Careers During COVID: Placements and Salaries Survey 2021

2020 LIS graduates faced a dip in salaries, an increase in remote work, and a drop in satisfaction, but not a major rise in unemployment.

2020 LIS graduates faced a dip in salaries, an increase in remote work, and a drop in satisfaction, but not a major rise in unemployment

2020 LIS graduates faced a dip in salaries, an increase in remote work, and a drop in satisfaction, but not a major rise in unemployment

Library Journal ’s annual Placements and Salaries survey tells the story of 2020 LIS graduates as they searched for and began their professional positions in a most challenging and unusual year. First, we express our support and appreciation for the members of the LIS professional and education community for their hard work and dedication to deliver vital information services and education as our patrons and students faced incredible hardships. We also send our sympathy to all who have suffered illness or the loss of family, friends, and colleagues during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thanks to all the graduates who were able to participate in this year’s survey.

LIS graduates in 2020 bore the full force of the COVID-19 pandemic as they sought employment or career advancement. Following the national shutdown, fewer new positions were posted and some job offers were rescinded. Many employers developed modifications to working environments and processes to allow employees to perform their duties more safely, involving online interaction, social distancing, protective clothing, environmental changes, and frequent testing. Institutions like libraries and schools were subject to adaptations that reflected and varied with the epidemiological status of their communities. For many, this meant substantial alteration of their services and closures for varied lengths of time. These necessarily impacted the organizations’ hiring decisions, as well as prospective employees’ perceptions of their career options. We added some pandemic related questions to the survey to better understand the impact on 2020 graduates.

|

TABLE 1: STATUS OF 2020 GRADUATES* |

|||||||

| School Region | Number of Schools Reporting | Number of Graduates Responding | Employed in LIS field | Employed outside of LIS | Currently Unemployed or Continuing Education | Total Answering | % employed full-time |

| Midwest | 10 | 1,403 | 302 | 101 | 40 | 443 | 87% |

| Northeast | 8 | 902 | 159 | 34 | 23 | 216 | 78% |

| South Central | 7 | 920 | 132 | 23 | 7 | 162 | 88% |

| Southeast | 6 | 473 | 165 | 38 | 21 | 224 | 92% |

| West (Pacific/Mountain) | 5 | 818 | 165 | 30 | 24 | 219 | 69% |

| TOTAL | 36 | 4,516 | 923 | 226 | 115 | 1,264 | 84% |

|

*If currently employed |

|||||||

Highlights from the findings include:

• Starting salary levels dipped but didn’t plunge.

• Most employed 2020 graduates landed full-time, permanent positions. Despite COVID-19, unemployment rose only slightly over 2019.

• Gender-based salary disparity showed modest improvement, reversing last year’s negative trend.

• Job-seekers were more conservative this year in their employment decisions: more likely to stay with their current job or employer, and less likely to relocate for a new job.Howeverk, they were more likely to apply to jobs out of their area if remote work was an option.

• Most LIS schools had to make fewer changes than they had anticipated to continue to support their graduates’ job searches.

Thirty-six the U.S.-based American Library Association (ALA) accredited schools participated in this survey. These schools reported awarding degrees to a total of 4,516 graduates, an increase of almost 6 percent over last year. Twenty-eight percent of these 2020 graduates completed the survey, an increase of 2 percent over 2019.

Holding true to the usual pattern in the LIS field, most respondents described themselves as female (77 percent). The proportion of male graduates (18 percent) decreased slightly over the prior two years (19 percent in 2019 and 20 percent in 2018). Nonbinary/gender nonconforming respondents comprised 3.1 percent of those who took the LJ survey. Some .4 percent chose other and. 9 percent declined to answer. Together, these responses from those with genders not on the binary showed a small increase over the prior two years. Schools that conducted their own research and shared the results reported .3 percent nonbinary students and 5.6 percent other or unsure. Because the sample size for nonbinary respondents and those who chose other or decline to answer is too small to yield statistically significant results when compared to the placements and salaries of other genders, gender comparisons shown in the tables are male to female only.

|

TABLE 2: PLACEMENTS & FULL-TIME SALARIES OF 2020 GRADUATES BY REGION |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Placement Region | Number of Placements | NO. RESPONDING | LOW SALARY | HIGH SALARY | AVERAGE SALARY | DIF IN AVG M/F SALARY† | MEDIAN SALARY | |||||||||||||

| Women | Men | Nonbinary* | All | Women | Men | Nonbinary* | Women | Men | Nonbinary* | Women | Men | Nonbinary* | All | Women | Men | Nonbinary* | All | |||

| Midwest | 292 | 105 | 38 | 4 | 151 | $20,000 | $28,800 | $40,000 | $102,500 | $137,500 | $57,500 | $56,007 | $64,693 | $50,125 | $57,772 | 13.43% | $52,000 | $64,000 | $51,500 | $52,500 |

| Mountain | 65 | 26 | 6 | 1 | 34 | 30,000 | 30,500 | 40,000 | 107,500 | 54,000 | 40,000 | 48,500 | 44,840 | 40,000 | 47,795 | -8.16% | 45,798 | 45,850 | 40,000 | 45,798 |

| Northeast | 190 | 80 | 17 | 5 | 103 | 26,000 | 34,000 | 38,000 | 132,500 | 125,000 | 67,000 | 59,067 | 62,193 | 49,322 | 59,265 | 5.03% | 54,958 | 50,000 | 47,650 | 54,000 |

| Pacific | 155 | 41 | 13 | 4 | 78 | 38,121 | 38,000 | 35,000 | 142,500 | 132,500 | 67,000 | 77,442 | 80,749 | 50,500 | 70,729 | 4.10% | 70,000 | 82,500 | 50,000 | 64,717 |

| South Central | 129 | 79 | 12 | 4 | 95 | 19,000 | 38,000 | 29,000 | 92,500 | 117,500 | 42,000 | 47,283 | 54,246 | 36,677 | 47,716 | 12.84% | 45,000 | 51,600 | 37,854 | 45,000 |

| Southeast | 219 | 90 | 18 | 6 | 120 | 27,000 | 33,000 | 28,000 | 98,000 | 144,000 | 63,151 | 51,205 | 62,074 | 43,859 | 52,866 | 17.51% | 49,800 | 51,500 | 44,500 | 50,000 |

| International | 18 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 40,000 | 55,000 | n/a | 75,000 | 55,000 | n/a | 56,875 | 55,000 | n/a | 56,500 | -3.41% | 56,250 | 55,000 | n/a | 55,000 |

| Remote | 7 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 42,000 | 62,000 | n/a | 60,000 | 62,000 | n/a | 51,000 | 62,000 | n/a | 54,667 | 17.74% | 51,000 | 62,000 | n/a | 60,000 |

| TOTAL | 1,075 | 436 | 106 | 24 | 598 | 19,000 | 28,800 | 28,000 | 142,500 | 144,000 | 67,000 | 55,461 | 63,393 | 45,790 | 56,453 | 12.51% | 50,073 | 53,500 | 45,000 | 51,000 |

|

This table represents only salaries reported as full-time. Some data were reported as aggregate without breakdown by gender or region. Comparison with other tables may show different number of placements. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

*Includes nonbinary, other, and declined to answer gender. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

†The nonbinary sample is too small to yield statistically significant results when compared to placements and salaries of other genders. Therefore, all gender comparisons shown are male to female only. |

||||||||||||||||||||

The 2020 graduates’ race/ethnicity revealed changes in proportions compared to last year. White/non-Hispanic representation rose slightly (83 percent) for the third year in a row. Black/African American representation (8 percent) and that of Asian/Pacific Islanders (6 percent) both doubled versus last year. Very few graduates identified as Native Alaskan/American Indian (less than 1 percent) or another race (3 percent). On a separate measure, representation of Hispanic/Latinx graduates (1 percent) was twice as large as in 2019.

The 2020 graduates’ race/ethnicity revealed changes in proportions compared to last year. White/non-Hispanic representation rose slightly (83 percent) for the third year in a row. Black/African American representation (8 percent) and that of Asian/Pacific Islanders (6 percent) both doubled versus last year. Very few graduates identified as Native Alaskan/American Indian (less than 1 percent) or another race (3 percent). On a separate measure, representation of Hispanic/Latinx graduates (1 percent) was twice as large as in 2019.

The age distribution across 2020 graduates was slightly older than the prior year. Over half of respondents said they were between 26 and 35 years old (54 percent), yielding an average age of 35, skewing a bit older than 2019 (58 percent and an average age of 34). Still, most graduates were 35 or under (66 percent vs. 69 percent in 2019), and 16 percent were over 45 (up from 13 percent). Current graduates were evenly split between those pursuing a first career and those who had prior professions; the proportion of first career grads declined for the third year in a row.

PLACEMENTS AND SALARIES

The average full-time starting salary for 2020 graduates was $56,453. This figure represents a decrease of 3.75 percent from the average for 2019, and unfortunately breaks a seven-year streak in which the average salary increased each year. To maintain perspective, however, it is important to note that the 2020 average salary is still higher than all other average salaries for the previous nine years. Despite COVID-related employment issues such as hiring freezes, layoffs, and shutdowns, 2020’s average LIS starting salary did not plummet. Employed 2020 graduates enjoyed high levels of full-time employment (84 percent, only a small dip from 2019 levels (86 percent). As with last year, full-time employed graduates overwhelmingly held permanent positions (94 percent) rather than temporary ones (6 percent).

In the extraordinarily difficult year that 2020 was for job seekers in all fields, the unemployment rate among LIS graduates was up, but only slightly (9 percent, versus 8 percent in 2019). Among the unemployed, three-fourths were actively seeking employment in the LIS field. Others cited educational reasons for not hunting for a job, as students enrolled in further study (17 percent) or took positions as interns (3 percent). There were upticks in graduates’ taking time off for personal reasons (10 percent versus 4 percent in 2019), or being furloughed from their jobs (3 percent) and it seems likely that these were influenced by the pandemic.

The majority of 2020 graduates employed part-time hold only one position (64 percent) and the average number of positions held (1.4) is unchanged from 2019. However, holding multiple jobs appears more prevalent for 2020 graduates. While part-time employment (16 percent) is up only slightly from 2019 (14 percent), the 2020 increase derives from a few more graduates’ holding two part-time jobs (30 percent as compared to 28 percent in 2019). Six percent of part-timers reported that they hold three or more positions. Nearly a fifth, 17 percent, of 2020 graduates employed ful- time also have a second or third job. Among these moonlighters, 51 percent have other jobs unrelated to LIS or education. Financial concerns are a motivation for moonlighting: 28 percent of full-time employed graduates with $50,000 or more in student loan debt hold second or third jobs.

| TABLE 4: PLACEMENTS BY FULL-TIME SALARY OF REPORTING 2020 GRADUATES | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AVERAGE SALARY | MEDIAN SALARY | LOW SALARY | HIGH SALARY | PLACEMENTS | Total Placements | |||||||||||||||

| Schools | Women | Men | Nonbinary** | All | Women | Men | Nonbinary** | All | Women | Men | Nonbinary** | All | Women | Men | Nonbinary** | All | Women | Men | Nonbinary** | |

| Alabama | $33,942 | $84,000 | $42,000 | $43,628 | $36,883 | $84,000 | $42,000 | $38,500 | $23,000 | $84,000 | $42,000 | $23,000 | $39,000 | $84,000 | $42,000 | $84,000 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Arizona | 51,524 | 44,350 | - | 50,567 | 48,000 | 44,350 | - | 47,000 | 35,000 | 41,700 | - | 35,000 | 80,000 | 47,000 | - | 80,000 | 13 | 2 | - | 15 |

| Buffalo | 49,743 | 60,574 | - | 51,097 | 48,000 | 60,574 | - | 50,000 | 40,000 | 60,574 | - | 40,000 | 70,000 | 60,574 | - | 70,000 | 7 | 1 | - | 8 |

| Catholic* | 52,163 | 50,000 | - | 51,923 | 54,648 | 50,000 | - | 54,295 | 27,000 | 50,000 | - | 27,000 | 75,010 | 50,000 | - | 75,010 | 8 | 1 | - | 9 |

| Clarion | 47,061 | - | 40,000 | 46,355 | 45,000 | - | 40,000 | 44,500 | 30,500 | - | 40,000 | 30,500 | 72,000 | - | 40,000 | 72,000 | 9 | - | 1 | 10 |

| East Carolina | 44,625 | 51,000 | - | 45,900 | 46,250 | 51,000 | - | 49,500 | 27,000 | 51,000 | - | 27,000 | 59,000 | 51,000 | - | 59,000 | 4 | 1 | - | 5 |

| Emporia State | 46,367 | 51,841 | - | 46,865 | 46,500 | 51,841 | - | 50,000 | 35,000 | 51,841 | - | 35,000 | 62,000 | 51,841 | - | 62,000 | 10 | 1 | - | 11 |

| Hawaii Manoa | 53,000 | 46,500 | 50,000 | 50,625 | 52,500 | 46,500 | 50,000 | 50,000 | 47,000 | 38,000 | 50,000 | 38,000 | 60,000 | 55,000 | 50,000 | 60,000 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| Illinois Urbana-Champaign | 49,405 | 55,000 | - | 50,027 | 52,500 | 55,000 | - | 52,500 | 20,000 | 45,000 | - | 20,000 | 70,710 | 65,000 | - | 70,710 | 16 | 2 | - | 18 |

| Indiana Bloomington* | 57,131 | 50,661 | - | 54,467 | 52,250 | 40,000 | - | 52,000 | 33,000 | 30,500 | - | 30,500 | 98,000 | 75,000 | - | 98,000 | 10 | 7 | - | 17 |

| Indiana Purdue | 54,578 | 53,438 | - | 54,293 | 48,250 | 46,125 | - | 48,250 | 37,440 | 33,000 | - | 33,000 | 84,000 | 88,500 | - | 88,500 | 12 | 4 | - | 16 |

| Kent State* | 40,786 | 39,000 | - | 40,389 | 40,000 | 39,000 | - | 40,000 | 24,000 | 30,000 | - | 24,000 | 65,500 | 48,000 | - | 65,500 | 7 | 2 | - | 9 |

| Kentucky | 43,485 | 71,333 | - | 47,464 | 42,000 | 47,000 | - | 43,000 | 20,893 | 42,000 | - | 20,893 | 69,000 | 125,000 | - | 125,000 | 18 | 3 | - | 21 |

| Long Island | 72,000 | - | - | 72,000 | 64,500 | - | - | 64,500 | 51,000 | - | - | 51,000 | 108,000 | - | - | 108,000 | 4 | - | - | 4 |

| Maryland | 54,158 | 84,667 | 44,000 | 59,244 | 52,500 | 57,000 | 44,000 | 53,500 | 38,121 | 53,000 | 44,000 | 38,121 | 75,500 | 144,000 | 44,000 | 144,000 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 16 |

| Michigan* | 87,500 | 89,643 | 57,500 | 87,853 | 85,000 | 87,500 | 57,500 | 87,500 | 37,500 | 37,500 | 57,500 | 37,500 | 142,500 | 137,500 | 57,500 | 142,500 | 56 | 28 | 1 | 85 |

| NC Chapel Hill* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| NC Greensboro | 48,804 | 39,667 | 51,000 | 47,521 | 45,000 | 39,000 | 51,000 | 44,500 | 31,600 | 33,000 | 51,000 | 31,600 | 95,000 | 48,000 | 51,000 | 95,000 | 34 | 6 | 1 | 41 |

| North Texas | 51,715 | 55,000 | 33,854 | 50,095 | 50,500 | 55,000 | 33,854 | 50,500 | 38,500 | 54,000 | 29,000 | 29,000 | 70,000 | 56,000 | 38,708 | 70,000 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Oklahoma | 57,500 | 53,000 | 37,000 | 51,250 | 57,500 | 53,000 | 37,000 | 49,000 | 45,000 | 53,000 | 37,000 | 37,000 | 70,000 | 53,000 | 37,000 | 70,000 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Pratt | 72,500 | 62,000 | 51,000 | 61,800 | 72,500 | 62,000 | 51,000 | 62,000 | 50,000 | 62,000 | 35,000 | 35,000 | 95,000 | 62,000 | 67,000 | 95,000 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Rutgers | 60,074 | 57,500 | 48,960 | 59,449 | 55,000 | 57,500 | 48,960 | 54,982 | 33,000 | 50,000 | 48,960 | 33,000 | 119,000 | 65,000 | 48,960 | 119,000 | 23 | 2 | 1 | 26 |

| San Jose* | 54,486 | 52,971 | 45,000 | 53,713 | 53,500 | 45,000 | 45,000 | 50,000 | 32,000 | 28,800 | 45,000 | 28,800 | 80,000 | 95,000 | 45,000 | 95,000 | 18 | 7 | 1 | 26 |

| Simmons | 51,114 | 45,550 | 59,267 | 51,179 | 48,000 | 46,350 | 63,151 | 48,000 | 35,000 | 40,000 | 47,650 | 35,000 | 73,000 | 49,500 | 67,000 | 73,000 | 27 | 4 | 3 | 34 |

| Southern California | 60,000 | 55,000 | - | 58,000 | 52,000 | 55,000 | - | 52,000 | 48,000 | 40,000 | - | 40,000 | 80,000 | 70,000 | - | 80,000 | 3 | 2 | - | 5 |

| Southern Mississippi | 44,013 | 53,000 | - | 44,575 | 43,000 | 53,000 | - | 43,350 | 25,000 | 53,000 | - | 25,000 | 91,772 | 53,000 | - | 91,772 | 15 | 1 | - | 16 |

| St. Catherine | 51,410 | - | - | 50,175 | 48,000 | - | - | 46,500 | 39,000 | - | - | 39,000 | 63,000 | - | - | 63,000 | 5 | - | - | 6 |

| St. John's | 62,088 | - | 38,000 | 59,411 | 61,350 | - | 38,000 | 56,700 | 36,000 | - | 38,000 | 36,000 | 90,000 | - | 38,000 | 90,000 | 8 | - | 1 | 9 |

| Syracuse | 53,000 | 35,000 | - | 47,000 | 53,000 | 35,000 | - | 35,000 | 26,000 | 35,000 | - | 26,000 | 80,000 | 35,000 | - | 80,000 | 2 | 1 | - | 3 |

| Tennessee | 42,112 | 43,733 | 28,000 | 41,451 | 42,000 | 41,000 | 28,000 | 41,500 | 27,000 | 40,000 | 28,000 | 27,000 | 58,000 | 50,200 | 28,000 | 58,000 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 14 |

| Texas Women's | 48,869 | 48,667 | - | 48,851 | 51,000 | 54,000 | - | 51,000 | 21,000 | 38,000 | - | 21,000 | 65,000 | 54,000 | - | 65,000 | 30 | 3 | - | 33 |

| Valdosta | 50,642 | 55,048 | 32,000 | 50,830 | 45,500 | 52,000 | 32,000 | 45,620 | 29,000 | 45,000 | 32,000 | 29,000 | 100,000 | 78,000 | 32,000 | 100,000 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 18 |

| Washington* | - | - | - | 55,323 | - | - | - | 55,000 | - | - | - | 19,999 | - | - | - | 85,000 | - | - | - | 31 |

| Wayne State | 55,583 | 74,602 | 44,667 | 57,646 | 50,999 | 81,000 | 45,000 | 49,998 | 25,000 | 46,406 | 40,000 | 25,000 | 100,279 | 90,000 | 49,000 | 100,279 | 14 | 4 | 3 | 21 |

| Wisconsin Madison | 44,017 | - | 54,000 | 44,683 | 41,500 | - | 54,000 | 42,000 | 38,091 | - | 54,000 | 38,091 | 54,000 | - | 54,000 | 54,000 | 14 | - | 1 | 15 |

| Wisconsin Milwaukee | 48,249 | 54,389 | - | 50,705 | 48,775 | 52,000 | - | 52,000 | 19,000 | 40,000 | - | 19,000 | 70,000 | 75,000 | - | 75,000 | 9 | 6 | - | 15 |

| Total | 55,461 | 63,393 | 45,790 | 56,453 | 50,073 | 53,500 | 45,000 | 51,000 | 19,000 | 28,800 | 28,000 | 19,000 | 142,500 | 144,000 | 67,000 | 144,000 | 436 | 106 | 24 | 598 |

|

This table represents placements and salaries reported as full-time. Some individuals or schools omitted information, rendering information unusable. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

*Some schools conducted their own survey and provided raw data. |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

**Includes nonbinary, unsure, and declined to answer gender. |

||||||||||||||||||||

The employment context for 2020 graduates aligns with the stark change in focus that 2019 graduates experienced. Seventy-three percent of 2020 graduates are employed in the LIS field, a slight increase over 2019’s score (69 percent). Both years represent a notable decrease from 2018, in which nine out of 10 graduates reported being employed in the field. Somewhat fewer 2020 graduates reported employment outside of the LIS field (18 percent) versus in 2019 (23 percent). Given that unemployment was higher for this year’s graduates, while LIS jobs were up a bit, non-LIS opportunities may have been scarcer this year.

About half of employed 2020 graduates are working in either a public library (33 percent) or an academic library (19 percent). The next most prevalent landing spots are private industry (17 percent), or K–12 schools (10 percent). The numbers for public libraries and K–12 schools showed small increases over 2019, while academic libraries and private industry levels held constant. Other destinations for 2020 graduates were chosen at similar levels to the prior year’s: other academic units at a college or university (4 percent), nonprofit non-library institutions (4 percent), government libraries (3 percent), other governmental agencies (3 percent), special libraries (2 percent), or archives/special collections (2 percent). Less than 1 percent reported working for library cooperatives or vendors.

Although the majority of employed graduates express satisfaction with their current placement (65 percent), this is a clear decline from 2019 (72 percent), perhaps reflecting the uncertainty and stress of altered working conditions under the pandemic. In a similar pattern as last year, graduates doing library work in non-library settings were somewhat more satisfied (71 percent) than those in an LIS institution (68 percent), although the levels for each setting were notably lower now (80 percent and 76 percent in 2019). Graduates working outside the LIS field were the least satisfied (44 percent), a similar level to last year.

| TABLE 5: AVERAGE SALARY FOR STARTING LIBRARY POSITIONS, 2011-2020 | ||||

| YEAR | # Library Schools Represented | Avg. Full Time Starting Salary | Difference in Avg. Salary | Percentage Change |

| 2011 | 41 | $44,565 | $2,009 | 4.72% |

| 2012 | 41 | $44,503 | ($62) | -0.14% |

| 2013 | 40 | $45,650 | $1,147 | 2.58% |

| 2014 | 39 | $46,987 | $1,337 | 2.93% |

| 2015 | 39 | $48,371 | $1,384 | 2.95% |

| 2016 | 40 | $51,798 | $3,427 | 7.08% |

| 2017 | 41 | $52,152 | $354 | 0.68% |

| 2018 | 41 | $55,357 | $3,205 | 6.15% |

| 2019 | 36 | $58,655 | $3,298 | 5.96% |

| 2020 | 36 | $56,453 | ($2,202) | -3.75% |

IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON 2020 GRADUATES

This year’s survey included several questions to explore some of the ways that the pandemic affected 2020 graduates’ job seeking and employment, as well as their LIS programs.

LIS students normally can choose course delivery options, but during 2020 COVID forced programs to switch suddenly to all-online instruction. Prior to the shutdown, almost two-thirds of the 2020 graduates had elected to study via fully online instruction (64 percent), while 20 percent had preferred a hybrid modality combining on-site and online courses. Only 16 percent were learning through fully on-site courses. This distribution reflected a substantial increase over the prior year in the proportions choosing all-online instruction, but also an increase in those attending only in-person courses, with the decrease occurring in hybrid learning. Post shutdown, graduates who had planned to complete their degrees via on-site learning were evenly split on whether the sudden shift to all-online courses compromised their learning in any way; 51 percent said yes, it was problematic. Of course, since the survey is for graduates, it did not capture the impact on students who had intended to graduate in 2020, but did not finish their programs because of COVID-related issues.

Some 2020 graduates felt they missed out on work experience opportunities during their programs. COVID-related library closures affected the ability of 41 percent of 2020 graduates to do internships or practicums.

COVID-19 changed the scope of the job search for some 2020 graduates; 23 percent said they applied to jobs outside of their local area without intending to relocate, because of the increase in remote work spurred by the pandemic. Applying to work from a distance was most prevalent for graduates working outside of the LIS field (33 percent) or those performing library work outside of a library (32 percent). Employed 2020 graduates in general were much less likely to have relocated for their new job than last year’s graduates were (16 percent versus 26 percent of 2019 grads). This likely reflects the lack of mobility created by the shutdown.

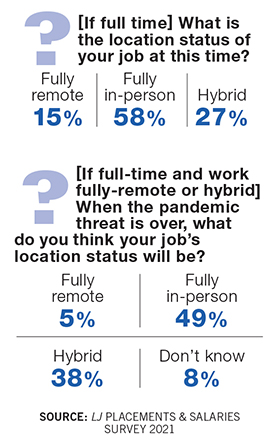

Employed graduates were asked about the modality of their job. More than half (58 percent) reported that they were working fully in person, while 27 percent were working in a hybrid circumstance with some in-person and some remote work. Only 15 percent were working completely remotely. However, exclusively remote work was more common for graduates employed outside of the LIS field (35 percent) than inside it (15 percent). Work setting is often a determinant of modality. Remote work was especially common for graduates working full-time in private industry settings (54 percent) or in special libraries (42 percent). Hybrid work arrangements were more common in no-profit organizations (52 percent) and archives/special collections (50 percent). Three-fourths of these new graduates working in public and school libraries said they were working fully in-person.

Graduates working full-time using either fully remote or hybrid modalities were asked to speculate about how they might do their job after the pandemic ends; about half expect to return to working fully in-person (49 percent), while 38 percent anticipate using a hybrid model. About half of those working outside the LIS field expect to return to a hybrid model, with 32 percent expecting to be fully in-person.

CAREER TRAJECTORY

The class of 2020 is equally split between new professionals and those launching a second career; however, library work experience is an important factor in their job search outcomes. Twenty-one percent had no experience working in a library either before or during their LIS programs, while 39 percent had both prior and concurrent library experience. Forty-five percent of the unemployed graduates lacked any library work experience, while 46 percent of those now hired to work in an LIS field had worked in a library both before and during their studies. Graduates now working outside of the LIS field were not affected in the same way, as 52 percent of them had no library work experience.

Two-thirds of employed 2020 graduates remained with an employer or position they held prior to joining or while attending their master’s program. This was true regardless of whether the graduate was working within or outside of the LIS field. This was a meaningful increase from the 2019 results (59 percent), and possibly reflects uncertainty and diminished options during the pandemic. Staying with their current employer and achieving their masters’ degree brought rewards for many 2020 graduates in the form of raises (28 percent), promotions (19 percent), or progression to professional staff (17 percent). About half saw no change to their circumstances after gaining the master’s, although it is possible that the COVID-19 environment might cause delays in delivering these rewards.

In addition to employment, LIS graduates also have the option of pursuing another advanced degree. About 30 percent of 2020 graduates said they would definitely or probably seek another advanced degree. About half said they would “probably not” earn a second graduate degree, while 21 percent ruled it out completely. About a fourth of 2020 graduates already had another advanced degree when they started their LIS programs, and 5 percent were dual enrolled in a second program while completing their LIS degree.

| TABLE 6: FULL-TIME SALARIES OF REPORTING PROFESSIONALS BY PRIMARY JOB ASSIGNMENT | ||||||

| Primary Job Assignment | No. Rec'd | % of Total | Low Salary | High Salary | Average Salary | Median Salary |

| Access Services | 8 | 1.8% | $26,000 | $47,000 | $41,589 | $44,000 |

| Administration | 43 | 9.7% | 25,000 | 125,000 | 56,718 | 52,000 |

| Adult services | 23 | 5.2% | 30,000 | 59,405 | 45,498 | 45,000 |

| Archival and preservation | 16 | 3.6% | 35,000 | 65,000 | 50,404 | 50,022 |

| Budgeting/finance | 2 | 0.5% | 32,000 | 55,000 | 43,500 | 43,500 |

| Children's services | 43 | 9.7% | 23,815 | 64,434 | 43,611 | 43,000 |

| Circulation | 14 | 3.2% | 20,000 | 84,000 | 42,737 | 41,000 |

| Collection development/Acquisitions | 15 | 3.4% | 21,000 | 75,010 | 45,721 | 45,240 |

| Communications, PR, and social media | 5 | 1.1% | 31,600 | 60,944 | 43,778 | 41,344 |

| Data analytics | 3 | 0.7% | 40,000 | 84,000 | 56,000 | 44,000 |

| Data curation & management | 5 | 1.1% | 39,000 | 72,000 | 54,200 | 52,000 |

| Digital content management | 7 | 1.6% | 28,000 | 65,000 | 43,589 | 42,000 |

| Government documents | 5 | 1.1% | 38,000 | 90,000 | 53,600 | 45,000 |

| Information technology | 2 | 0.5% | 28,000 | 54,000 | 41,000 | 41,000 |

| Knowledge management | 5 | 1.1% | 41,700 | 95,000 | 59,740 | 50,000 |

| Market intelligence/Business research | 3 | 0.7% | 60,000 | 73,000 | 67,667 | 70,000 |

| Metadata, Cataloging & Taxonomy | 15 | 3.4% | 25,000 | 80,000 | 52,055 | 50,000 |

| Outreach | 8 | 1.8% | 31,000 | 63,151 | 47,062 | 48,671 |

| Patron programming | 3 | 0.7% | 45,000 | 50,000 | 47,000 | 46,000 |

| Public services | 20 | 4.5% | 32,000 | 70,710 | 46,828 | 48,167 |

| Records management | 8 | 1.8% | 39,350 | 62,000 | 45,294 | 43,500 |

| Reference/Information Services | 36 | 8.1% | 25,000 | 84,000 | 51,310 | 50,100 |

| School librarian/School Library Media Specialist | 50 | 11.3% | 38,000 | 91,772 | 53,578 | 50,500 |

| Solo librarian | 6 | 1.4% | 38,091 | 95,000 | 51,515 | 44,500 |

| Systems Technology | 6 | 1.4% | 45,000 | 68,000 | 56,000 | 55,000 |

| Teacher librarian | 19 | 4.3% | 37,000 | 84,000 | 60,871 | 59,790 |

| Technical services | 13 | 2.9% | 28,000 | 66,000 | 45,077 | 45,000 |

| Training, Teaching & Instruction | 20 | 4.5% | 28,800 | 70,500 | 50,915 | 49,000 |

| User experience/Usability analysis | 3 | 0.7% | 55,000 | 93,000 | 71,000 | 65,000 |

| YA/Teen services | 12 | 2.7% | 27,000 | 71,000 | 51,008 | 54,629 |

| Other | 25 | 5.6% | 19,000 | 144,000 | 58,563 | 54,000 |

| This table represents full-time placements reported by primary job assignment. | ||||||

SALARIES DIP, BUT COULD BE WORSE

As mentioned above, the 2020 average salary of $56,453 was down about 4 percent from last year’s high of $58,655, but still exceeded all of the prior 10 years’ averages. The median is $51,000, also down about 4 percent from the 2019 median of $53,000. Only 137 employed graduates said they receive an hourly wage, and most of them work in an LIS context. The 2020 average hourly rate of $19.53 is 34 cents lower than last year’s average, yielding an annual full-time salary of $40,622, a decline of about 2 percent from last year.

The current average full-time salary of women graduates ($55,461) remains below that for men ($63,393). However, this year’s gender differential (12.5 percent) was cut considerably, compared to 2019’s gaping difference of 20 percent. Sadly, this year’s move towards salary equity is more the result of a large drop (almost 10 percent) in the average for men, not an increase in the average for women. This improvement does put the overall differential back in the neighborhood of the 2018 (10 percent) and 2017 (12 percent) levels, and is smaller than the 2016 (18 percent) gap. There is also a regional bright spot, as the 2020 average salaries for women were higher than for men in both the Mountain and International regions.

Average salary levels vary substantially by the type of organization. This year’s graduates working in private industry enjoy the highest average salary of $83,007. Nonprofit organizations are the next most lucrative, at $55,658. School librarians have the highest average salary for a library setting ($54,438), followed by special librarians ($51,843), academic librarians ($51,425), government librarians ($50,943), and public librarians ($46,866). Graduates working in archives or special collections are earning the lowest average salary ($46,311).

WHERE THEY WORK, WHAT THEY DO

Continuing a theme that began last year, even fewer 2020 graduates described themselves as a librarian working for a library (56 percent, and 59 percent for 2019, versus over two-thirds of the graduates of the prior two years). Only 5 percent called themselves a librarian who wasn’t working in a library. Current graduates called themselves “non-librarians” working in a library (20 percent) or outside of one (19 percent ) at a similar rate to last year’s.

Given the opportunity to select their primary professional duty from a list, 2020 graduates gave some different responses than we saw in 2019. Children’s services and perennial leader reference and information services (both 9 percent) topped the list. School librarianship (8 percent), administration (7 percent), adult services (6 percent), and circulation (6 percent) completed the top six positions. This may be the result of changes in job offerings because of COVID-19.

The most notable change was the precipitous drop of user experience/usability analysis (less than 1 percent), which fell to 26th place, from 2nd place (7 percent) in 2019. UX/UA duties were far less prevalent this year even for graduates working outside LIS (only 4 percent now versus 37 percent in 2019). This might indicate a change in UX job opportunities or may reflect that UX research was suspended for safety reasons during COVID-19. Results from the 2021 graduates will likely help provide clarity. Graduates working outside of LIS were primarily involved in administration (15 percent), data analytics (11 percent), or IT (7 percent).

When graduates were asked to identify all the duties involved in their jobs, the 2020 list was quite similar to last year’s. Reference/information services (47 percent) was the most frequently chosen, followed by collection development/acquisition (37 percent), circulation (34 percent), patron programming (33 percent), and outreach (32 percent). New graduates employed outside the LIS field were most often engaged in administration (28 percent), followed by training/teaching/instruction (18 percent), IT (17 percent), and data analytics (13 percent). Nine percent of graduates perceived their job as in an emerging area of LIS practice, which is lower than the two prior years (10 percent and 16 percent respectively).

| TABLE 7: COMPARISON OF FULL-TIME SALARIES BY TYPE OF ORGANIZATION AND PLACEMENT REGION | |||||

| TOTAL PLACEMENTS | LOW SALARY | HIGH SALARY | AVERAGE SALARY | MEDIAN SALARY | |

| PUBLIC LIBRARIES | |||||

| Northeast | 34 | $27,000 | $125,000 | $50,866 | $49,570 |

| Southeast | 35 | 27,000 | 144,000 | 47,557 | 45,000 |

| South Central | 25 | 23,815 | 59,405 | 40,887 | 41,344 |

| Midwest | 41 | 19,999 | 90,000 | 45,146 | 43,000 |

| Mountain | 17 | 36,000 | 60,000 | 48,049 | 50,000 |

| Pacific | 12 | 35,000 | 71,000 | 50,176 | 48,906 |

| International | - | - | - | - | - |

| Remote | - | - | - | - | - |

| ALL PUBLIC | 164 | 19,999 | 144,000 | 46,866 | 45,000 |

| COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY | |||||

| Northeast | 27 | 34,000 | 75,000 | 54,867 | 50,000 |

| Southeast | 29 | 29,000 | 85,000 | 49,157 | 49,333 |

| South Central | 24 | 19,000 | 60,500 | 43,185 | 44,750 |

| Midwest | 36 | 36,000 | 100,279 | 53,186 | 52,500 |

| Mountain | 8 | 30,000 | 75,000 | 46,213 | 44,350 |

| Pacific | 19 | 35,000 | 108,000 | 59,756 | 55,000 |

| International | - | - | - | - | - |

| Remote | 1 | 42,000 | 42,000 | 42,000 | 42,000 |

| ALL ACADEMIC | 144 | 19,000 | 108,000 | 51,425 | 49,367 |

| SCHOOL LIBRARIES | |||||

| Northeast | 12 | 38,500 | 80,000 | 57,496 | 57,500 |

| Southeast | 19 | 38,000 | 84,000 | 53,168 | 51,000 |

| South Central | 25 | 23,000 | 69,000 | 52,607 | 56,000 |

| Midwest | 12 | 45,000 | 76,000 | 57,313 | 51,000 |

| Mountain | 4 | 37,000 | 48,000 | 41,750 | 41,000 |

| Pacific | 7 | 40,000 | 91,772 | 57,767 | 50,000 |

| International | 2 | 60,000 | 75,000 | 67,500 | 67,500 |

| Remote | - | - | - | - | - |

| ALL SCHOOL | 81 | 23,000 | 91,772 | 54,438 | 53,000 |

| GOVERNMENT LIBRARIES | |||||

| Northeast | 2 | 38,000 | 56,000 | 47,000 | 47,000 |

| Southeast | 11 | 39,000 | 92,000 | 59,639 | 57,000 |

| South Central | 5 | 25,000 | 48,000 | 36,000 | 33,000 |

| Midwest | 3 | 28,800 | 55,356 | 43,885 | 47,500 |

| Mountain | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pacific | 1 | 55,000 | 55,000 | 55,000 | 55,000 |

| International | 1 | 55,000 | 55,000 | 55,000 | 55,000 |

| Remote | - | - | - | - | - |

| ALL GOVERNMENT | 23 | 25,000 | 92,000 | 50,943 | 49,500 |

| PRIVATE INDUSTRY | |||||

| Northeast | 18 | 40,000 | 132,500 | 86,080 | 87,750 |

| Southeast | 9 | 35,766 | 112,500 | 71,918 | 75,000 |

| South Central | 8 | 38,000 | 117,500 | 79,063 | 77,500 |

| Midwest | 38 | 30,000 | 137,500 | 80,750 | 82,500 |

| Mountain | 1 | 107,500 | 107,500 | 107,500 | 107,500 |

| Pacific | 31 | 35,000 | 142,500 | 89,806 | 95,000 |

| International | 2 | 40,000 | 52,500 | 46,250 | 46,250 |

| Remote | - | - | - | - | - |

| ALL PRIVATE INDUSTRY | 107 | 30,000 | 142,500 | 83,007 | 82,500 |

| SPECIAL LIBRARIES | |||||

| Northeast | 4 | 26,000 | 73,000 | 53,500 | 57,500 |

| Southeast | 3 | 28,000 | 75,500 | 54,333 | 59,500 |

| South Central | 2 | 40,000 | 60,000 | 50,000 | 50,000 |

| Midwest | 4 | 25,000 | 66,000 | 50,250 | 55,000 |

| Mountain | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pacific | 1 | 67,000 | 67,000 | 67,000 | 67,000 |

| International | 1 | 32,642 | 32,642 | 32,642 | 32,642 |

| Remote | - | - | - | - | - |

| ALL SPECIAL | 15 | 25,000 | 75,500 | 51,843 | 55,000 |

| ARCHIVES/SPECIAL COLLECTIONS | |||||

| Northeast | - | - | - | - | - |

| Southeast | 3 | 40,000 | 63,000 | 52,333 | 54,000 |

| South Central | 2 | 40,000 | 49,998 | 44,999 | 44,999 |

| Midwest | 3 | 43,014 | 47,100 | 45,038 | 45,000 |

| Mountain | 2 | 40,000 | 41,000 | 40,500 | 40,500 |

| Pacific | - | - | - | - | - |

| International | - | - | - | - | - |

| Remote | - | - | - | - | - |

| ALL ARCHIVES/SPECIAL COLLECTIONS | 10 | 40,000 | 63,000 | 46,311 | 44,007 |

| NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS | |||||

| Northeast | 2 | 45,000 | 119,000 | 82,000 | 82,000 |

| Southeast | 5 | 43,000 | 65,000 | 55,200 | 55,000 |

| South Central | 2 | 39,000 | 43,000 | 41,000 | 41,000 |

| Midwest | 7 | 37,000 | 65,000 | 49,071 | 47,000 |

| Mountain | - | - | - | - | - |

| Pacific | 2 | 55,000 | 75,000 | 65,000 | 65,000 |

| International | - | - | - | - | - |

| Remote | 1 | 62,000 | 62,000 | 62,000 | 62,000 |

| ALL NONPROFIT | 19 | 37,000 | 119,000 | 55,658 | 52,500 |

| OTHER ORGANIZATIONS | |||||

| Northeast | 5 | 35,000 | 65,000 | 46,000 | 45,000 |

| Southeast | 7 | 33,000 | 98,000 | 57,625 | 52,000 |

| South Central | 2 | 20,893 | 53,826 | 37,360 | 37,360 |

| Midwest | 7 | 35,000 | 84,000 | 55,771 | 50,000 |

| Mountain | 2 | 41,000 | 42,000 | 41,500 | 41,500 |

| Pacific | 5 | 50,000 | 100,000 | 67,800 | 67,000 |

| International | - | - | - | - | - |

| Remote | 1 | 60,000 | 60,000 | 60,000 | 60,000 |

| ALL OTHER | 29 | 20,893 | 100,000 | 54,500 | 50,045 |

|

This table represents only full-time salaries and all placements reported by type. Some individuals omitted placement information, rendering some information unusable. |

|||||

PREPARING FOR PROFESSIONAL LIVES

Graduates identified the experiences or activities that proved to be the most helpful for securing their first professional positions. While 70 percent cited previous employment experience, several also credited elements of their master’s programs. Technology skills (e.g., database searching, HTML coding, or other Internet-based skills) were mentioned by 42 percent, followed by internships/fieldwork/practicums (39 percent). Subject specialization training (such as in cataloging or reference) was important for 33 percent of graduates, similar to networking with professionals in their field of interest (32 percent). These four elements were also identified most frequently last year, although response levels for all were lower this year.

The majority of 2020 graduates completed at least one practicum (55 percent) as an LIS student, and 19 percent did two or more. Most of these practicums were solely in person (56 percent), although 33 percent were a combination of in-person and remote work. Some of these may have been switched to remote mode when the shutdown occurred.

Graduates were asked about how much student loan debt they are carrying from their LIS degree program. Thirty-nine percent indicated they are debt-free, leaving 61 percent with some level of financial obligation. Twenty-one percent owe between $25,000 to $49,999, while 17 percent owe between $10,000 and $24,999. Fourteen percent owe $50,000 or more. For those carrying student loans, the average level of debt is $37,900. The highest average debt level is carried by graduates working outside of the LIS field ($45,400), the currently unemployed ($43,800), and those working part-time ($41,800).

TALES OF THE QUEST

Graduates who did not remain with a previous employer or position shared about their approach to and experiences with the job search. On average, 2020 graduates began their job search 5.3 months before graduation. Almost half (49 percent) began their job searches between one to six months before graduation, with 26 percent initiated between four to six months. Very few waited more than a month after graduating to begin (6 percent). This pattern is similar to 2019, except that a few more current graduates began their searches very early, while somewhat fewer waited until after graduation to start looking.

Fewer 2020 job seekers had nailed down their new position before graduation (35 percent versus 46 percent in 2019), possibly reflecting the unusual and uncertain job market under COVID-19. Graduates doing library work outside of a library were most likely to have their job in hand before graduation (42 percent), although those working outside the LIS field were the least likely (21 percent). Graduates who had to seek employment after finishing their LIS programs had to wait an average of 5.4 months before placement, more than a month longer than the 2019 average (4.2 months). Thirty-eight percent of these job seekers took six months or more to be hired, which is also up from 2019.

Each graduate provided up to three resources they found most helpful for their job search. More than 36 different sources were named, 12 of which were mentioned by at least 6 percent of the 2020 job hunters. Resource categories included general employment sites (Indeed, Linked In), trusted partners (ALA job list), government sites at different levels, university job sites and listservs, and specific employer/institution websites, among others.

The top five resources were Indeed.com (34 percent), the ALA JobList (26 percent), city/state/regional websites (26 percent), LinkedIn (18 percent), and specific institution/employer websites (14 percent). All five of these resources were mentioned more frequently than they were last year. Campus job boards/online discussion lists were also mentioned, but by fewer graduates than last year (12 percent versus 19 percent in 2019). This may reflect the switch to all-online courses, making physical job boards inaccessible. The next six resources were Archives Gig (9 percent), professional association job boards (9 percent), Google Jobs (7 percent), GovernmentJobs (6 percent), HigherEd Jobs (6 percent), and networking/networking events (6 percent). Google Jobs is a newcomer to the upper sections of the list, but the other five sources in this second tier were mentioned by somewhat fewer graduates than last year.

This rank order held true for graduates employed in a library science institution. However, Indeed and LinkedIn were the most important sources for graduates employed outside the LIS field and those doing library work outside of a library.

| TABLE 8: FULL-TIME SALARIES BY TYPE OF ORGANIZATION AND GENDER | ||||||||||||||||||

| TOTAL PLACEMENTS | LOW SALARY | HIGH SALARY | AVERAGE SALARY | MEDIAN SALARY | ||||||||||||||

| Women | Men | Nonbinary* | All | Women | Men | Nonbinary* | Women | Men | Nonbinary* | Women | Men | Nonbinary* | All | Women | Men | Nonbinary* | All | |

| PUBLIC LIBRARY | 119 | 27 | 10 | 166 | $20,000 | $33,000 | $37,000 | $90,000 | $144,000 | $63,151 | $45,885 | $53,657 | $46,347 | $46,883 | $45,000 | $50,000 | $46,325 | $45,023 |

| COLLEGE/UNIVERSITY | 105 | 28 | 2 | 147 | 19,000 | 30,500 | 29,000 | 108,000 | 95,000 | 32,000 | 49,813 | 55,778 | 30,500 | 51,586 | 48,000 | 50,350 | 30,500 | 49,400 |

| SCHOOL LIBRARY | 72 | 5 | 3 | 81 | 23,000 | 40,000 | 50,000 | 91,772 | 56,000 | 51,000 | 55,020 | 50,400 | 50,333 | 54,438 | 54,000 | 54,000 | 50,000 | 53,000 |

| GOVERNMENT LIBRARY | 12 | 8 | 2 | 23 | 25,000 | 28,800 | 38,000 | 92,000 | 90,000 | 42,000 | 50,908 | 53,225 | 40,000 | 50,943 | 51,500 | 52,250 | 40,000 | 49,500 |

| PRIVATE INDUSTRY | 70 | 29 | 3 | 109 | 33,000 | 30,000 | 35,000 | 142,500 | 137,500 | 57,500 | 82,646 | 90,138 | 45,500 | 82,383 | 82,500 | 87,500 | 44,000 | 82,500 |

| SPECIAL LIBRARY | 13 | - | 2 | 15 | 25,000 | - | 28,000 | 75,500 | - | 67,000 | 52,511 | - | 47,500 | 51,843 | 55,000 | - | 47,500 | 55,000 |

| ARCHIVES/SPECIAL COLLECTIONS | 8 | 2 | - | 10 | 40,000 | 40,000 | - | 63,000 | 45,000 | - | 47,264 | 42,500 | - | 46,311 | 45,057 | 42,500 | - | 44,007 |

| NONPROFIT ORGANIZATION | 15 | 4 | - | 20 | 37,000 | 40,000 | - | 119,000 | 62,000 | - | 54,833 | 49,500 | - | 54,775 | 52,500 | 48,000 | - | 51,750 |

| OTHER ORGANIZATION | 24 | 4 | 2 | 30 | 20,893 | 35,000 | 45,000 | 100,000 | 67,332 | 67,000 | 55,424 | 48,333 | 56,000 | 54,517 | 52,000 | 45,500 | 56,000 | 51,023 |

| This table represents only full-time salaries and all placements reported by type. Some individuals omitted placement information, rendering some information unusable. | ||||||||||||||||||

| *Includes nonbinary, other, and declined to answer gender. | ||||||||||||||||||

SCHOOL PLACEMENT HELP

Twenty percent of the responding LIS schools say they offer some kind of formal mentoring program focused on the professional development of students, down from 25 percent in 2019.

On average, each school made students aware of 384 job opportunities in 2020, which is about 4 percent fewer than the prior year. This decrease could reflect that not as many jobs were offered, or that schools had fewer ways to provide their students with this information because of the switch to all-online for COVID, or both. Listserv announcements were the most common tool LIS schools used to inform their students about job offerings (94 percent), up slightly from last year. Social media use for this purpose was also higher this year (56 percent). Both were usable during the shutdown. In contrast, two other strategies were used substantially less in 2020: posting announcements on bulletin boards or in student areas (33 percent, down from 44 percent in 2019) and through student groups or other student activities (44 percent, down from 47 percent). Only 22 percent of the schools host a formal placement services center. Almost all schools reported that the presence of online employment platforms like Indeed have not affected their use of resources to share job announcements with students, while the remaining 11 percent indicated they are now using more resources to share job announcements.

Some general impressions held by schools about aspects of this year’s salaries and placements do not align with the graduates’ reports of their experience. Based on position announcements, almost half of the schools (47 percent) indicated that 2020 starting salaries were about the same as 2019, but actual starting salaries for employed graduates were down. Forty-two percent of schools did perceive that 2020 graduates required more time for placement than 2019 ones did, but 58 percent thought the placement time was about the same.

In last year’s survey, half of the LIS schools anticipated that the pandemic would affect how they would need to support their 2020 graduates’ placement efforts, requiring more time and effort and changes in processes, to compensate for hiring freezes in the pandemic. However, in the current survey, the majority of schools (61 percent) stated that COVID did not affect how they supported their 2020 graduates in their job search efforts, while 39 percent felt that the pandemic did affect their support. For schools that did not make changes, this may reflect the fact that much of their hiring support was already delivered through online means, and therefore translated seamlessly to the all-online shutdown environment.

Unsurprisingly, this hard year left its mark on the job search for new librarians as on all else. But both schools’ tools and the job market proved more adaptive and resilient than might have been feared.

HOW THE SURVEY WORKS

Each year, the LJ placement and salaries survey serves the LIS community by providing a longitudinal lens into the experiences and attitudes of job-seeking graduates, and the support of their academic institutions. LJ invited 53 of the American Library Association-accredited library and information science schools located in the United States to participate in the annual placement and salary survey. Thirty-six schools responded by providing information about their 2020 graduates. Twenty-nine of these schools participated by sending a link for the LJ online survey to all their 2020 graduates. The other seven participating schools performed their own independent assessment of their graduates, and then shared these results with LJ: San José State, University of Michigan, University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, Kent State, Indiana-Bloomington, Washington, and Catholic University. The independent assessments conducted by these seven schools did not necessarily include all of the questions used in the LJ survey.

The data analyzed for this article are the aggregation of responses from 28 percent of the 4,516 total graduates reported by this year’s 36 participant schools. This year’s respondent base was almost 6 percent larger than last year’s, and yielded a 2 percent higher overall response rate.

There was a wide range of response rates among individual schools. Schools that sent their own surveys were rewarded with responses from as many as 85 percent of their graduates, or as few as 10 percent. Among the schools that forwarded the LJ survey to their graduates, response rates varied from a high of 58 percent to a low of 10 percent. LJ requires that a 10 percent threshold be met.

This year, 16 schools elected not to participate in the survey or failed to respond to calls for participation: SUNY-Albany, Chicago State, University of Denver, Dominican University, Drexel University, University of California–Los Angeles, Florida State University, University of Iowa, Louisiana State University, North Carolina Central University, Queens College, University of Pittsburgh, University of Rhode Island, University of South Carolina, University of South Florida, and University of Texas–Austin. Data provided by the University of Missouri was not included in the study because its survey response rate fell short of the required 10 percent threshold. Southern Connecticut State University is newly accredited, and will be asked to participate next year.

Canadian LIS programs conduct their own assessments and do not participate in the LJ annual survey. This includes programs at Alberta, British Columbia, Dalhousie, McGill, Montreal, Ottawa, Toronto, and Western Ontario. The University of Puerto Rico also does not participate.

LIMITATIONS

The purpose of this report is to provide the LIS professions with a snapshot of the graduates’ experiences entering the job market, and to identify potential trends in comparison to prior years of the study. It is not a comprehensive examination of all employment outcomes. The applicability of the survey findings is limited because graduates’ participation in the study is self-selected rather than constituting a representative sample, and the survey questions on the independent surveys administered by some schools may vary somewhat. Data from some LIS schools may be incomplete, and other schools chose not to participate. Not all LJ administered surveys were complete because graduates were allowed to skip any question on the survey or leave the survey without completing it.

Suzie Allard (sallard@utk.edu) is Professor of Information Sciences and Associate Dean of Research, University of Tennessee College ofCommunication & Information, Knoxville, and winner of the 2013 LJ Teaching Award.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy: