University of Iowa Librarians Use Medical Imaging Technology To Reveal Hidden Book Fragments

Often, medieval book bindings—as many as one in five from the 15th and 16th centuries—are reinforced with fragments of pages from older printed volumes that bookbinders considered obsolete. Without the option of dismantling precious books to reveal the fragments, specialists turn to x-ray technology to reveal words that have been hidden from view for hundreds of years. A team at the University of Iowa recently used familiar medical technology—a computerized tomography (CT) scanner—to do just that.

|

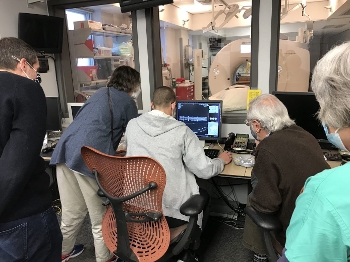

Preparing to scan three volumes of Historia animaliumPhoto credit: Giselle Simón |

Rare book collections are full of hidden treasures, and skilled librarians and scholars are experts in uncovering their secrets. As technology improves, so do their options for examining the oldest manuscripts. Often, medieval book bindings—as many as one in five from the 15th and 16th centuries—are reinforced with fragments of pages from older printed volumes that bookbinders considered obsolete. Without the option of dismantling precious books to reveal the fragments, specialists turn to x-ray technology to reveal words that have been hidden from view for hundreds of years. A team at the University of Iowa recently used familiar medical technology—a computerized tomography (CT) scanner—to do just that.

Prior wisdom in the field said that CT scanning does not work effectively for revealing materials like medieval fragments. Instead, the main type of scanning that has been used for books—an x-ray fluorescence (XRF) scanner—has been used effectively on books as well as cultural heritage objects like paintings. While providing very clear images, this method of scanning is expensive and time-consuming, requiring six to eight hours, if not more, to scan a single object. CT scanning, by contrast, is relatively quick and can scan numerous items at once.

According to Eric Ensley, curator of rare books and maps at the University of Iowa, recent developments in CT scanning technology meant the time was right to revisit the possibilities of this tool. “We were not trying to overturn [XRF] as a great method for revealing fragments,” said Ensley, “but if you can take an entire library and go over to the local medical center, and pop into the CT scanner 20 to 30 books at a time—it may give you an idea of what might be worth investigating more fully” with a greater investment of time or funds.

“It’s a way to potentially scan a lot of published books to look for manuscripts in a single library collection, relatively inexpensively if you are part of a research university” said Katherine Tachau, professor emerita of history at the University of Iowa. “I say relatively because specialist time on a clinical sized CT scanner is not cheap, from the standpoint of libraries or people in humanities. But you can do a lot quickly…and you don’t have to buy new technology.”

EXPERIMENTS IN IMAGING

This research at the University of Iowa began in earnest with a 2020 interdisciplinary conference called “More Than Meets the Eye,” which offered an opportunity to exchange research and expertise, and explore ideas, on the use of enhanced digital imaging technologies to study previously inaccessible cultural artifacts. This led to the idea for an institute at Iowa combining medical imaging technology with the expertise of librarians; members of the Stanley Museum of Art and Iowa Institute for Biomedical Imaging; and faculty in the art history, classics, engineering, medicine, and history departments. In April, this team published an article on their research, “Using computed tomography to recover hidden medieval fragments beneath early modern leather bindings, first results,” in the journal Heritage Science.

|

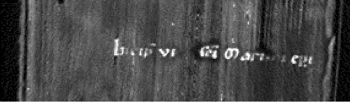

Examining a scan of the book's spinePhoto credit: Giselle Simón |

The project started small—scanning three volumes of Historia animalium, an early encyclopedia of zoology. These offered “a perfect test case,” said Ensley, as damage to the spine of one of the books had already revealed hidden fragments that could be compared to anything revealed within the other two intact bindings. Working with Eric Hoffman of the university’s Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver College of Medicine, the team piled all three books onto the CT scanner at once, and the scans revealed legible text from a Latin Bible. The fragments are hundreds of years older than the 16th-century book whose binding they were used to reinforce. While the scanning is “not exactly instantaneous,” said Tachau, “there was a moment when we could see that we were penetrating the spine and that we were seeing things there, and then we saw a couple of recognizable letters. That was when we knew it would work.”

Images from a CT scanner—designed to take x-ray images of human bodies in “slices”—are not always perfectly legible, and do require some processing. “The good news for us is the way that the spines of books are structured—they can mimic some forms in the human body,” said Ensley. Specifically, imaging experts from the University of Iowa College of Engineering noticed that book spines are curved like an eyeball. They were able to “hack” existing software used to create flattened images of eyes, and effectively “make legible quite a bit more of the fragments,” said Ensley. “The scanning takes very little time, but getting the data and reconstructing images from it, and then using software to make those images reveal what they have, takes hours and hours and hours. It is by far the most laborious part of it,” said Tachau, who also noted that the “second most laborious part of it is the work of the conservator to prepare books to be moved from one environment on campus across to another and to be stabilized in the machine.”

|

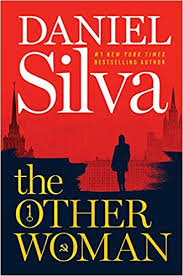

Scanned text fragmentImage courtesy of the University of Iowa Scientific Imaging and Conservation of Cultural Artifacts team |

“I didn’t have particularly high hopes [for] the CT scanning, hoping maybe we’d get a couple of things,” said Ensley, who told LJ he was pleasantly surprised by the legible images of fragments that have been revealed thus far. The team has recently started work with a new CT scanner—a photon-counting scanner boasting new technology and improved imaging capabilities—and anticipate better resolutions from those scans. This new scanner is known for “increased clarity of the images. It’s been a boon for medicine, and we are hoping it will help us even more in our research,” said Ensley. Researchers hope to make further strides on scanning different colors of inks; some colors show up more on scans than others, because of the composition of the ink. For example, “we haven’t had a good example of green ink in a CT scanner—made from copper oxide,” said Ensley. The next phase of this research will aim to see what is possible.

The University of Iowa team received grants from the university to facilitate the research, supporting a multidisciplinary team of professors from the humanities, radiology, veterinary sciences, and engineering in addition to the librarians. “We are very fortunate to have this research setup here [at Iowa]—you have the availability of the major medical hospital and experts in the field,” said Ensley. “If you are a campus that has a medical institution attached to it, this is a feasible process for you to test out. Scanning itself is one of the least expensive parts of what we did—it was the time buyouts for people to do the research to figure out if this would work in the first place,” he told LJ.

A longer-term goal of Ensley’s is for major research universities to share resources to digitize materials from smaller institutions without ready access to a medical center like that at Iowa, he said. This would open the door to making a wider array of rare books and objects visible and available in the vein of the Peripheral Manuscripts Project at Indiana University Bloomington. “We are just now starting to see an interest in revealing hidden collections in libraries,” said Ensley, and “are keen on promoting medieval fragments as hidden collections, literally.”

Tachau expressed enthusiasm for the possibilities of this work on digital imaging for scholarship on books and on history. This work could contribute to “projects to piece together, by digital means, fragments that have shown up in lots of different collections,” she said, so “you might be able to reconstruct books, matching what fragments go together.” In addition, she told LJ, “Finding scraps in book bindings tell us when and where binders were doing this,” expanding understanding of where and how people worked, traveled, and lived. This is, Tachau said, “one reason physical, material books are worth preserving—physical books tell us things that the digital books do not.” This work on fragments is introducing interesting conversations about how libraries can present these items, and offering an opportunity to expand our understanding of the history of bookmaking and how librarians can showcase a more holistic view of the book.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!