2018 School Spending Survey Report

Libraries and Book Collections as Essential Cultural Institutions | ALA Annual 2015

While it has always fallen to libraries to preserve the historical record of the communities they serve, libraries also need to consider their own history—especially in light of the changing landscape they face. At the American Library Association (ALA) Annual Conference, a panel of three authors whose recent books focus on private, public, and academic libraries spoke with moderator Barbara Hoffert, editor of LJ’s Prepub Alert, on Libraries and Book Collections as Essential Cultural Institutions: A Historical and Forward-Looking Perspective. The panelists discussed their own studies, and charged libraries to examine the cultural legacies of their own collections.

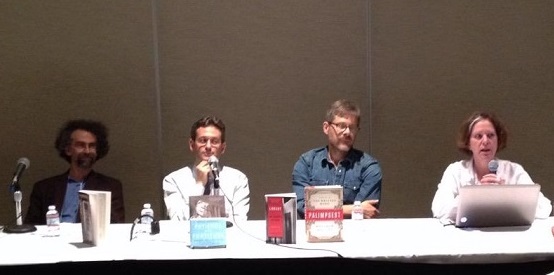

Photo courtesy of Claire Kelley, Melville House

(l. to r.:) Abramsky, Sherman, Battles, Hoffert

PAPER, PARCHMENT, VELLUM

Sasha Abramsky, author of The House of Twenty Thousand Books (New York Review Books, September) led off with a vivid portrait of his grandfather Chimen Abramsky, a historian, bibliophile, and owner of the titular house. The elder Abramsky was a renowned collector of modern Judaica and socialist literature—“modern” referring to anything published in the past 500 years—consisting of books, prints, and manuscripts, related Abramsky. His grandfather eventually amassed an enormous private library that included Karl Marx’s handwritten letters, William Morris woodcuts, and first editions of Spinoza and Descartes. He cared not only about a book’s content, but the details provided by its physical state: the quality of the paper, printing errors, and where different editions were printed all told stories and situated his books in a particular place and time. Abramsky’s grandfather maintained a salon of sorts in his London home; his grandmother “was never happy unless there were 15-20 people in the house and she was feeding them.” Abramsky recalls walking around listening to the conversations and realizing how they were nurtured by the physical texts—his grandfather would answer an argument by reaching up and picking a book off a shelf to read from, so that the placement of the books provided a certain intellectual trajectory. “How do you do this in a digital age?” Abramsky asked the room. If all his grandfather’s books had been on flash drives, he said, there would have been access to the conversation but no way to stimulate it. “The books were the social lubricant—they were what started the conversation.” Yes, he said, digital technology saves work and brings it back to life. “But what I would urge anyone here is: don’t forget all the majesty of paper, or parchment, or vellum.” Books provide a public entry point into a conversation, he said, and he hopes that paper will also be preserved as an important and vital part of written knowledge.A CHANGE OF PLAN

Scott Sherman related the beginnings of what would become his account of the battles over proposed renovations to the New York Public Library (NYPL), Patience and Fortitude: Power, Real Estate, and the Fight to Save a Public Library (Melville House, June). Sherman first uncovered the story in 2011 while working on a profile of NYPL president and CEO Anthony Marx for The Nation. While gathering information, he said, a source told him of the library administration’s plan to sell off three branches, carry out a major renovation of NYPL’s iconic main building—including the removal of its steel stacks—and relocate some three million books to an offsite storage facility. The Central Library Plan, as it was known, began generating controversy shortly after Sherman broke the story. It became the subject of a letter-writing campaign, numerous articles and blog posts, lawsuits, and eventually a public hearing in June 2013. NYPL has been historically cash-starved, Sherman said; by 2007, it had “no more valuable paintings left to sell.” The plan, he explained in Patience and Fortitude, was driven largely by real estate interests and NYPL’s board of trustees, which he described as “the richest, most powerful people in New York.” It was ultimately shelved in 2014 when Mayor Bill de Blasio took office, and is now awaiting a new set of plans with more public input. The mayor, Sherman pointed out, opposed the plan but will not claim responsibility for defeating it, nor has he appointed a City Hall representative to NYPL’s board of trustees.FROM ESOTERIC TO COMMONPLACE

Matthew Battles, associate director of Harvard University’s metaLAB at and a fellow at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society, is the author of Library: An Unquiet History (Norton, 2004) and, most recently, Palimpsest: A History of the Written Word, out from Norton in July. He traces his fascination with libraries, he said, back to his post–grad school days working at Harvard’s Widener Library in 1996. He took a staff job because he thought the library was a good place for a would-be writer; it became his subject as well. One striking thing about Widener’s stacks, Battles noted, was the layers of social and intellectual history in its physical arrangement. The library uses two classification systems: the standard Library of Congress system and the Widener System—now called the Old Widener System, and used for perhaps 20 percent of the library’s books. The Widener System is topical in nature, arranged in “wonderful classes evocative of the state of learning and teaching at the turn of the last century, when Widener was built.” There are individual classifications for proverbs, war, Molière, the Ottoman Empire, Descartes—“Just seeing these archeological strata laid out on shelves told a story of this institution,” said Battles. When Widener began to convert its physical card catalog to digital format, Battles became interested in what he calls “the archeology of the library—what the library had been, meant, done for people in different times and places.” Libraries have played many roles, he explained, from the esoteric to the commonplace; from Widener to a small town Carnegie library; from a protector of knowledge to a place that emancipates or empowers. “The library has never been one thing, yet it’s an incredible institution that’s also an archetype,” said Battles.CATALOGING PSYCHOLOGY

What about the physical act of collecting and cataloging, asked Hoffert, as a way that libraries shape culture? It’s good to remember that libraries don’t have the same meaning for everyone, Battles noted, and that library ethics are historical; they need to be renewed from one generation to the next. He offered as an example a library catalog from the 17th century, in which the classifications corresponded to the two columns of tables in its reading room: one for secular books, and one for sacred volumes. The books were arranged hierarchically from Bible to canon law, from the celestial increasingly closer to earth, with the secular subjects progressing from philosophy through history, geography, and then mathematics—the catalog as a model for the universe. Fast forward, he said, to the 19th century when institutions began collecting everything they could, including all kinds of material that wasn’t intended to produce knowledge but rather document what was already known, such as government documents. In other words, Battles explained, the model of the library changed because our conception of the universe changed. As a historian and a scholar, said Abramsky, his grandfather cataloged everybody else’s collections, evaluating Judaica in libraries worldwide. His own collection, however, was organized by memory. Abramsky believed he was psychologically unable to create his own catalog: “When you leave it chaotic there’s an element of unfinishedness to it—incompleteness, unpredictability, finding something you weren’t expecting to find.” That way, he said, “hopes of the element of randomness can be preserved.” And yet the codex isn’t the only path to uncovering connections, Battles noted. “Digitization can afford and allow discovery in unique ways,” as in the case of a student who wrote code for finding patterns in special collections metadata tags that weren’t initially obvious or visible in the finding aids. The history of the library is our key to the future, said Battles. But, he added, it’s not just about print vs. digital—it’s a richer, more diverse future than the dichotomies currently arising in public discourse would suggest. And, as Abramsky noted, “Paper is technology.” Libraries of the future will tell stories about us to our children, Battles said; “continuing to extend that map and model of the world seems like a mission of the highest order.”RELATED

RECOMMENDED

TECHNOLOGY

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!