas offer both urban outdoor space with café seating and horizontal platforms for people to congregate. The library also features a multifunctional green roof, visible from the upper floors of the Library Square. By planting regional grasses in different colors and flowing patterns, the roof becomes a painting-like interpretation of the region’s natural resources: the forest, the Fraser River, and the shoreline. The grasses are tough and drought-resistant and help offset what are known as “heat islands” often present in dense urban areas with plenty of concrete and hard surfaces. Finally, the roof is fundamentally functional, providing habitats for birds, bees, and butterflies. Vancouver Public Library is about to add even more outdoor space in its current renovation of the two top floors. Scheduled for completion in spring 2018, the work will open more space to the public and include a garden high above the plazas where people can gather.

From pollinator gardens to massive urban plazas, green roofs to bioswales, libraries all across North America excel at developing and maintaining great outdoor spaces. These not only serve as beautiful examples of our natural landscape but offer ways for libraries and their partners to invest in the health and wellness of communities, connect residents to library resources, and enhance literacies. Great outdoor spaces provide opportunities for libraries to showcase their capacity to strengthen communities and be true placemakers—inside and out.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!