Missing the Mark: Time To Refocus Our Advocacy Approach | Editorial

If you haven’t yet read From Awareness to Funding: Voter Perceptions and Support of Public Libraries in 2018, please put it on the top of your to-do list. Released in March by the Public Library Association (PLA) and the American Library Association Office for Library Advocacy, in partnership with OCLC, it updates the findings of the initial Awareness to Funding report done in 2008 with startling insights into how voters connect to libraries or—more concerning—increasingly don’t.

If you haven’t yet read From Awareness to Funding: Voter Perceptions and Support of Public Libraries in 2018, please put it on the top of your to-do list. Released in March by the Public Library Association (PLA) and the American Library Association Office for Library Advocacy, in partnership with OCLC, it updates the findings of the initial Awareness to Funding report done in 2008 with startling insights into how voters connect to libraries or—more concerning—increasingly don’t.

EveryLibrary’s John Chrastka (a 2014 LJ Mover & Shaker [M&S]) tunes us in to some of the conclusions and reflects on a primary takeaway in “Reversing the Slide in Voter Support." He urges a tactical shift in library advocacy. “Our core messaging and value propositions have taken a massive hit,” he writes, noting, among other findings, that fewer people think that “if the library were to shut down, something essential would be lost”—down to 55% today from 71% a decade ago.

Also on the alert is Chrastka’s EveryLibrary colleague Patrick Sweeney (a 2015 M&S). In “The Data Is Clear, It’s Time To Move Beyond Storytelling for Library Advocacy,” he explores the critical distinction between someone who generally supports libraries and someone moved by political will to go out and vote to support them.

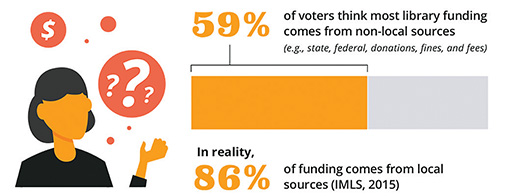

This leads me to reflect on one finding that seems particularly problematic: people don’t know how public libraries are funded. A full 59% of voters, according to the study, think the bulk of library funding comes from somewhere other than their local taxes—see graphic—when 86% of funding is local. We have some basic work to do here. Voters should feel engagement, and agency, when it comes to the vitality of their own library. They should know that it is theirs, not some entity gifted by a distant hand. When we consider how well libraries do at the ballot box when they go out for referenda, I can’t help but think we can make progress if we encourage individuals to see their role at home. It’s a failure to communicate when potential supporters don’t realize their action matters directly—and that inaction puts something beloved, and fundamentally important, at risk.

It’s critical to articulate and convey just what is at stake. Writing on her library’s blog, Vailey Oehlke, director of the Multnomah County Library, OR, and a past PLA president, notes the report’s findings “call for urgent action.” Exploring a number of factors in play, she arrives at a proposal to update an “equation” she argues libraries have depended on for a long time, shifting from “if books = important; and library = books; then libraries = important” to “if libraries = democracy; and democracy = important; then libraries = important.”

It’s disappointing to think that all the experience the field has gained on the advocacy front is missing the mark. That experience has been valuable, but it’s not enough. If we can’t accept that fact and adapt, we risk complacency. [Side reading: as Francesca Gina recently illustrated in Scientific American, people who rely on their sense of success may not make good calls on key decisions.] Instead, let’s confront this reality check, and find ways to inspire political action as well as affection.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Valerie J. Gross

What a timely editorial. Thank you, Rebecca! Indeed, everyone in the library profession would do well to heed John Chrastka’s suggestion to “acknowledge that more than a decade of advocacy campaigns have failed” and that we must change our approach to “do it right.” If further evidence is needed, Google “Wikipedia Douglas County Library System.” Expect to be stunned by the opening sentence: “The Douglas County Library System was a public library system” in Oregon. The good news is that there is a simple solution. It involves a new way of thinking and modified language. It’s called “Libraries = Education.” Why does it work? Because it causes those outside the profession to fully understand what we do (see bit.ly/LibEduMI2010 for a video clip of Salem-South Lyon District (MI) Library’s success with the approach on elected officials—the result is astounding). The strategy applies to all library types. It establishes a crystal clear purpose for our profession and dispels—permanently—all misperceptions. Use it and you’ll never again have to explain what you do or “tell your story.” This is because the very language you’ll use will speak for itself. Hundreds of libraries across the U.S. have adopted the concepts and enjoy heightened respect and optimal funding. What are they doing differently? They are: Repositioning public libraries as educational institutions (school/academic/special libraries as key departments), and librarians as educators Categorizing all that their libraries do under three, easy-to-remember “pillars”: I. Self-Directed Education (our collections); II. Research Assistance & Instruction (classes, seminars and workshops for all ages, taught by “Research Specialists” and library “Instructors”); III. Instructive & Enlightening Experiences (events, partnerships, and building community) Replacing traditional terminology with language people outside of the field understand (e.g., “education,” “instruction,” and “research” replace words like “information” and “reference;” “class” takes the place of “story time” and “program,” and “curriculum” replaces the unremarkable “services”). It goes like this. The next time someone asks you what your library does, say, “We deliver equal opportunity in education for all through a curriculum that comprises Three Pillars: Self-Directed Education, Research Assistance & Instruction, and Instructive & Enlightening Experiences.” They’ll first say, “Wow!”, and then, “Of course!” (because you’re telling them what they already know). There are three types of education: K-12 Education, Higher Education, and Library Education (see diagram at bit.ly/LibEduDiagram). While Library Education can also involve formal education that leads to a degree, it is chiefly informal education defined as follows: information about a subject matter knowledge acquired by learning the process of acquiring knowledge, and an enlightening experience. For a complete presentation of Libraries = Education, see Transforming our Image, Building Our Brand: The Education Advantage, ABC-CLIO. (San Jose State University uses the book in its MLIS program; it's required reading for Chicago Public Library staff.) The Three Pillars image—which could become our refreshed national symbol—is available at bit.ly/LibEduThreePillars and includes a button template. Perhaps now is the time for ALA to adopt Libraries = Education. Consider encouraging them to do so. You’ll be ensuring a solid future for libraries and librarianship for centuries to come.Posted : May 30, 2018 07:10