Business as Unusual: LJ's 2022 Public Library Fundraising Survey

The results from LJ’s Fall 2021 Public Library Fundraising Survey demonstrate how the COVID-19 pandemic changed the ways libraries conducted their fundraising. Like so much else in the library field, the pandemic forced library staff, administrators, and Friends groups to reconsider the best ways both to raise funds and utilize them.

LJ survey shows how public libraries met the pandemic’s challenges to fundraising

The results from LJ’s Fall 2021 Public Library Fundraising Survey demonstrate how the COVID-19 pandemic changed the ways libraries conducted their fundraising. Like so much else in the library field, the pandemic forced library staff, administrators, and Friends groups to reconsider the best ways both to raise funds and utilize them.

The results from LJ’s Fall 2021 Public Library Fundraising Survey demonstrate how the COVID-19 pandemic changed the ways libraries conducted their fundraising. Like so much else in the library field, the pandemic forced library staff, administrators, and Friends groups to reconsider the best ways both to raise funds and utilize them.

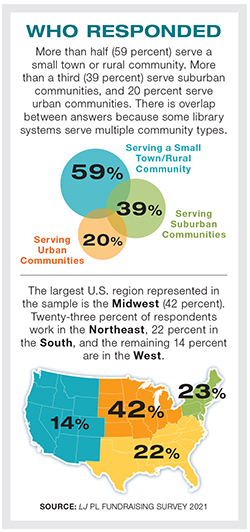

Of the nearly 300 library workers who responded last October, a slight majority (53 percent) came from libraries serving populations fewer than 25,000. The other responses were approximately evenly split among libraries serving 25,000–99,000 (22 percent) and those serving at least 100,000 (25 percent). On average, participating libraries served 135,800 people.

A considerable majority (93.5 percent) of responding libraries are fundraising during the pandemic. Of those that weren’t doing so at the time of the survey, 37.5 percent had not done so before the pandemic, and the same number do not plan to do so after the pandemic ends. Of those libraries not fundraising, 18.8 percent intend to do so in the future, and 43.8 percent may or may not.

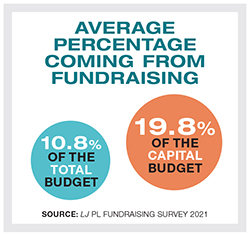

For many libraries, fundraising remains vital to their operation. Respondents estimate that, on average, nearly 11 percent of total budgets and 20 percent of capital budgets come from fundraising. When asked how the total budget percentage has changed compared with three years ago, 56 percent say it has stayed the same, with the remainder evenly split (22 percent increased, 22 percent decreased). Even more libraries report that the percentage of capital budgets coming from fundraising has not changed (66 percent), with 18 percent reporting an increase over the last three years, and 16 percent reporting a decrease.

COVID COSTS

COVID COSTS

Some libraries have found themselves more in need of funds than ever. “We have been writing grants for new materials, programs, equipment, and capital projects, and will continue to do so beyond the pandemic,” wrote Rachel Muchin Young of Frank L. Weyenberg Library in Mequon-Thiensville, WI. “Our municipalities have been naturally cautious in their spending throughout the pandemic, but library expenditures have increased as we pivot to provide essential services differently in these extraordinary times.” A survey participant in the northeast commented, “We continually combat two erroneous ideas: 1) that libraries aren’t needed anymore [and] 2) that tax dollars provide enough library funding.”

Lisa Ann Sammet of Jeudevine Memorial Library in Vermont also wrote about how pandemic-driven increases in costs have affected finances. “We are raising money for a $2.4 million addition. Costs went up a lot because of COVID. Our original estimate was $1.7 million. We are working on raising the difference. This is a big project for a small town.”

Of those who are not fundraising, some say they don’t have a need. Dallas Public Library, according to employee Chris Gifford, is largely “[f]unded by the tax[es] from residents,” with some funding for programs and summer reading provided by the Friends. Others are prohibited from doing so: Mamie Eng stated that as a municipal library, Henry Waldinger Memorial Library of Valley Stream, NY, is not permitted to fundraise.

WHERE DO THE FUNDS GO?

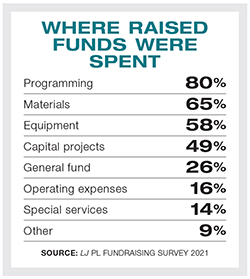

The survey determined that over the last five years, programming (80 percent) was the largest beneficiary of fundraising dollars, followed by materials (65 percent) and equipment (58 percent). Half of public libraries (49 percent) that fundraise have conducted capital campaigns.

Only 14 percent of funds have been earmarked for special services and projects such as a recording studio, maker space, lab, book drop, and story walk; vehicles; zoo passes; programming events and prizes, especially those relating to summer reading; new and expanding physical and electronic collections; a community garden; outdoor musical instruments; a new strategic plan; a library’s centennial celebration; author visits; and continuing education for the staff.

In response to the pandemic, libraries are also using raised funds for COVID relief and curbside service. Additionally, funds are financing outreach efforts aimed at patrons experiencing homelessness, at risk children, homebound patrons, and members of other vulnerable communities. Technological projects utilizing the raised funds include new computers, newspaper digitization, hotspots, phone charging stations, and an electronic message center sign.

In response to the pandemic, libraries are also using raised funds for COVID relief and curbside service. Additionally, funds are financing outreach efforts aimed at patrons experiencing homelessness, at risk children, homebound patrons, and members of other vulnerable communities. Technological projects utilizing the raised funds include new computers, newspaper digitization, hotspots, phone charging stations, and an electronic message center sign.

The survey found that “when asked whether earmarked programming and special projects were pilot or legacy services, most (56 percent) said they were a mix of both. Eleven percent said fundraised programming/special service dollars went exclusively toward new projects, and a third (33 percent) used fundraising to support existing services.”

SAME MISSION, NEW METHODS

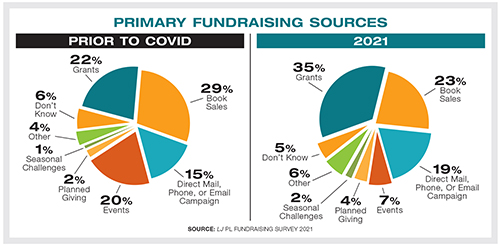

The pandemic significantly impacted fundraising methods for public libraries. The share of funds raised through grants rose by double digits, and events fell by about the same amount. The percentage naming grants as their leading fundraising source rose from 22 percent prior to the pandemic to 35 percent. The next highest fund generating methods currently employed are dallas sales (23 percent); direct mail, phone, or email campaigns (19 percent); and events (7 percent). Prior to the pandemic, the top fundraising methods were book sales (29 percent), grants (22 percent), events (20 percent), and direct mail, phone, or email campaigns (15 percent). Because of the increased emphasis on raising funds through grants, libraries have had to make changes. Nataly Anifrani of Virginia’s Chesterfield County Public Library recalled that the library “redeveloped the organizational infrastructure to support grantsmanship activities.”

An anonymous survey participant in the southern region stated that they wrote “federal grants as a part-time paraprofessional. It was an enormous amount of work. We were filling in gaps, as our counties don’t fund us at an adequate level.”

About three-quarters (74 percent) of those participating libraries that currently fundraise do so through a Friends group. During the pandemic, some libraries faced challenges owing to the complete or partial dissolution of the Friends groups that normally raise their funds.

Apart from Friends, staff in over half of libraries (57 percent), particularly medium- and small-sized libraries, do fundraising in addition to other duties.

Some 16 percent have dedicated development staff, most of whom are employed at large libraries serving populations over 100,000. Other libraries have hired employees to handle fundraising. Georgia Lomax, executive director of the Pierce County Library System, WA, wrote, “We’re lucky to have the ability to hire fundraising professionals, rather than asking a library staffer to read some books and give it a go. If you really want to include philanthropy in your funding—hire someone who knows the business! They will pay for themselves and be able to teach others how to engage and connect with people who care about your library’s mission and will want to support it with a check (or stocks, or a bequest).”

Some 16 percent have dedicated development staff, most of whom are employed at large libraries serving populations over 100,000. Other libraries have hired employees to handle fundraising. Georgia Lomax, executive director of the Pierce County Library System, WA, wrote, “We’re lucky to have the ability to hire fundraising professionals, rather than asking a library staffer to read some books and give it a go. If you really want to include philanthropy in your funding—hire someone who knows the business! They will pay for themselves and be able to teach others how to engage and connect with people who care about your library’s mission and will want to support it with a check (or stocks, or a bequest).”

A third of libraries have a library foundation that does fundraising, and a third have a donation request button on their website.

Nyama Reed of Whitefish Bay Public Library, WI, explained how the new challenges affect her position. “We are embarking on a $1,000,000 endowment campaign with a newly created library foundation. This is a totally new area for our library and a very different way of fundraising. I am taking classes through Indiana University’s Lilly School of Philanthropy to help me learn the fundamentals. Lots of other library directors have asked me about it [because] many have to [rely] on fundraising for operating or capital expenses, more so than in the past. [Wisconsin] implemented state law 10 years ago that limit the ability to raise taxes. Consequently, as costs increase we are all being pushed into becoming fundraisers. It would be interest[ing] to have a study on how laws in each state impact the need to became fundraisers to cover costs.”

As a safety precaution, many fundraising events moved from indoors to outdoors or online. “The Friends group set up tables outside on our covered terrace for an honor-system book sale to help make up for the closure of their honor-system bookstore inside the library while the library building was closed/limited,” wrote Gwin Grimes of Jeff Davis County Library, TX. “Some months they brought in more revenue that way than they did with the indoor book sale area.”

“A systemwide car raffle run by the foundation helped replace some of the funds lost to the cancellation of in-person events,” explained Jean Jacobson of Lower Merion Library System, PA. “The six libraries also increase[d] the use of social media and online giving during the pandemic.”

FUTURE FOCUSED

FUTURE FOCUSED

Some libraries will continue to use the new fundraising strategies that libraries have adopted to meet the pandemic in the future. Teresa Schmidt of Mercer Public Library, WI, found, “We had great feedback about our outdoor open house and online auction. We may keep that format in future years. We’ve also increased using our email newsletter to inform people about our fundraising activities and Friends of the Library events.”

Lomax wrote that her system will “continue with online approaches—it’s working well, from donor meetings, to our annual fundraising event, to email newsletters rather than printed. People are responding, it’s convenient for them.”

According to Reed, Whitefish Bay Public Library and its Friends group has changed how it sells books, going online. “Now that we are open to the public again, the small book sale room is available daily and we will hold our first large book sale event in November 2021. The last one was November 2019. eBay sales will continue because they now bring in over $30,000 per year.”

Despite the difficulties, some libraries have found fundraising during the pandemic to be successful. “In many respects, library fundraising during COVID has been easier, as the need is obvious and the work is much appreciated,” pointed out Nikki Maounis of Camden Public Library, ME.

“We weren’t sure what to expect, but have found that people have been very generous through the pandemic,” Lomax stated. “We have spent the last five years developing and maturing our fundraising skills and understanding, and building a foundation department and board of directors. Its growth and success has continued to increase despite the pandemic.”

According to Peter Leonard of Cedar Mill & Bethany Community Libraries, OR, libraries should embrace the fundraising process. “Many libraries are shy about fundraising. We see it as friend raising. When the community invests in library services through donations of dollars and/or volunteer time, you create more ownership. We think that creates a better library.”

Andrew Gerber, Young Adult and Media Librarian for North Brunswick Public Library, NJ, has previously written articles for LJ and Medical References Services Quarterly.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!