Vital and Visible: Academic Librarians Lead On Distance Learning

When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down campuses, libraries helped salvage spring semesters by supporting distance learning. Plans for fall remain in limbo, but academic librarians share what they’ve learned.

|

In the original version of this article, we omitted mention that Gale, a Cengage Company, sponsored LJ's Academic COVID-19 Response Survey. Library Journal regrets the error. At press time, the results of the survey were still in progress. After adjusting for duplicate answers and final responses, the number of responses was 414, rather than 552. For a complimentary report on the final survey, follow this link. |

When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down campuses, libraries helped salvage spring semesters by supporting distance learning. Plans for fall remain in limbo, but academic librarians share what they’ve learned

It has been a difficult spring for higher ed, as colleges and universities had to abruptly move classes online and students off-site to control the coronavirus. A lot of students were, predictably, unhappy with the results.

It has been a difficult spring for higher ed, as colleges and universities had to abruptly move classes online and students off-site to control the coronavirus. A lot of students were, predictably, unhappy with the results.

At press time, class-action lawsuits had been filed against more than two dozen higher-ed institutions—including Brown, Cornell, Columbia, and Michigan State—demanding refunds for tuition and fees.

The lawsuits cite students’ inability to complete hands-on projects without access to labs and other facilities, but also describe a general decline in the quality of courses taken online.

“You just feel a little bit diminished,” Grainger Rickenbaker, a freshman who filed a class-action lawsuit against Drexel University, told the Associated Press. Online courses, he said, are “just not the same experience I would be getting if I was at the campus.”

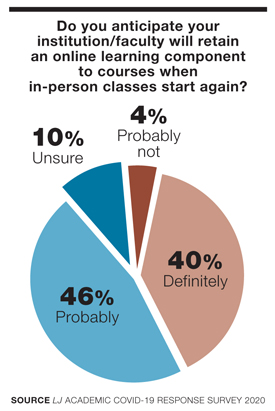

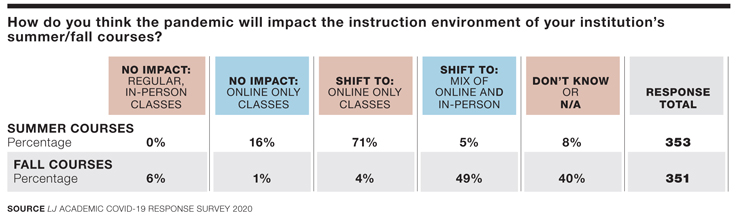

With the fall semester fast approaching, higher ed institutions are struggling to determine whether they will open in person in the fall, stay 100 percent online, or take a hybrid approach. Last month, California State University became the first major system to announce that all of its campuses would remain closed through the fall semester. At press time, most other institutions were grappling with similar decisions. And even those planning to open in person must make contingency plans for a possible second wave which might send students home and classes online once again.

But an online fall semester need not be a repeat. With more time to plan and the experience of trial by fire under their belts, instructors can create engaging online content, and plenty of platforms enable one-on-one or small group meetings over video conference. Academic librarians, in many cases, have helped stem chaos and maintain quality control for instructors and students. Their takeaways will help inform how libraries support and shape distance learning long past the pandemic.

READY TO GO

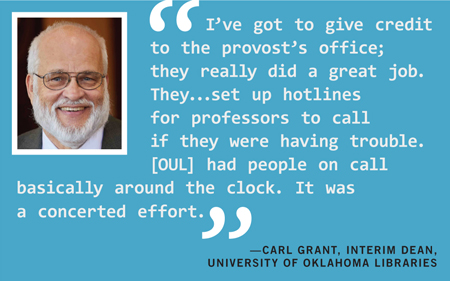

For the past seven years, the University of Oklahoma Libraries (OUL) has been working to create “an equal experience” between in-person and online settings, according to Interim Dean Carl Grant. Thus, they “were very well positioned to flip the switch,” when campus shut down.

OUL librarians helped faculty and other colleagues get set up to work remotely and ensured they had access to resources they needed. Grant describes mixed levels of preparedness, including instructors who had rarely done more than post a syllabus onto the university’s Canvas learning management system (LMS).

“I’ve got to give credit to the provosts’ office; they really did a great job,” Grant says. “They…set up hotlines for professors to call if they were having trouble. [OUL] had people on call basically around the clock. There was a concerted effort.”

“I’ve got to give credit to the provosts’ office; they really did a great job,” Grant says. “They…set up hotlines for professors to call if they were having trouble. [OUL] had people on call basically around the clock. There was a concerted effort.”

Grant cites multiple examples, noting that the library had quickly worked with two other departments on campus to recreate the university’s 32nd annual Undergraduate Research Day in an online environment. In fact, this year’s research day set a new record, drawing 142 video submissions from undergraduates in multiple disciplines.

Separately, OUL’s Informatics Department worked with computer science instructors to translate capstone courses into an online classroom environment. And by May its Data Analytics, Visualization & Informatics Syndicate (DAVIS) and Digital Scholarship lab had already taught two hands-on data visualization workshops via Zoom, with more planned through the remainder of the semester.

DAVIS has been “exploring the idea of opening up their online sessions to those outside of our university community” as well, Grant says. “If this goes well, it might be a concept other units within OUL would consider. Perhaps, as [higher education] faces aspects of the future, this might be a way to build collaboration, while expanding offerings, if we could get other institutions to do the same.”

SOMEWHAT PREPARED

OUL’s is one of the better case scenarios. LJ’s Academic COVID-19 Response Survey—sponsored by Gale, a Cengage Company—currently in the field and nearly complete, corroborated Grant’s description of mixed levels of preparedness among instructors. Collectively, academic librarian respondents said that 20 percent of higher-ed faculty were “not prepared at all” for teaching in a distance learning environment prior to the COVID-19 crisis, while about 68 percent were “somewhat prepared.” Only 10 percent of respondents said faculty were “prepared,” and only two percent described faculty as “very prepared.”

“The disciplines which already had robust online-only course offerings (typically STEM) had the necessary infrastructure and pedagogies in place. Everyone else suddenly had to catch up on 10 years’ worth of online instruction development and best practices,” one respondent wrote.

Another said that “we have quite a few long-time faculty members who have never taught online and who do not and never have used Moodle,” the school’s LMS. Getting these faculty trained suddenly became a major priority, and library staff “spent a LOT of time helping them find e-resources to use in place of DVDs they show in class or other materials they shared in physical formats.”

Michael Stephens, associate professor for the School of Information at San José State University, who has taught online exclusively for the past decade, notes that academic libraries should anticipate these training and service needs going forward, especially if campuses remain closed through fall or transition to hybrid online/in-person instruction models while social distancing protocols remain in place.

“Professors shouldn’t just be told ‘we’ll see you in a week with your online lectures,’” he says. “There has to be some training or guidance,” presenting an opportunity for libraries to step into that role.

Large lecture hall classes are already prime candidates for a shift to a flipped classroom model, he suggests. Lectures could either be pre-recorded or delivered live online, and students would then meet in small groups to work on projects or problem solving. Librarians could be embedded in these courses to provide online research assistance.

“The beauty of it is that it works better anyway,” Stephens says. “We waste a lot of time getting to campus to sit in a room with 300 other people.”

Unfortunately, several of the survey’s 414 respondents, who were primarily librarians at four-year colleges and universities, noted that there were also many programs with hands-on or in-person components—ranging from science labs to music and theater to welding courses at one community college—that would require “creative or impossible changes” to take online, as one librarian wrote.

WHAT WORKS

Many respondents noted that campus shutdowns had made the library’s digital resources both more vital and more visible to faculty and students. Students were discovering services such as virtual research appointments using WebEx or other platforms. Services such as text chat, which were already popular, had been more heavily used, and multiple respondents also reported that use of traditional online tools such as LibGuides, tutorials, FAQs, and email assistance had been rising as well.

“Our library was already offering a variety of virtual services in order to equitably serve our users who aren’t on campus, are learning online, or can’t come to the library during regular hours,” one respondent wrote. “Prioritizing the development of these options over the last few years put us in an excellent position to pivot to all-online service delivery when our campus closed. These include: online synchronous library instruction sessions, 24/7 chat reference, [and] virtual reference (video meetings) with scheduling availability outside of regular hours.”

Basic adjustments to the library’s website and catalog had been helpful, several respondents said. Library homepages were redesigned to highlight e-resources and online services, while catalogs were switched to search online offerings by default. “If students or faculty find a physical volume in the catalog through known item searching, then the option is...to email [a] request to our ref desk and then we try to find a digital alternative,” one respondent wrote.

OPEN—FOR NOW

OPEN—FOR NOW

Recognizing the unprecedented challenges posed by the sudden campus shutdowns, dozens of publishers, vendors, and academic presses have lifted paywalls and made e-textbooks, monographs, databases, and other content free to access through June. In order to make that content discoverable, staff at libraries such as OUL “have been working diligently to add metadata records for the growing number of full-text databases to which we are receiving temporary open access while the library is closed,” Grant says.

And in April, HathiTrust announced Emergency Temporary Access Service for member libraries experiencing “unexpected or involuntary, temporary disruptions” to service due to COVID-19 related closures. The service temporarily enables member library patrons “to obtain lawful access to specific digital materials in HathiTrust that correspond to physical books held by their own library.”

However, at press time, free access to many of these resources was scheduled to end this summer. Survey respondents were already anticipating challenges.

“We have a heavily used textbook collection that became inaccessible with the move to remote instruction and the close of the library,” one respondent wrote. “Publishers making content freely available through VitalSource has been extremely helpful but that ends this term. In the summer and fall, I expect some of the physical collection will still be inaccessible and the question becomes how the library can support students and faculty with e-texts/OERs [open educational resources].”

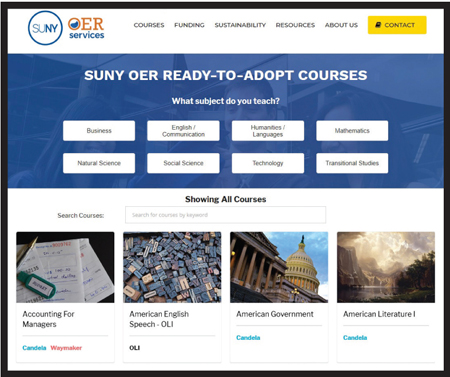

During “The Impact of Distance Learning on the Academic Library,” a webcast sponsored by Ex Libris and hosted by Library Journal on April 28, panelist Timothy Jackson, resource sharing and fulfillment program manager for the State University of New York (SUNY) Shared Library Services, said that OER has been “a godsend during this current crisis.”

SUNY has put a lot of effort into OER during the past decade, beginning with the creation of the Open SUNY Textbook Project in 2012, led by SUNY Geneseo’s Milne Library, and the establishment SUNY OER Services (SOS) in 2016, which has facilitated OER adoption and creation throughout the SUNY system. Jackson said that OER has been adopted in more than 4,000 classes attended by more than 100,000 enrolled students.

SOS was “designed mainly to address concerns about textbook affordability and the impact that has on student success,” Jackson said. However, “in this current situation, it has helped decrease the reliance on physical textbooks and traditional print materials.” As SUNY considers the possibility of closed campuses or limited campus services during the fall semester, the Shared Library Services division is working to shift additional courses away from print textbooks to open free textbooks, he said.

OBSTRUCTIONS AHEAD

OBSTRUCTIONS AHEAD

Several respondents wrote that having librarians embedded in online, research-intensive courses was on their wish lists, but the idea had unfortunately failed to gain traction with library administrators or faculty.

Just under 40 percent of respondents said that library staff were embedded in online classes at their institutions. This ranked last among services listed—behind directing students to digital resources (93 percent), aiding students conducting research (93 percent), providing technical assistance to students (69 percent), licensing additional ebooks and ejournals (68 percent), helping align library content to courses and curriculum (62 percent), and offering guidance on copyright/fair use (56 percent).

“I would like for the library to be more involved in assisting faculty, but our offers to provide support have not been taken,” one librarian wrote. “Our library administrator has not been effective at promoting our library, so I am not sure that other departments understand our value.” The respondent had provided embedded support for one series of courses, but felt that the concept was not catching on with colleagues or instructors, possibly because of concerns that these new arrangements would demand more work or time.

Many respondents also complained about impediments that prevented integrating library resources into online courses.

“We have been trying for years to include a widget of the library catalog, discovery services, and virtual reference on every online course but our attempts have been unsuccessful,” one respondent wrote. Another explained that “I don’t have access to Blackboard [LMS] in the capacity that would be helpful for giving aid to students. I have student access, but…I can’t create videos, host virtual classes, or upload content that could help students with research and other library services.”

Yet another described a similar tiered access model that prevented them from adding e-resources to their university’s Moodle LMS. “I have to request permission from our LMS admin and often wait quite a while to get it. We have new services, like chat reference, but I can’t add them to our pages because we switched to a new portal in the fall before IT worked out all the kinks with it. I used to be able to add code [and] scripting…now I can’t, and the person in charge doesn’t know enough about the technical aspects of the new portal to provide quick assistance.”

One problem that came up repeatedly in written comments—libraries are short-staffed and budgets are already stretched thin, which heightens concerns about overcommitting to new or enhanced online services. When asked to name the barriers their library faced to enhance ongoing remote access and online learning, 53 percent of respondents said funding, 35 percent said lack of time, and 35 percent said that their current infrastructure and systems were inadequate. Faculty readiness—an issue that could presumably be remedied with time and money—was also listed by 51 percent of respondents.

Unfortunately, the pandemic has greatly slowed the national economy, states and municipalities are already dealing with massive budgetary shortfalls, and the crisis is not yet resolved. Public support for higher education is likely to decline at the same time that enrollments are falling as many incoming freshmen defer enrollment or take a gap year, whether because of concerns about getting sick (at in-person campuses), missing the in-person experience (for those starting online), inability to enter the country (for international students who often pay full freight), or economic challenges (for the many families impacted by rising unemployment). As a result, higher education budgets will face even more pressures in the coming months and years. Library leaders will need to get in front of conversations about consolidation and reduction of services; pointing out barriers to collaboration could be one way to propose budget-friendly service enhancements.

|

ALWAYS OPEN The State University of New York’s OER program has been “a godsend” during the crisis |

ACCESS ISSUES

In 2019, the Pew Research Center reported that 44 percent of adults in households with incomes below $33,000 don’t have access to broadband internet. A separate analysis by Microsoft estimated that the number of Americans without access to download speeds of at least 25 megabytes per second may be over 163 million. At colleges and universities, it’s often taken for granted that students have access to online courses and e-resources via computer labs. But with labs—many of which are in libraries—closed, the current crisis has revealed that many students are left behind when courses are moved online.

“We’ve had issues with students who don’t have access to computers, the internet, or books they need,” wrote one respondent to LJ’s survey.

It’s not just students. One survey respondent noted that many tutors are also facing access issues. One can only assume that some faculty live in areas poorly served by commercial internet service providers as well—and that adjuncts and graduate teaching assistants may not be able to afford home broadband even where it’s available.

Grant says that most OUL staff had not experienced connectivity problems, but that it had been an issue for a few. “If you don’t live in Norman [OK], it gets rural pretty fast,” he said. Prior to shutting down, the library had taken carts of laptops usually used within library locations and loaned them to students and staff, along with dozens of Wi-Fi hotspots for people with broadband access issues.

Some colleges provide all incoming freshmen with tablets or laptops, and Stephens suggested that these programs would need to become much more widespread if instruction and services remain online.

“Give them a laptop and hotspot as they enroll, so you don’t have a campus where one-third of your students don’t have broadband at home…. One thing the virus has done is expose so many inequalities,” he says.

TAKE CARE

During “The Impact of Distance Learning on the Academic Library” webcast, every panelist discussed the impact that the pandemic has had on library staff, and the importance of helping staff manage the emotional stress.

“It’s vital to remember that staff are going through this along with everyone else,” said Dennis M. Swanson, dean of the Livermore Library at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. Leaders should check in “not just about the job, [but about any] personal needs that we can help with or help them attend to. They’re people like everyone else.”

Danuta A. Nitecki, dean of libraries, and professor, College of Computing & Informatics for Drexel University Libraries, said that informal all-staff Zoom meetings were a good way to help everyone stay in touch. And Elijah Scott, executive director of the Florida Academic Library Services Cooperative, suggested “virtual coffee breaks” where someone would leave a meeting open in the afternoon for staff to “step in and step out a few times a week” with no agenda or set topics for discussion.

Separately, Grant tells LJ that OUL is sending staff short surveys every week, enabling them to submit anonymous questions, concerns, or complaints. Library leaders then review these submissions prior to a weekly Zoom meeting.

“There’s no question that it’s been hard for the library team to go from working in the building to working remotely,” Grant says. “We want to know what issues they’re having, and they shouldn’t have to raise them during a live forum. You have to reassure your people that these are things we all understand.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!