First Things First

|

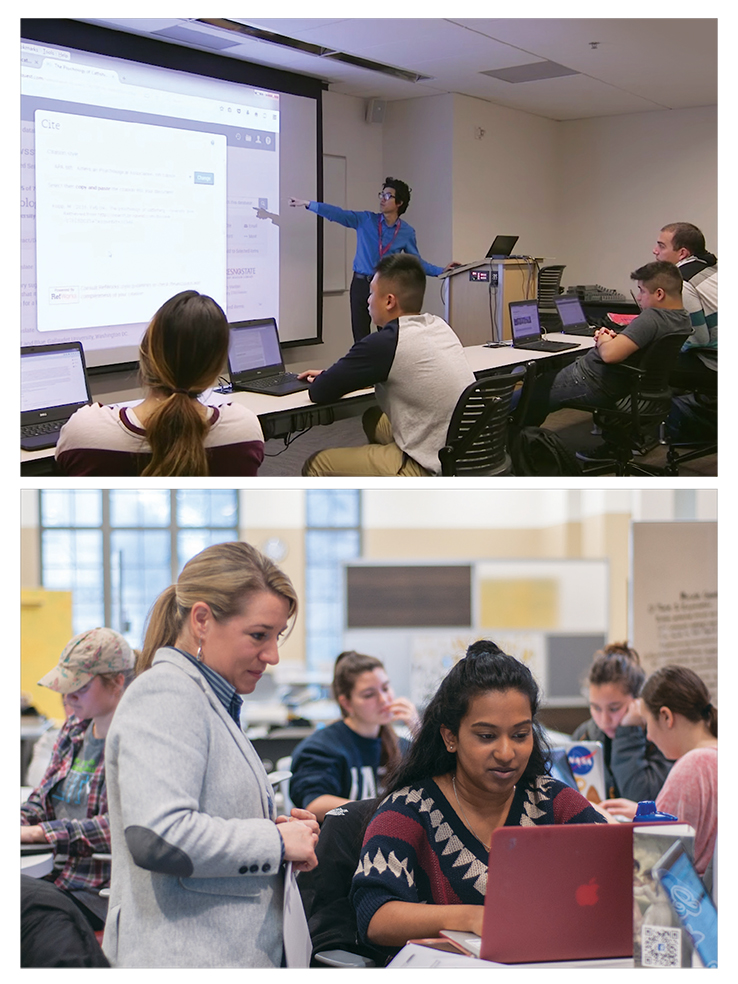

ONE FIRST IMPRESSION (top–bottom): Ray Pun leads a first-year workshop at Fresno State University’s Henry Madden Library; Jen Starkey assists a student at Case Western Reserve UniversityTOP PHOTO COURTESY OF FRESNO STATE UNIVERSITY; BOTTOM PHOTO BY CORINA CHANG, KELVIN SMITH LIBRARY |

Each fall, academic librarians anticipate the arrival of a new freshman class. These first-year students “are quite diverse in their background experiences with research and information literacy,” says Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe, professor/coordinator for information literacy services and instruction at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign. Some have had little or no access to an elementary or high school library. And almost all “are encountering the complexity of a large-scale research library for the first time,” she notes. Several librarians share how they approach reference and information literacy instruction across the spectrum of experience and create relationships that will benefit students throughout their postsecondary education.

PEER-SUPPORTED LEARNING

While some freshmen may arrive at school with basic Google skills, others are more research savvy thanks to high school programs such as the International Baccalaureate (IB) or advanced placement classes. To get a sense of what he was working with, Ray Pun, formerly first-year student success librarian at Fresno State University, CA, and a 2012 LJ Mover & Shaker (M&S), ran a pretest in his first-year research workshop. “This short survey contains a few questions [about] using databases, deciphering citations, and the research processes,” says Pun. Based on the students’ results, “we created a peer-learning exercise in the classroom where students worked in pairs or teams to help each other find resources for their research topics.” He adds, “learning from each other can be an effective way to engage with students and to promote opportunities for students to become peer leaders.” Pun notes that this was an experimental approach and in hindsight he would have added a post-test to see how much participants’ information literacy skills improved.

Disguising an assessment as a class ice-breaker works for Kirsten Hostetler, instruction and outreach librarian at Central Oregon Community College, Bend. By posing a question such as, “What was your last research topic, and did you find it easy to find information?” Hostetler can determine experience and comfort level. “Then I can group the more experienced with the least experienced,” she says. “Our students can be the best teachers because they know the pitfalls they face better than I can. This also makes it more manageable for me to work one-on-one with the students who need extra support.”

Amy Harris Houk, head of research, outreach, and instruction at University of North Carolina, Greensboro (UNCG), also notes the benefits of a peer-based component in research instruction. “As much as students complain about group work in college, a low-stakes, in-class small group activity gives [them] an opportunity to learn from each other, and they seem to enjoy learning through engaging with each other,” she says.

FIRST-YEAR SEMINARS

The UNCG librarians “collaborate very closely with two large services courses taken by the majority of our first-year students, English 101 and Intro to Communication Studies,” says Harris Houk. “[We] teach information literacy skills such as source evaluation, keyword and topic formation, and citation.” In order to tailor instructional content, Harris Houk and her colleagues rely on a pretest. Doing so “is an excellent way to gauge students’ knowledge of and experience with information literacy concepts and assess how to structure a session that will meet most of the students’ needs.”

Hostetler has been focusing on the concept of genre identification with her library credit classes, especially as it pertains to students who are digital natives. “When I was in college, I could conceptualize decontextualized information I found on the Internet, because I had so many experiences using physical sources,” she notes. “Students now face difficulties in identifying a journal article from a newspaper article from an opinion newspaper article from a website…when the access points for all of the above are practically identical links in a list from a Google search result.” Now, Hostetler has “completely updated my class to spend more time identifying source characteristics, evaluating these sources, and determining why certain sources are more useful for certain questions than I do on navigation, search strategies, or keywords.”

At Illinois Wesleyan University, in Bloomington, the campus library “has a strong connection with our first-year seminar, called Gateway,” according to Stephanie Davis-Kahl, scholarly communications librarian and a 2014 LJ M&S. “Each librarian is responsible for reaching out to the Gateway instructors in our liaison areas.” As a result, each librarian meets with students at least once. “Some faculty intentionally design their syllabi so we can connect with students two to three times over the semester,” says Davis-Kahl, “which is great for scaffolding different concepts.”

Wesleyan information literacy librarian Chris Sweet takes the opportunity in these Gateway classes to run a quick assessment. “I try to ask questions or even just a show of hands to gauge where a class stands for a certain skill or concept.” Sweet strives to “allot time for individual work” in class, permitting students who “have some level of mastery of research skills [to] have a productive session and get some work done. I check in with those who are struggling and provide individual guidance.”

In his time at Fresno State, Pun used the embedded librarian model to reach first-year students. A library presence helps them make the connection between new ideas, such as the peer-review process, and thinking critically about their research. “This can be brand-new and daunting to any student,” Pun says. Working closely with first-year writing, communication, and STEM classes, Pun discovered “that faculty appreciate the library integration to their curriculums because it helped enhance the learning environment.” Pun and his embedded colleagues create custom instructional content for first-year courses to demonstrate “the various tools the library can provide.” Fresno State librarians also partner with a variety of student affairs departments such as the tutoring center and Upward Bound. Adds Pun, “These collaborations allow us to create new workshops, outreach programs, and activities to support first-year students learning critical skills including time management, writing, and research skills.”

WORKING WITH HIGH SCHOOLS

Helping first-year college students succeed often means connecting at the high school level to begin building the necessary skill set. Brian Gray, team leader for research services at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, shares that many students say they aren’t taught research skills or exposed to useful resources prior to arriving at college. In order to bridge the gap, CWRU librarians regularly work with local high school classes at the college library. “We introduce how an academic library differs from other libraries and [demonstrate] some key research strategies,” Gray says. The high school teachers he works with encourage their students to consider their college futures and what they may need from an academic library and to ask about these aspects of their education during college visits. “Creating a ‘value statement’ in the context of the student’s view and needs is critical in all our efforts,” Gray notes.

UNCG works with area high schools through the IB program, according to Harris Houk. The IB juniors “visit the library for a day of research when they are working on their extended essays,” she says. UNCG also hosts a Middle College program, which lets enrolled high school students earn college credits; the university library serves as the “de facto media center” for these students. Librarians teach a four-year curriculum to the Middle College, starting with basic library tours and moving into more advanced research and information literacy skills as the students progress.

THE LIBRARIAN IS IN

Jen Starkey, research services librarian at CWRU, recognizes that “students don’t do much of the kind of research in high school that is expected in college.” In order to help first-year students make a successful transition into the world of scholarly information and research, CWRU librarians are assigned to a first-year resident hall as part of the Personal Librarian program. This, says Gray, “exposes students to experts, develops a relationship between a student and librarian (thus reducing fear of asking for help), and introduces the basics of the library through fun events and activities.” According to the library’s website, Personal Librarian services include helping students find their way through the physical building, assisting with research assignments through database instruction and appropriate citation-building, and providing referrals for other campus departments that may offer additional support. This fall the Personal Librarian program is launching a four-week game, comprised of easy challenges that will help students “connect to the university, to the library, and we hope will foster a sense of community in their residential life.”

Another facet of the first-year research and information literacy experience is communicating the value of these skills to teaching staff. “The most important thing we can do to reach students is to develop relationships with faculty,” says Starkey. “If our faculty trust us and share our mission, they will invite us to work with their classes” and “engage librarians in syllabus and assignment design.” Gray notes that relationships with faculty strengthen learning experiences for students. “By using an existing class and projects students already have to complete, [they can] immediately apply the skills we teach.” Harris Houk notes that UNCG librarians “have begun collaborating with our Special Collections and University Archives to train teachers on how to work with their students [to find and use] primary and secondary sources.”

Outside of structured classes, keeping a door open for individual information literacy and research-based appointments is another way to connect with first-year students. “Students have the opportunity for one-on-one information literacy coaching through our reference and subject liaison services,” says Hinchliffe. At CWRU, the library offers voluntary sessions on advanced research skills, specialized searching, technology used in digital scholarship, how to get published, and many others, according to Gray.

Academic librarians can use these tips to form a holistic plan, including assessments, formal and informal learning opportunities, and peer learning. Hinchliffe prefers to emphasize students’ capabilities rather than their deficits. “This includes identifying places where they might stumble in the learning process so that we can create pathways to overcoming those barriers and developing their abilities.”

April Witteveen is a Community Librarian with Deschutes Public Library in Central Oregon.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!