Safety Net: LJ Summit Looks at Library Safety and Security Issues

Keeping library staff and patrons safe in challenging times requires leadership, listening, and considering what safety and security mean in different communities.

Keeping library staff and patrons safe in challenging times requires leadership, listening, and considering what safety and security mean in different communities

Library safety and security efforts all have a common goal: to ensure that staff, volunteers, and patrons feel physically and emotionally safe. Working toward that objective, however, involves managing a range of concerns, viewpoints, and needs. What constitutes safety varies greatly among individuals; factors including race, age, disability, and/or being LGBTQIA+, can greatly impact personal risk. Safety may involve freedom from violence or harassment, not being surveilled or confronted by law enforcement, or a place to be oneself without reprisal. Staff in front-facing roles face further complexity. How can libraries navigate these considerations, listen to the voices of those affected, and provide a safer environment in increasingly volatile times?

|

WARM WELCOME Columbus Metropolitan Library CEO Patrick Losinski greets attendees at LJ’s inaugural Public Library Safety Summit. Photo by Jen Jones |

Library Journal’s Public Library Safety Summit, held at the Columbus Metropolitan Library (CML), OH, April 27–28, took on some of these questions. A mix of speakers and panelists, including staff, social-service workers, library-security directors, and more, discussed what has worked, difficulties they have encountered, and how others might incorporate those solutions into their own safety and security plans.

While there are no broad-brush answers, important takeaways surfaced. Strong and adaptive leadership that listens to and empowers staff is essential. Internal and community relationships are key to developing policies and procedures; identifying what feels safe—and unsafe—for staff and community members is a continuous process. Burnout and compassion fatigue are at a high among staff; it’s important to remember that the long haul of dealing with issues can often be harder than coping with an immediate crisis.

TRAUMA-INFORMED LEADERSHIP

The need to lead through a trauma-informed lens is an important consideration, and one that must be approached as an exploration of individual and community needs rather than as a trend to be slotted into existing practices.

Dr. Amy Acton, a physician and public-health researcher who served as director of the Ohio Department of Health from 2019–20, gave the summit’s keynote, aptly demonstrating how safety concerns map across disciplines and scenarios. Acton played a leading role in Ohio’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and saw firsthand the need for leaders to bring others along as they look at options. This is not just about having a multiplicity of voices, she noted, but drawing strength from acting together. “Being disconnected unmoors us,” she said. Mutual support helped mitigate the spread of COVID and can serve as a model during the disruptive times we are in now, she added. “This issue is not just yours to own alone,” she said. “Who else are you going to bring to the table?”

As Acton noted, trauma-informed leadership begins with the acknowledgment that leaders, whether library directors or security managers, don’t have all the answers—nor should they be expected to. Rather, they can invite staff to share firsthand knowledge and experiences, so that collaboration on strategies is a library-wide effort. Vulnerability from leadership is key; it helps ensure buy-in and support. Those in charge need to pay attention to how ready staff are to do the jobs being asked of them, and should provide a physical or virtual space for drop-in listening sessions. Communication needs to be simple, transparent, and frequent.

A trauma-informed approach has the potential to reach many areas of the library’s work by amplifying human-capital capacities rather than increasing budget lines. Pam Ryan, Toronto Public Library (TPL) director of service development and innovation, said that in the wake of recent large increases to the safety budget, the library board challenged leadership to find alternate ways to support safety and security. TPL engaged a facilitator, Third Party Public, to bring together stakeholders including employees, union reps, management, board members, and residents, who helped identify opportunities through a trauma-informed lens.

Collaborative brainstorming can have smaller-scale—but no less important—impacts as well. Six years ago, Dallas Public Library (DPL) Director Jo Giudice began bringing together staff from across the library to consider how to improve security. Solutions ranged from adding locks to staff area doors and removing outer bathroom doors—allowing security guards to look in unobtrusively—to rewriting the code of conduct to emphasize positive actions, such as “Respect customers and staff,” rather than enumerating a list of No’s. “Once you know people’s stories,” said Giudice, “it takes you to the next step of helping care for them.”

SECURITY STAFFING MODELS

The question of what type of security personnel to hire is a challenging subject for many libraries. Some rely on in-house security staff, while others contract with outside vendors or hire off-duty police officers, often depending on the library’s size and budget. Many directors have a genuine relationship with the local police department or the security personnel they hire. But library workers, particularly those from marginalized communities, may feel unsafe sharing a workspace with law enforcement no matter how positive security staff’s connections are to the library.

If you hire police, they need to be carefully vetted and should understand the mission and vision of the library, advised Michelle Hamiel, director of Racial Equity and Community Impact at Urban Libraries Council. They should be willing to build relationships with patrons. Whatever staffing model the library uses needs to fit not only the community at large, but individual library locations, she noted. “You don’t have cookie-cutter branches, so you can’t have a cookie-cutter solution.” Hamiel also encouraged libraries to hire security from within the community whenever possible, and make sure staff have sufficient training.

|

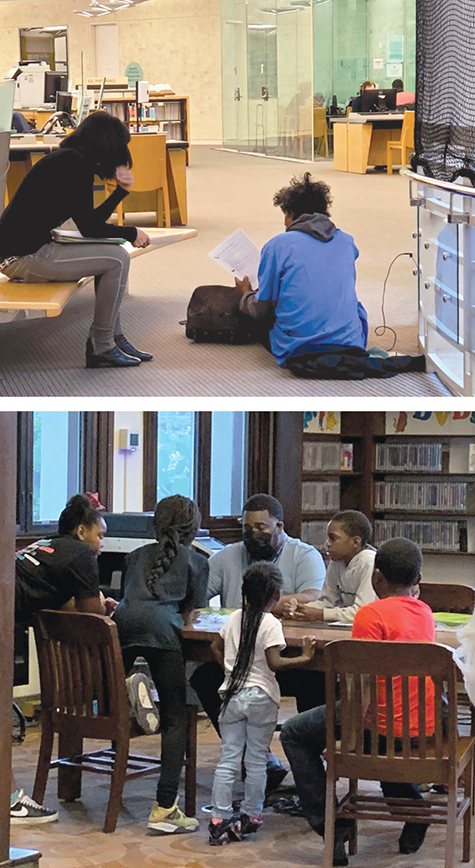

ONGOING ENGAGEMENT Top: Health and Safety Associate Ida Abolins talks to a patron found sleeping on the floor at the San Francisco Public Library, providing him with social-service resources including places to eat, shower, and rest while the shelters are closed. Bottom: at Cincinnati & Hamilton Public Library’s Avondale Branch Library, former Monitor-Mentor Marc Scribbin plays a board game with children after school. Top photo by Leah Esguerra; bottom photo courtesy of Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library |

Kaya Burgin, currently manager at the Loveland Branch of Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library, OH, grew up visiting the library’s Avondale Branch and served as the branch manager there for four years. Avondale has gone through a number of security models, and is currently seeing success with a hybrid model of hired off-duty police officers plus Monitor-Mentors—part-timers who work with kids after school. Burgin treats the officers like staff, she said, with plenty of clear communication. And while nothing is perfect, she added, “Just having police officers who look like kids in the community has been a major benefit.”

In CML’s security department, which has more than 50 full- and part-time officers across 23 locations, customer service is an important component. All officers undergo a three-week training program at the library, and security and other staff take part in regular drills covering fire, weather, and active-shooter emergencies. In 2020, because many patrons had come to distrust and fear police, officers stopped wearing uniforms and utility belts. Since then, explained Public Service Director Andrea Villanueva, the library has seen a decrease in the number of security incidents.

SOCIAL SERVICES

A growing number of libraries are embedding social workers or peer navigators as proactive safety resources to connect patrons with the services they need and build relationships. While having a social worker in place doesn’t eliminate the need for security, they often complement security roles, and can keep situations from escalating.

The pioneering social service program at San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) consists of a team of Health and Safety Associates (HASAs), library outreach workers with lived experiences of homelessness and other challenges. In addition to reaching out to patrons, the team has established relationships with community organizations and maintains a database of free community resources that library staff can also use. They take a compassionate approach, starting conversations casually to find out what services might benefit the library’s underserved or unhoused users. HASAs don’t enforce regulations, but can intervene in matters such as hygiene, inappropriate attire, or sleeping in the library, when calling security personnel isn’t appropriate, said SFPL Social Service Program Supervisor Leah Esguerra. In those cases, the patron is offered information that can help—where to find a shower, clothing, or shelter—which then opens the opportunity for them to return to the library another time.

TEENS AND TWEENS

For many teens and tweens, the library is a critical safe place. Staff and security need to keep in mind that between the ages of 10 and 30, the human brain undergoes enormous changes, and youngsters’ appearances don’t always match up with where they are developmentally. Teens in particular experience strong emotions without the ability to regulate them. “Even if they look grown, their brains aren’t,” said Alex Nyquist, pediatric psychologist at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine. Staff should adopt a compassionate, rather than punitive, approach when teens become disruptive—giving kids clear expectations and explanations, coaching them toward desired behavior, and offering second chances when they make mistakes.

As with all patrons, building relationships with youth is key to keeping the peace, but the dynamic is different. Teens often hang out in groups, and an adult should begin by talking to them together, noted Nikky Robinson, outreach and connections coordinator at Star House, an Ohio drop-in center for youth experiencing homelessness. Keep it professional, be mindful of their body language, give them their space, and always thank them for their time, she added.

Creating an intentional space, and then fostering a sense of ownership for the teens who use it, can go a long way. At Oak Park Public Library, IL, teens were allowed to decorate and design the logo for their space, said Director of Equity and Anti-Racism Stephen Jackson.

Remember—as minors, they may not be in a position to advocate for themselves and may need an advocate in a difficult situation. If a teen is brave enough to share a traumatic experience, let them know you believe them and that what happened isn’t okay, said Nyquist. And if you anticipate they are about to disclose something traumatic, added Jackson, make sure to remind them that library employees are mandated to report that information. If a report needs to be filed, invite the teen into the process to give them agency over the situation and lessen the chances of it retraumatizing them.

Most important, if you misstep—get angry, or miss an important cue—apologize. “If you say, ‘You’re right, I was wrong, and I hurt you,’ ” that can diffuse a tense situation, said Nyquist.

WHEN THE WORST HAPPENS

Security incidents will happen no matter how conscientiously a library plans to prevent them. The way leadership handles these events after the fact—communicating, debriefing, and addressing the trauma of those affected—can make all the difference. Clear delineation of roles and responsibilities is key, as is communicating with staff as much and as early as possible after an incident. As with other guidelines, emergency policies and procedures should be set ahead of time by a multidisciplinary task force made up of the library’s security team, other front-line workers, and union reps, among others. Make sure staff are trained and are equipped with the correct resources, such as communication templates and incident-reporting tools. A system for debriefing and checking in with staff must be clearly established well before a crisis happens. Policies and procedures only work if they reflect current realities, so they should be assessed, and revised if necessary, after any incident and as circumstances change.

However, policies can’t manage everything staff and the public will be experiencing, such as fear, anger, and grief.

When librarian Amber Clarke was killed in the parking lot of the Sacramento Public Library in December 2018, the tragedy deeply shook her coworkers, friends, and patrons. But because of a shooting in the library in 1993, in which two staff members were killed, the library had comprehensive safety and security policies in place, and all employees had been through emergency-preparedness training. What that meant, said Deputy Director of Support Services Jarrid Keller, was that the chain and methods of communication were set in advance, resources for staff care were available, plans for the continuity of operations existed, and what happened was documented appropriately. Nevertheless, leadership received criticism about how it was handled, both from within the library and from the community. Out of that process emerged two new support resources—a customer-care team and a threat assessment team.

|

DEDICATED SPACE Oak Park Public Library’s teen and tween space offers an intentional, secure area for them to read, play, and be themselves. Photo courtesy of Oak Park Library |

COMMUNITY RESPONSE

Communicating after a difficult or tragic event is all-hands-on-deck work. The public needs to be assured that the library is a safe space, said CML CEO Patrick Losinski. And that communication must be authentic—“These are operational responses, not marketing.”

It’s the library’s job to show up and have honest conversations about incidents, looking to residents for guidance on what needs to be discussed. Show—don’t tell—that the library is safe by inviting community members, business owners, and local leaders into the library to see for themselves.

After a 2019 shooting in the Cleveland Public Library, recalled Executive Director and CEO Felton Thomas, an outside group used it as an opportunity to portray the library as unsafe, claiming that the administration was out of touch with community needs. Thomas’s response was to make himself visible in the neighborhood every day, to focus on the community and the incident itself, and to take residents’ lead on what they wanted from the library. The answer, in this case, turned out to be adding more safety officers—a group that has since gotten accolades from staff. “What was a media crisis turned out to be exceptional for the library and the community,” he said.

THE CONVERSATION CONTINUES

The responses, resources, and ideas offered during the summit were just the beginning of an ongoing conversation about the many variables of keeping staff and patrons safe, how and when to engage with the library’s community on the subject, and adding as many voices into the mix as possible. There is no single answer for any of these issues. But sharing among peers, establishing best practices, maintaining a compassionate outlook, and taking proactive measures can help mitigate many security issues.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!