Robin DiAngelo on Confronting White Fragility | ALA Midwinter

Author and activist Robin DiAngelo explained that grappling with racism can be uncomfortable for white people—but it's crucial to dismantling systemic oppression.

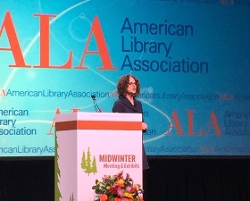

Discussing race can feel awkward. But according to antiracist activist and scholar Robin DiAngelo, who presented Loida Garcia-Febo’s President’s Program at the American Library Association’s recent Midwinter Meeting in Seattle, that discomfort is necessary, especially for those who, because of white privilege, are rarely forced to consider racism. She told participants, “If I do a good job in my very short time in front of you, this won’t be a comfortable hour for the white people.”

Discussing race can feel awkward. But according to antiracist activist and scholar Robin DiAngelo, who presented Loida Garcia-Febo’s President’s Program at the American Library Association’s recent Midwinter Meeting in Seattle, that discomfort is necessary, especially for those who, because of white privilege, are rarely forced to consider racism. She told participants, “If I do a good job in my very short time in front of you, this won’t be a comfortable hour for the white people.”

DiAngelo is intimately familiar with white people’s anxiety. She’s worked as an antiracist trainer for almost 20 years, and her book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People To Talk About Racism encapsulates much of what she’s learned—namely, that most white people are so used to seeing white as the default that being asked to grapple with their privilege causes extreme distress and anger.

People of color, she noted, are well aware of this response, or “white fragility,” so she directed much of her talk toward white listeners. “When I talk about ‘we’ and ‘us,’ when I use those terms, I’m talking to the vast majority of people in this room, the vast majority of librarians, and the vast majority of the people sitting at the tables, making decisions that will affect the lives of people who are not at those tables.”

DiAngelo kept her discussion lively and often funny, frequently making her points through examples from pop culture: a nearly all-white Miss Teen America pageant, or a college Jeopardy! program in which “African American history” remained the only unplayed category at the end of the game. Her humor, she explained, “helps relieve tension, helps white folks maybe not take ourselves so seriously.”

She emphasized that U.S. culture—and the culture of any white, settler nation—offers white people no substantial education on the subject of race. Though that doesn’t keep white people from sharing their opinions, “if you have not devoted years of sustained study focused on this topic, your opinions are necessarily superficial and uninformed.”

She dismantled misconceptions about racism.

“What is the mainstream definition of a racist?” she asked. “It is an individual who consciously does not like somebody based on race and is intentionally mean to them.” Viewing racism as a deliberate act, DiAngelo noted, allows well-intentioned white people to avoid labeling their own behavior as racist. It also leads to defensiveness and derailing when white people are told their words or actions are racist, because they often focus on denying what they hear as an accusation of being a consciously bad person. Rather they should be fixing the harm that they (perhaps unintentionally and even unconsciously) have caused or perpetuated—something white people can’t avoid, because, as DiAngelo noted, “nothing can and nothing did exempt” them from the experience of being white in a society that privileges whiteness, including loving people of color and experiencing other oppressions (such as those based on gender, class, religion, or sexual orientation).

Instead, she argued, “Racism is a system. Not an event.” All people of color experience racism “in shared and specific ways,” but antiblackness is especially pervasive. DiAngelo cited the history of institutional oppression toward black people in the United States: slavery, the denial of voter rights, mass incarceration, the school-to-prison pipeline, and much more.

That’s why, she says, although individual people of color may be biased against white people, “African Americans are not and have never been in a position to do this to the white collective; the white collective has always been and continues to be in the position to do this to African Americans.”

She added, to applause, “There is no such thing as reverse racism.”

DiAngelo took aim at another convenient misconception: that racists are old, mean-spirited, Southern, and ignorant, and that young, educated progressives aren’t racist. White progressives, she argued, “cause the most daily toxicity to people of color. Because we’re most likely to be around them, but we can be incredibly arrogant and certain and unwilling to examine to any degree the way that we perpetrate racism.”

Participants were asked to consider race from the perspective of their 13-year-old self: How racially diverse was your neighborhood? Where did black people live if they did not live in your neighborhood? What were the characteristics of a good school? What kind of student went to a good school?

She also asked the audience to think about ways in which race has shaped their lives. “My experience is that most white people cannot answer that question,” she said. “We bring that inability to think critically about our own race to the table with us, and it actually can create a hostile environment for people of color living in predominantly white spaces.”

DiAngelo added, “People of color who are in predominantly white spaces spend an inordinate amount of energy trying to keep white people racially comfortable, because we cannot handle being unsettled racially. We have very little skills for that.” As a result, people of color often don’t tell white people when their behavior is hurtful, because managing white people’s responses is too overwhelming.

DiAngelo pushed audience members to develop humility: “If you’re white and you’re sitting there right now thinking, ‘Oh my god, I wonder if that’s me?’ Yes, it is.”

Displaying a slide with an image of a dock, DiAngelo used the structure as a metaphor for how U.S. culture sees racism. Though the dock appears to be floating on the water, it’s held up by pillars underneath—just as the superficial remarks that many white people make about race belie an entire system of oppression and allow white people to stop engaging with ideas that threaten their worldview.

“I was taught to treat everyone the same” is a comment DiAngelo hears from many white people; others tell her that they can’t be racist because friends, family, or coworkers are people of color.

DiAngelo dryly debunked the idea that proximity equals understanding. “I’m married to a man. And the day he fell in love with me, his sexism did not vanish.”

She showed participants images, from religious iconography to photos of politicians to pictures of weddings, funerals, churches—all of which cemented the idea that whiteness is the default. “This is the water of white superiority, white supremacy, white as the ideal for humanity. These messages are weighing down on every one of us, 24/7. There are no umbrellas.”

This culture is why white people lash out when confronted with their own whiteness or privilege, along with a belief that to consider them as part of a group is to diminish their individuality (but not, often, the individuality of people of color). DiAngelo clarified the term white fragility. “We’re fragile in our sensibilities…but we are not fragile at all in the impact that it has, because we have the weight of history and institutional power behind us.” White fragility is “weaponized tears. Weaponized defensiveness,” which has the power to shut down conversations that make white people uncomfortable and penalize the people who start them.

She pushed audience members to check their own privilege. She displayed an image of all white male House of Representatives at a table and asked women to consider how welcome they’d feel joining that discussion. She quickly followed that up with a photograph of a group of white women at a table and asked whether women of color would feel welcome in that space.

“White women, we don’t land any more lightly on people of color. We have not historically been good allies in any consistent way. We are not free of racism because we suffer from sexism and patriarchy.” In fact, she said, the impact of racism from white women can be worse, because they have a “way in” to understanding racism by analogy, and often choose instead to use it as a “way out,” to absolve themselves of needing to do so.

While combating oppression will necessarily unsettle the worldview that white people hold, it’s crucial, DiAngelo said. “Racism hurts, even kills people of color 24/7. Interrupting it is more important than my feelings, ego, or self-image.”

DiAngelo closed by once more stressing the lack of education that white people receive around race and whiteness. “That is why you play such a critical role as librarians, as people who provide...education to basically everyone,” She said. “I know you are commited to this work.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Dorothy Dorothy

I understand the need to confront this, but as you stated, white people inherently don't have the tools. I think we need some advice in how to engage and react in a genuine way. You have given us food for thought, now please give us examples and help us with some tools. I admit I'm a fragile liberal, but I want to do the right thing. I have experienced the anger of black people who don't want me to exist. I want to to be able to confront that in an acceptable way.Posted : Feb 15, 2019 07:30