Mary SanGiovanni on Lovecraftian & Cosmic Horror: A Primer for Library Workers

Author, podcaster, and Cosmic Horror expert Mary SanGiovanni discusses the long reach of H.P. Lovecraft in order to help library workers better understand his legacy and the popular subgenre he created.

Recently, Becky sat down [virtually] with author, podcaster, and Cosmic Horror expert Mary SanGiovanni to discuss the long reach of H.P. Lovecraft in order to help library workers better understand his legacy and the popular subgenre he created.

Recently, Becky sat down [virtually] with author, podcaster, and Cosmic Horror expert Mary SanGiovanni to discuss the long reach of H.P. Lovecraft in order to help library workers better understand his legacy and the popular subgenre he created.

Let's start at the beginning. What IS Cosmic Horror? How does Lovecraft the man, and his legacy as a writer shape that definition? And why now, 100 years later is cosmic horror so popular with a mainstream audience?

To me, Cosmic Horror is a subgenre primarily characterized by the scope of the horror presented. In Cosmic Horror, there is a sense that the antagonistic force, whether evil or just utterly indifferent, is so pervasive and powerful, and of such a size and scope, that its very existence dwarfs the significance of humanity. This force is nearly always supernatural, but echoes the power of natural forces like oceans, storms, black holes, deep space, etc., and in fact, those natural forces are often a part of the setting where the entity makes contact with our natural world.

Cosmic horror stories often have an underlying theme of nihilism, in that humanity, when trying to go up against such forces, is woefully unprepared and unmatched, and will most certainly lose—if not now, then eventually. Some modern cosmic horror reframes that nihilism and insignificance of humanity by making a satisfying resolution of the hero achieving a goal that he or she believes to be bigger than oneself.

There is also the theme of insanity, present in nearly every Cosmic Horror story in a literal or figurative sense; this is often done in conjunction with an ever-present theme that reality is no longer what we thought it was—if it ever had been at all. There is the existence of other dimensions, worlds and spaces between dimensions, etc. I believe this is meant to further reinforce the scope of the antagonistic force and give some scientific explanation for its origin.

There is a misanthropy as well, which reinforces the notion that we are not only not alone in the universe, but far from central or important to it. Finally, there is a theme of transformation and transcendence—this can (and often is) displayed as physical changes to the body, but is also shown through profound changes to the mind (the growing insanity) and the soul. The characters in Cosmic Horror stories often resist the changes, only to find themselves succumbing, for better or worse, in the end.

There are tropes that often appear in classic Cosmic Horror that are either used traditionally for effect, or more often in modern Cosmic Horror, subverted for greater effect. These tropes include the presence of cults devoted almost mindlessly to this great antagonistic force, ancient tomes that reveal age-old secrets about that force, the forbidden quest for knowledge that ultimately proves to be the quester's undoing, detachment/isolation of a socially introverted main character, and feelings of helplessness at the revelation of some awful, unforgettable, undeniable truth. And of course, there are often tentacles. Lovecraft's monsters were often described as connected in some way to the sea, and both the sights and sounds of these creatures, as well as the evidence they left behind, were often described in terms often used in relation to the alien aspects of sea creatures.

And speaking of Lovecraft, many of his own fears, insecurities, beliefs, prejudices, and quirks are responsible for recurring elements in his writing. His stories often featured a strong fear of the "Other," whether that be immigrants, aliens, outside forces from other dimensions, etc., and the decay of what he considered familiar, safe, and noble. Lovecraft led a difficult and sheltered life which, despite his healthy circle of pen pals, left him with some loathsome prejudices and some unpleasant fears about the future and about the charmed, antiquated New England environment he loved. He has been described as a man born after his time, and to an extent, that may be true; his language and his sense of small-town tradition reflect an older time. He was an atheist who enjoyed reading about the occult, witchcraft, and old religions, and even though his later works reflect a scientific framework which he believed relegated his pantheon from the supernatural to the natural, all his stories have elements of the occult running through them.

I think the popularity of cosmic horror persists today because at heart, humanity does fear otherness or being othered, and it often fears change which might propel us toward the unknown. However, most modern cosmic horror seeks to redefine what "Other" might be, and to subvert the racism and prejudices Lovecraft held and reclaim the genre in new and interesting ways.

What are some popular misconceptions about Lovecraft?

Most often, the misconceptions I see about Lovecraft's work are that it is old, stuffy, outdated, vague, and no longer relevant to today's more sophisticated and perhaps jaded society. This simply isn't true. While Lovecraft himself may have been those things, his work, and more importantly, the Cosmic Horror works that have come after, are certainly not. It's true that a lot of Cosmic Horror stories take place in an older era (usually the 1920s or 1930s, when Lovecraft lived and when his works were set). However, there is just as much Cosmic Horror that takes place in modern day. There is, perhaps, an addressing of tradition, of old values, of generations of old families, and of vague, nebulous things that go bump in the night. But these often create a backdrop to the vivid, even the visceral, to the modern, both magical and scientific, and to the very things with which we are concerned today in modern society.

Most often, the misconceptions I see about Lovecraft's work are that it is old, stuffy, outdated, vague, and no longer relevant to today's more sophisticated and perhaps jaded society. This simply isn't true. While Lovecraft himself may have been those things, his work, and more importantly, the Cosmic Horror works that have come after, are certainly not. It's true that a lot of Cosmic Horror stories take place in an older era (usually the 1920s or 1930s, when Lovecraft lived and when his works were set). However, there is just as much Cosmic Horror that takes place in modern day. There is, perhaps, an addressing of tradition, of old values, of generations of old families, and of vague, nebulous things that go bump in the night. But these often create a backdrop to the vivid, even the visceral, to the modern, both magical and scientific, and to the very things with which we are concerned today in modern society.

Cosmic Horror has itself a kind of transcendent flexibility in structure that allows for far more innovation than even Lovecraft could have ever dreamed, with his rigid beliefs and tightly disciplined style. Elements of Lovecraft's legacy are everywhere in pop culture—in music (Metallica and Black Sabbath, among countless other heavy metal and rock bands), in video games like Terraria and Fallout, in television, such as in South Park and the more recent Lovecraft Country, in tabletop games like Arkham Horror and Magic: The Gathering, toys, clothes, jewelry, and even home decor. The name Cthulhu is recognized (even if folks can't pronounce it) all across pop culture as an icon to the strange, to that which is just outside the limit of our knowing.

As our experience, our developments in science and technology, and our desire to spread out across the galaxy grow, so does that need humans seem to have to believe in something bigger, something always out there for us to work toward understanding. As long as we continue to need mysteries to solve, mountains to climb, challenges to conquer, and worlds to explore, cosmic horror will be popular, with its promise of something greater than the greatest of human experiences.

What do you wish everyone knew about Lovecraft and Cosmic Horror? If you were in charge of the PR machine for the subgenre and its grandfather, how would you spin it?

I would address the issue of Lovecraft's racism first. He had undeniably abhorrent views about people, and that should be acknowledged. I would also address how those views put a face—the wrong face—on the essence of horror which makes his work significant. At the heart of it, Lovecraft was a xenophobe. Now, that doesn't excuse the racism. It doesn't make it okay. It is not—it wasn't then, and it isn't now. What it does give us, though, is a glimpse into the nature of his personal fears. He was afraid of anything new or different being introduced to the simplicity of his life and his routine. He was afraid of new people, new ideas, and new customs that would not only change the life he knew, but irrevocably destroy it, and I think, given his childhood, change was something he equated with fear and pain. He was afraid of being different, being lost, being caught in a world passing him by. If we only look at the broad generalities of Lovecraft's fears, particularly as filtered through his fiction, we see fear of death, fear of sickness and pain. We see fear of loss of ourselves and loss of loved ones. We see fear of losing control of our bodies and/or our minds, and losing our sense of safety and security. And we see fear of being on the outside of the love and compassion of fellow humans.

Lovecraft touched those nerves in a broader sense with his work, and that's where the legacy lies. To appreciate the lasting effect of Cosmic Horror, one has to go deep, to the heart of hate, the heart of fear, and understand what drives it. It's not his racism and phobia which make Lovecraft's work timeless; it's the naked, blatant, almost naive terror still inherent in the work even when the racism and phobia are stripped away. It's the clay of basic human fear that he happened to shape one way, and that modern Cosmic Horror writers have come to shape in new, inclusive, and diverse ways that continue to breathe new life into the genre. I believe modern Cosmic Horror writers have done a wonderful job of reclaiming the fundamentals of Cosmic Horror and fully exploring its nearly limitless possibilities for fear of the unknown.

Library workers love booklists. Can you give us a list of the key titles and authors from the past up to and including the present of the works you think showcase Cosmic Horror? Titles that libraries should have available for readers to access.

Literary movements of Romanticism and Science Fantasy fed into what would come to be known as Weird fiction, and then, more specifically, Cosmic Horror. Some early, pre-Lovecraftian works would fall into one of those categories, perhaps, but are also considered cosmic horror due to the scope of their antagonistic force and its ultimate diminishing effect on humanity's significance. Here are some works that I feel span both the history and the range of Cosmic Horror.

1) “The Horla” by Guy de Maupassant. This short story was published in 1887 after a much shorter version appeared in the newspaper Gil Blas in October 26, 1886. Although it doesn't check every box that traditional cosmic horror is defined by, it does, in my opinion, check enough that it is worthy of examination as a tale both influential to and exhibiting features of Cosmic Horror. As H.P. Lovecraft explains it in his essay "Supernatural Horror in Literature" (1927): “Relating the advent in France of an invisible being who lives on water and milk, sways the minds of others, and seems to be the vanguard of a horde of extra-terrestrial organisms arrived on earth to subjugate and overwhelm mankind, this tense narrative is perhaps without peer in its particular department.”

2) The King in Yellow by Robert W. Chambers. This collection of stories was published in 1895. Its first four stories especially—"The Repairer of Reputations," "The Mask," "In the Court of the Dragon," and "The Yellow Sign"—relate tales of madness, of a shadowy ancient entity and its semi-supernatural servants, of a kingdom possibly in another dimension and time, and of a play said to drive people insane before they can finish reading, watching, or performing it. The play, the eponymous "The King in Yellow," tells the story of the return of an ancient god-king who would see the destruction of all but his faithful.

3) The Great God Pan, a novella by Welsh writer Arthur Machen. A version of the story was published in the magazine The Whirlwind in 1890, and Machen revised and extended it for its book publication (together with another story, "The Inmost Light") in 1894. This story is one of those which explores the close relationship between the natural and the supernatural, the transformation of humans and those only partially human, and the correlation of events which leads to a bigger picture, a scope of horrors from another dimension of which the world has had only a taste.

4) The House on the Borderland by William Hope Hodgson. Published in 1908, it is a surreal account of a recluse's stay at a remote house, and his run-ins with hostile supernatural creatures and otherworldly dimensions across great spans of time.

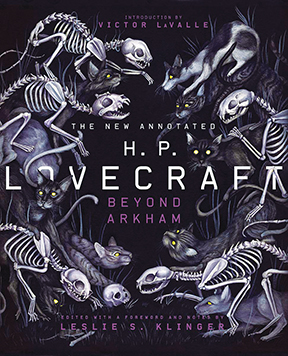

5) The Best of H.P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre by H.P. Lovecraft. While this particular volume of collected Lovecraft works was compiled by Del Rey in 1982, I feel it includes the best of Lovecraft's work, along with an intro by protege Robert Bloch (Psycho) and artwork which is indicative of the feel of Lovecraft's stories. The most significant Lovecraft stories, and the ones for which he is best known, are collected here.

6) The Inhabitant of the Lake and Less Welcome Tenants by Ramsey Campbell. Published in 1964 by Arkham House, this book was Campbell's first, the stories displaying his unique ability to both effectively write in the Cthulhu Mythos and also to add his own lasting mark to it. Campbell, a master of weird fiction and cosmic horror, would go on to excel beyond the realm of pastiche, but Lovecraft's influence is present in much of his work.

7) Songs of a Dead Dreamer by Thomas Ligotti, published in 1985 by Silver Scarab Press. Ligotti's collection of short fiction is considered a seminal work of cosmic horror and weird fiction. Much of Ligotti's work is darkly philosophical, even nihilistic, and he is considered a master of supernatural horror.

8) Move Underground by Nick Mamatas, published by Nightshade Books in 2004. A quirky combination of beat writing and Lovecraft mythos, this book tells the story of Jack Kerouac witnessing the rise og R'yleh, a famous city of the Old Ones in Lovecraft's mythos. He joins forces with Neal Cassady and William S. Burroughs on a cross-country trip to save America from a Cthulhu cult.

9) Darkness on the Edge of Town by Brian Keene, published in 2009 by Bloodletting Press. A story about a town cut off from the world by a wall of impenetrable darkness, it explores themes of isolation, insanity, human empathy, and survival in the face of the unknown.

10) The Croning by Laird Barron, published in 2012 by Nightshade books. Barron's debut novel of cosmic horror has black magic, cults, sanity-shattering revelations, and ancient entities, and the inexorable conclusions that these things will bring when aligned.

11) The Fisherman by John Langan, published by Word Horde in 2016. Langan's style is one of subtly mounting dread, which is the modus operandi of good Cosmic Horror. This book is a tale of deep loss and ancient secrets, and of dark places on the fringe of the known world.

12) The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle. Published by Tor in 2016, this story is, in essence, an answer to Lovecraft's especially racist short story, "The Horror at Red Hook." It takes place in New York City during the Jazz era, and evokes the crowded paranoia of the city and the racism of early 20th century America while including occult magic and dusty tomes, as well as a monstrous evil entity best left sleeping.

13) The Agents of Dreamland by Caitlyn Kiernan. Published by Tor in 2017, this story, as with much of Kiernan's work, is thoroughly cosmic horror in its tone and atmosphere. Told non-linearly, this novella contains a cult promising transcendence, contact from deep space, a woman floating outside of both time and space, and agents on the fringe of the unknown.

There really are so, so many other great cosmic horror novels, novellas, graphic novels, short stories, and more that I could name, but this is, in my opinion, an important list of prominent Cosmic Horror works.

What do you make of the recent trend of authors who are actively mining Lovecraft’s work as a starting point for their own work. Given Lovecraft’s history as a misanthrope, racist, misogynist, and homophobe, what do you make of the fact that many of those turning to Lovecraft for inspiration are the very people [women, people of color, and those in the LGBTQ community] who he despised.

I believe every time there is a development in science or technology, something that anchors or cements reality into place, the human race looks for something spiritual to believe in or to be afraid of. There seems to be an upswing of supernatural horror in general and Cosmic Horror in particular when people need an escape from the horrors of the real world—the very human atrocities we see in the news.

Despite, or maybe because of Lovecraft's flaws, I think the people writing modern cosmic horror today do so for a couple of reasons. For one, I think the universality of the subgenre he had such a hand in creating transcends his racism and phobias and speaks to the fears we all share as one people, as a species. I think there is an appeal in exploring the great unknown in this type of fiction, and the philosophical concepts of Cosmic Horror which are so much bigger than we are.

Second, I think in order to reconcile love for such a genre of limitless creative potential with the rigidity of the bigoted man who helped develop it, many of us are compelled to examine the subgenre and why it works, and to recreate, reform, redevelop it into something more vibrant, more viable, and more reflective of those endless possibilities. It is a genre with few boundaries, one which easily grows and changes and evolves. That's part of the beauty of the genre, and possibly the main reason why it has not only lasted as long as it has, but will continue on with each new writer's perspective and experiences.

How do you use Cosmic Horror in your own work? Why are you drawn to the tropes and themes as a writer? How do you reconcile the man with his continuing influence on some of the best and most popular horror we have today.

I have always loved monster stories, and before I fully understood that my work had a definite Cosmic Horror slant, I considered myself a writer of the supernatural, of weird tales of monsters from other dimensions. I always loved the idea of something existing out beyond the boundaries of the known universe—other dimensions, other planes of existence, other forms of being. I have always preferred the fantastic. To me, a life devoid of magic and mystery is dry and dull and boring, and I can't reconcile the God or universe I was taught to believe in growing up with the static boundary of reality as we know it now. I think what we know is only a small part of a bigger picture. To me, Cosmic Horror embraces those ideas and philosophies. It promises worlds beyond worlds, creatures from a limitless imagination of some higher intelligence, great vistas of the unexplored, and the magic that made the daunting journey through childhood worth travelling. I know that Cosmic Horror espouses hopelessness, madness, and the evil or indifferent character of godlike forces, but to me, there is comfort even in that, because if such forces working against us exist, then perhaps so do forces of that magnitude that are working FOR us. Plus, there is something utterly freeing in the idea of being without form or limitation in body or mind. Transcendence, I guess, is what draws me most to Cosmic Horror.

In my mind, Lovecraft's views were absolutely repugnant. I cannot understand and do not agree with them. They make me genuinely sad, partly because I feel he willfully missed the opportunity to share creatively with beautiful minds he couldn't recognize, and partly because so many who enjoy his work are conflicted about his views. I have heard that there exists some evidence to show those views were beginning to soften and even changed just before he died, and that in time, he might have recanted them. I have heard childhood traumas and some unusual aspects of his disposition as an adult seem to have clouded what could have been a warm and brilliant mind. I don't know if he would have ever changed, but I reconcile the man with his work by reminding myself that even if he never changed, his fiction legacy certainly has, and will continue to well into the future.

On your podcast, “Cosmic Shenanigans,” you take a look at books, stories, graphic novels, video games, movies, even pieces of art and analyze them through a Cosmic Horror lens. Why did you start this podcast and how has it enhanced your understanding of the subgenre? What do you hope to teach those who listen?

I started the podcast exactly to enhance my understanding of the genre. As I mentioned earlier, I think it's important for those of us writing Cosmic Horror (or any horror fiction in general) to understand the origins and elements of it, to be as well read as possible in the canonical works that sustain it, and to reach others by sharing our passion for and knowledge of it. I have had the opportunity to explore some fantastic works across media that share the aesthetic I love in my own entertainment and my own fiction, and I find I am always discovering new work that reaffirms to me the universal appeal and importance of Cosmic Horror.

What I hope listeners get out of it is a deeper understanding and appreciation of the subgenre. I'd like the mainstream readers and movie-goers and TV streamers to recognize that horror can be as beautiful as it is terrifying, as profound as it is unsettling, and as spiritual as it is visceral; I feel Cosmic Horror is the perfect venue, the perfect horror subgenre, to get that point across.

Finally, we are nearing the 100th anniversary of Lovecraft’s peak years of productivity. Do you think his legacy will continue into another century?

I do. I believe Cosmic Horror is an evolving subgenre that grows in strength and influence with each new writer and each new reader. I think there is something mystical, almost spiritual that draws people to it, something deeply philosophical, something transcendent. I think people will continue to draw from its influence, its standards, and its essence for a long time, and through it, try to better understand the human experience.

Mary SanGiovanni is an award-winning American horror and thriller writer of over a dozen novels, including The Hollower trilogy, Thrall, Chaos, The Kathy Ryan series, and others, as well as numerous novellas, short stories and nonfiction. Her work has been translated internationally. She has a masters degree in Writing Popular Fiction from Seton Hill University, Pittsburgh, and is currently a member of The Authors Guild, The International Thriller Writers, and Penn Writers. She is a cohost on the popular podcast The Horror Show with Brian Keene, and hosts her own podcast on cosmic horror, Cosmic Shenanigans. She has the distinction of being one of the first women to speak about writing at the CIA Headquarters in Langley, VA, and offers talks and workshops on writing around the country. Born and raised in New Jersey, she currently resides in Pennsylvania.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

William Grabowski

Excellent work here, Mary. Outside (pun much intended) these authors and works you mention, one of my early experiences with cosmic horror was T.E.D. Klein's THE CEREMONIES.

Posted : Oct 08, 2020 04:24

Francesco Bruno-Bossio

Very informative and entertaining interview- a lot of content to unpack. I liked Mary SanGiovanni's in depth analysis of the primary feelings of H.P. Lovecraft behind his xenophobia. She's sensitive and insightful. I am not a librarian, but an aspiring author, and yet it was a nice feast for my mind. Glad to see Arthur Machen up here as a recommendation. He's brilliant. But also when it comes to women writers I must impress strongly that Daphne due Maurier is considered well within the bounds for Cosmic Horror for some of her work, especially her short fiction. She was a muse and phenomenon for Alfred Hitchcock.

Posted : Oct 06, 2020 06:35

Nick Mamatas

Thanks for the mention! FYI librarians, MOVE UNDER GROUND (three-word title) was recently reprinted by Dover Publications if you're looking for an edition to add to your shelves.

Posted : Oct 04, 2020 05:45