Fall Editors' Picks

Sifting through catalogs and websites, listening to podcasts and Internet chatter, reading blurbs, and more, our staff searched for the big titles of fall.

Promising fall titles, 33 strong

LJ’s review editors love this time of year, when we get to sift through catalogs and author websites, listen to podcasts and Internet chatter, read the blurbs, dive into galleys, attend book conventions, and book-shop till we drop for what we think will be the big titles of fall. Our list this season is as varied as ever, but still some themes emerge. In both the fiction and nonfiction realms, justice is served and survivors are celebrated; communities of all sorts, social equity activists, women entering late middle age, the grieving, Hamilton fans, bakers and chefs, beekeepers, and librarians are well represented, too.

We also have the comfort of the familiar, with a prequel to Anne of Green Gables, a “Lady Sherlock,” Madame Tussaud, Tana French, Rose Levy Beranbaum, Keigo Higashino, and Fred Rogers (see the spotlight on Maxwell King's The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers). The usual sprinkling of first efforts look promising, with three memoirs, Oyinkan Braithwaite’s debut novel, and actress/activist America Ferrara’s bow as editor of a collection of essays exploring identity. Family makes its way into most narratives, whether fiction or non-, blood or chosen relations. Leaf through our varied choices for fall and pick your favorites from the reading tree.—Liz French

Unlocking the Truth

Felicity Faircloth made quite an impression in Sarah MacLean’s Day of the Duchess (LJ 6/15/17) as a would-be candidate to marry the Duke of Haven. Now, in Wicked and the Wallflower (Avon, Jul.; LJ 6/15/18), the opening salvo in MacLean’s new “Bareknuckle Bastards” series, Felicity doesn’t understand why her former ton friends want nothing to do with her. She’s the daughter of a marquess, the sister of an earl, and she has all her own teeth. One person who does show an interest is Devil, who, with his brother Whit, runs the underground activity in Covent Garden and its mean streets. Their story is complex, but who better to get the inside scoop than a charming lockpick? MacLean is so on her game here. Readers will want to figure it all out from the first page, but there are more books (and more lovers) to come.

Sherry Thomas has left her mark on several genres, among them mystery, with her current series featuring Charlotte Holmes as “Lady Sherlock.” The third series title, The Hollow of Fear (Berkley, Oct.), drifts in and out of previously solved cases and notes familiar characters while it moves forward with Charlotte’s latest probe: someone has murdered Lady Ingram and left her body in the icehouse at Stern Hollow. Scotland Yard is looking at Lord Ingram as the most logical culprit. Charlotte’s deductive skills are put to the test to save her childhood friend. As the story concludes, it would appear there are still more crimes to solve. As tasty as the desserts that keep our heroine in double chins.

Elliot Ackerman has a long list of accomplishments, from a National Book Award finalist (Dark at the Crossing) to a White House Fellowship to serving five tours of duty with the marines in Iraq and Afghanistan. The list will get longer with the publication of Waiting for Eden (Knopf, Sept.). Eden Malcolm is likely the most wounded man in the history of warfare as the sole survivor of an IED in Iraq. His story is narrated by a comrade who died in the same explosion who is hanging around, “waiting.” Eden’s wife, Mary, is waiting, too, and has been for three years as he lies in the burn center in San Antonio. Ackerman describes the indescribable without sentiment or pathos, though readers will probably feel both. At a BookExpo breakfast, Ackerman referred to his work as a meditation on the idea of grief, as a transitory state that we move through, but “what if, like Eden, we don’t move on?” A small book (175 pages) with an unforgettable impact. Elliot, thank you for your service.—Bette-Lee Fox

Repeat Business

My picks for fall are new releases from authors I love, women who made my auto-read list the first time I encountered their work, whether on the page or online. The Proposal (Berkley, Sept.), Jasmine Guillory’s follow-up to last year’s smash hit The Wedding Date, promises to be just as charming and steamy as her debut. Carlos helps Nikole escape from a camera crew after she turns down a very public marriage proposal. The handsome doctor provides the perfect opportunity for distraction when the footage goes viral and her social media turns toxic, but could he offer more than a rebound relationship?

Tana French’s “Dublin Murder Squad” series is wildly popular for its behind-the-scenes look at the investigatory process. In the stand-alone The Witch Elm (Viking, Oct.), she focuses instead on the point of view of a crime victim. After Toby is severely beaten in a home invasion, he and his girlfriend Melissa move in with his uncle, Hugo, who has late-stage brain cancer. A skeleton is found inside a tree in Hugo’s backyard, but memory problems from Toby’s injuries complicate the investigation.

Julia Turshen’s first cookbook, Small Victories, is one of my most-used resources, both for the delicious, straightforward recipes and the empowering tips and tricks (it’s no exaggeration to say that her method for lining a pan with parchment paper has changed my baking life). So I was beyond thrilled to learn about her upcoming Now & Again (Chronicle, Sept.), which focuses on leftovers and includes recipes for dishes that generate them as well as no-doubt-ingenious ways to use them up.

The memoir All You Can Ever Know (Catapult, Oct.) is Nicole Chung’s first book, but I’ve been a fan of her writing for a long time—she’s an alum of the beloved, now-shuttered feminist humor site The Toast and writes for numerous high-profile publications. Her book examines her experience as a transracial adoptee and chronicles her search for her biological parents in Korea, which coincided with the birth of her own child.—Stephanie Klose

Out of the Past

Historical novels spanning the ages—from ancient Greece to late 1970s New York City—dominate my fall/winter reading list. Booker Award–winning author Pat Barker, who explored the trauma World War I caused the male psyche in her acclaimed “Regeneration” trilogy, gives voice to the female victims of literature’s most famous conflict in The Silence of the Girls (Doubleday, Sept.). Drawing on Homer’s The Iliad, she retells the story of the final days of the Trojan War from the perspective of Briseis, the captive queen who becomes a pawn between Achilles and Agamemnon. In this brutal world, women are treated as chattel and sex slaves, but Briseis bravely fights to hold onto her humanity. This is a book for the #MeToo movement.

Next stop is 18th-century Paris, as a tiny orphaned girl named Anne Marie Grosholtz and the eccentric physician to whom she is apprenticed climb the city’s social ladder with their wax sculptures. Lavishly illustrated with Marie’s strange and compelling drawings, Edward Carey’s Little (Riverhead, Oct.) is a boldly original reimagining of the life of the woman who would become the legendary Madame Tussaud. Victorian Edinburgh, Scotland, is the setting for The Way of All Flesh (Canongate, Oct.), a debut historical mystery by Ambrose Parry, the pseudonym for best-selling author Christopher Brookmyre and his wife, anesthesiologist Marisa Haetzman. Medical student Will Raven is beginning his apprenticeship with Dr. James Simpson, the real-life physician who pioneered the use of chloroform as an anesthetic, when he meets housemaid Sarah Fisher, who assists Dr. Simpson with his patients but yearns to do more. Immediately wary of each other, the two nevertheless team up to investigate the brutal deaths of several young women. Will and Sarah make an appealing sleuthing duo whom fans of Caleb Carr’s The Alienist will appreciate.

Feeling nostalgic for the gritty Manhattan of four decades ago? Then Tom Barbash’s evocative and absorbing The Dakota Winters (Ecco: HarperCollins, Dec.) is for you. It is 1979, and 23-year-old Anton Winter, recovering from malaria after a stint in the Peace Corps, has returned to his childhood home in the legendary Dakota apartment building, whose tenants include John Lennon and Yoko Ono. He is recruited to help his father resurrect his talk-show career after a nervous breakdown, but Anton soon begins to question his own path. This touching family drama also brilliantly captures the period, with plenty of amusing celebrity walk-ons.

Weaving back and forth between 1980s Rio de Janeiro and 1990s California, The Caregiver (S. &. S., Sept.) is, sadly, Brazilian-born Samuel Park’s swan song; the author died of stomach cancer shortly after finishing this profoundly moving second novel. Ana, a struggling voice-over actress in Rio, and eight-year-old Mara live only for each other until Ana takes a risky job that has devastating consequences for mother and daughter. Years later, Mara has immigrated to Los Angeles, where she works as a caregiver for a woman dying of cancer and begins to confront her tumultuous past.

Twenty-five years after her groundbreaking Reclaiming Ophelia, which examined the lives of adolescent girls, psychologist Mary Pipher addresses the concerns of their older sisters in Women Rowing North: Navigating Life’s Currents and Flourishing as We Age (Bloomsbury USA, Jan. 2019) as they transition into late middle age. This is bound to become the bible of baby boomer women.—Wilda Williams

Future Classics

I've been enjoying a lot of books this season, and, as usual, mine don't have a theme. I'm a podcast addict, and one of my favorites is Pod Save the People, hosted by organizer and activist DeRay Mckesson, known for his activism in Ferguson, MO, and Baltimore. His debut, On the Other Side of Freedom: The Case for Hope (Viking, Sept.), expands upon subjects that are often discussed on his podcast, especially social change, racial injustice, and resistance. In a time when individual rights are under threat, his work is essential for learning how to move forward.

I've been a fan of novelist and writer Kiese Laymon since I first read his contribution to Jesmyn Ward's collection The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks About Race. His latest, Heavy: An American Memoir (Scribner: S. & S., Oct.), is an unforgettable and unputdownable read about being a black man of size in America. Besides touching on how men experience body shame, Laymon also discusses how the lingering effects of sexual violence and covert racism have impacted his life as he follows in his mother's path of becoming an academic. Another memoir I'm anticipating is There Will Be No Miracles Here by Casey Gerald (Riverhead, Oct.). This one was also a pick at LJ's Shout 'n Share panel at BookExpo-and for good reason. Gerald's mesmerizing debut recalls his childhood in Ohio and Texas and not fitting in because of his blackness or his sexuality. I also appreciate his reflections on the evolution of his faith or lack thereof.

The book club-turned-sisterhood of Well-Read Black Girl has inspired me since its launch in 2015. Founder Glory Edim continues her platform with Well-Read Black Girl: Finding Our Stories, Discovering Ourselves (Ballantine, Oct.), which features essays by black women such as Tayari Jones, Rebecca Walker, Gabourey Sidibe, and Morgan Jerkins. I'm counting on reading contributions from writers I'm familiar with and new ones as well. As a fan of Rebecca Traister's All the Single Ladies: Unmarried Women and the Rise of an Independent Nation, I was thrilled to learn about Good and Mad: The Revolutionary Power of Women's Anger (S. & S., Oct.), in which Traister recounts the historical roots of women's collective anger-from suffragists to the present-and how it has informed American cultural history.

My cookbook collection is always growing, and my favorite pick this season is by baking expert Rose Levy Beranbaum, author of The Baking Bible and The Cake Bible. Her latest, Rose's Baking Basics: 100 Essential Recipes, with More than 600 Step-by-Step Photos (Houghton Harcourt, Oct.) is already one of my go-to resources for making cakes, my last baking challenge. All of her recipes are winners, but I'm especially fond of the lemon bundt cake. Naturally, the next step is to bring some cakes in for my colleagues to sample.—Stephanie Sendaula

For the Record

In late 18th-century America, one of the nation’s most celebrated chefs was a man named Hercules, an enslaved African American cook to President George Washington. The story of his extraordinary life, while familiar to scholars and historians of the period, has remained largely unknown to general readers. Five years ago, author Ramin Ganeshram set out to change that, beginning a novel about Hercules’s experiences. Yet before that work was completed, she was asked to write a children’s book on the subject, which presented its own challenges. Published in 2016, this picture book was recalled by publisher Scholastic over criticism of the artwork’s “cheerful” portrayal of life under slavery, specifically of main character Hercules. Despite having raised her own concerns about the illustrations, Ganeshram had no legal rights to alter anything, discovering that in children’s publishing, authors and illustrators rarely interact. In fact, she realized a great sense of relief when the book was pulled from publication.

Despite the controversy, the award-winning journalist, culinary scholar, and historical researcher never lost sight of the man who had long suffused her imagination. As Ganeshram explains in her Guardian essay, “My Book on George Washington Was Banned. Here’s My Side of the Story” (ow.ly/FLc930kLkWs), “Banning A Birthday Cake for George Washington felt, to me, like an erasure. But we cannot stop trying to reveal these histories.”

Now, with The General’s Cook (Arcade: Skyhorse, Nov.), Ganeshram returns with a skillfully observed historical fiction debut that completes the picture of this real-life Herculean personality. She reconstructs Hercules’s fraught journey and eventual escape to freedom on Washington’s 65th birthday in 1797, two years before the president’s death, which, per the terms of his will, marked the release of all the enslaved people in his service, though slavery in America would not be abolished until 1865. According to culinary historians, Hercules was renowned on the Philadelphia food scene of the time, his presence a commanding and powerful force. To convey his experience as authentically as possible, Ganeshram pored over thousands of records and scholarly materials about Washington and the enslaved persons he owned, listening to hundreds of hours of slave narratives and reading documents. Providing much of the groundwork for Hercules’s character were the personal letters of Washington and his secretary Tobias Lear.

At LJ’s 2018 Day of Dialog, I met Ganeshram, who discussed her work at the “Top Historical Fiction” panel (ow.ly/hjWR30kLW6U). As a writer and gatekeeper of history, she emphasized her duty to Hercules and other people of color who triumphed despite untenable injustices. In telling Hercules’s story, she hopes to provide him with some measure of restitution by guaranteeing that his life, and the lives of others like him, are not omitted from the historical record. As depicted by portraitist Gilbert Stuart on the book’s cover, Hercules is dignified and self-assured. Readers will be rewarded in discovering and sharing his story.—Annalisa Pešek

Long Waits

Narrators who are revealed to be murderers and presumed- dead victims who show up in the second act: the bizarre twists of suspense novels have shocked me for years. Now that I’m a little older and a lot more jaded, Japanese author Keigo Higashino is the rare writer who still astonishes me—not with unexpected twists but with elegantly matter-of-fact prose, tightly crafted plots, and intriguing premises. Every year, I hope that another of his books has been translated into English; though he has dozens of novels to his name, most are available only in Japanese. I am being rewarded now with the sinuous Newcomer (Minotaur: St. Martin’s, Oct.). While the work centers on Mineko Mitsui, a middle-aged divorcée who is strangled in the Nihonbashi area of Tokyo, Higashino takes his time getting to her, first wending his way through the neighborhood shopkeepers whose lives briefly intersected with hers.

The result is a complex and moving mystery that’s eventually solved by the astute Detective Kaga, whom fans may remember from Malice. Higashino isn’t the only author for whom I’ve been patient. I’ve wondered about the protagonists of YA author David Levithan’s Every Day (2012), the story of A, a teen with no corporeal form who awakens daily in the body of a different person. One brief but intense afternoon, A falls in love with Rhiannon and spends the rest of the novel reconnecting with her. In 2015, Levithan penned Another Day, told from the perspective of Rhiannon, and, finally, he revisits these characters with Someday (Knopf, Oct.). What could have been a gimmick is a thought-provoking meditation on existence and a love story for the ages. Readers who have been cheering for A and Rhiannon from the beginning will snap up this one.

Though I’ve just become aware of slam poet and short story writer Oyinkan Braithwaite’s literary prowess after reading her debut novel, My Sister, the Serial Killer (Doubleday, Nov.), I realized I’ve been waiting for a book like this for years: a work of suspense that deftly entwines family secrets with the dark undercurrents of beauty and female bonds. Set in Lagos, Nigeria, this terse narrative burns with long-simmering resentment. Korede has stood in the shadow of her vivacious, gorgeous younger sister, who turns heads everywhere she goes—and leaves a trail of murdered men in her wake. Lovely Ayoola claims self-defense each time yet still entreats Korede to help her cover up her crimes. Braithwaite has me hooked; I’m already hoping for her next one.—Mahnaz Dar

Group Efforts

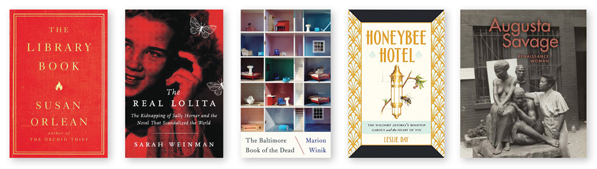

Library communities, true-crime communities, artists and bee colonies, restaurant and community outreach workers, the quick and the dead all jump off the pages of my fall picks. Nonfiction superstar Susan Orlean isn’t a librarian, but she enters that vast clubhouse with The Library Book (S. & S., Oct.), which connects many stories: the devastating 1986 fire that burned for seven-plus hours, destroying Los Angeles’s Central Library; a weird, wonderful history of L.A. and its citizens and librarians; Orlean’s love affair with books and libraries; and the saga of a man whose dreams of stardom were fulfilled when he was the center of attention at an arson trial. Every page is a wonder, and even the most knowledgeable librarian will learn something new.

Another nonfiction star on the rise is Sarah Weinman, who has been on the crime scene as editor and writer, fiction and non. Her breakout title, The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel That Scandalized the World (Ecco: HarperCollins, Sept., see review, LJ 8/18) looks at a little-known true crime that (she argues) influenced one of the most scandalous novels of the 20th century, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. Many early readers have commented along the lines of “you won’t be able to read Lolita in the same way,” and that’s true, but Weinman’s book will also impress readers with its dogged research and empathetic telling.

Empathy figures in Marion Winik’s The Baltimore Book of the Dead (Counterpoint, Oct.), along with her sharp eye and wicked wit. This sequel to The Glen Rock Book of the Dead has more achingly beautiful and succinct obituaries of the people (and a few pets) from Winik’s wide, idiosyncratic circle of family, friends, colleagues, lovers, and enemies. This superfast read will spur rereading and the terrible wish that more people in Winik’s circle would expire just so she could memorialize them. Urban naturalist Leslie Day writes about the flora and fauna of New York City in Honeybee Hotel: The Waldorf Astoria’s Rooftop Garden and the Heart of NYC (Johns Hopkins, Oct.). It tells of how a community formed around a garden and beehives high above Midtown Manhattan. The most uplifting part of the story reflects on how the bounty from this rooftop jewel is shared with a nearby homeless shelter.

Uplifting her community was what Harlem Renaissance sculptor and artist Augusta Savage was all about. Cofounder of the Harlem Artists’ Guild and the first director of the Harlem Community Art Center, she offered free art classes to locals at her studio and went on to influence many artists, including Gwendolyn Knight, Norman Lewis, and Romare Bearden. Art historian Jeffreen Hayes’s Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman (D. Giles, Oct.) is packed with photos of Savage’s work and art by those she influenced, correspondence and period images, and essays by art and African American studies scholars.—Liz French

Personal History

While there’s nothing quite like curling up with L.M. Montgomery’s original series, I can hardly complain about the many Anne of Green Gables adaptations, on page and screen, that have become especially prevalent in the last handful of years. The latest comes from Sarah McCoy, who imagines the farm long before Anne shows up in Marilla of Green Gables (Morrow, Oct.). Fans get to see the formidable Marilla during her younger years while she keeps order for her family, meets her best friend and local gossip Rachel, and considers life in—and beyond—Avonlea. I’m particularly excited to read about her relationship with John Blythe, eventual father to my first and most important literary crush, Gilbert. The courtship is only briefly mentioned by Marilla as a missed chance in Montgomery’s work, but it becomes the crux of McCoy’s and provides more dimension to the woman Anne would come to know and love.

Another lady getting some recognition this fall is Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton (1757–1854), who was raised in an influential New York family; married a Founding Father; birthed eight children; endured a cheating scandal and the death of a child; founded an orphanage that exists today; and secured her slain husband’s legacy. Tilar J. Mazzeo unpacks all of that and more in Eliza Hamilton: The Extraordinary Life and Times of the Wife of Alexander Hamilton (Gallery: S. & S., Sept.). Actors Megan Mullally and Nick Offerman give readers a different kind of history: that of their own romance. The Greatest Love Story Ever Told: An Oral History (Dutton, Oct.) has the couple reminiscing about their 18 years together. And if the blurb is any indication, it will be filled with the humor each is known for in their careers as well as the silliness and joy that they exude as a couple. Relationship goals, indeed. A different kind of personal story comes from actress and activist America Ferrara’s American like Me: Reflections on Life Between Cultures (Gallery: S. & S., Sept.). Ferrara discusses her identity as American and the importance of her Honduran heritage. The book includes 31 other contributors (including author Roxane Gay, Broadway composer/star Lin-Manuel Miranda, and Olympic figure skating medalist Michelle Kwan) discussing growing up with strong connections to more than one culture.—Kate DiGirolomo

Back in the Neighborhood

Maxwell King, CEO of the Pittsburgh Foundation and former editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer, began fundraising for the Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media (FRC) at Saint Vincent College, Latrobe, PA, in 2008. “There I learned about Fred’s extraordinary presence as an innovative educator and an exemplary figure. I proposed to the chancellor of the college that we take on the writing of a biography,” King explains. Nearly a decade later, the fruit of King’s extensive research comes together in The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers (Abrams, Sept.; LJ 8/18). This definitive biography covers this iconic figure’s childhood, education, and career as well as his impact on child development, public television, and American culture....For more, see Kiera Parrott's "Maxwell King Explores the Life and Legacy of Fred Rogers."

Kate DiGirolomo is the former SELF-e Community Coordinator, Bette-Lee Fox is Managing Editor, and Stephanie Klose is Media Editor, LJ. Kiera Parrott is Reviews Director, Mahnaz Dar is Reference and Professional Reading Editor, Liz French is Senior Editor, Annalisa Pešek is Assistant Managing Editor, Stephanie Sendaula is Associate Editor, and Wilda Williams is the former Fiction Editor, LJ Reviews

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!