2018 School Spending Survey Report

Lazarus Project Brings Damaged Texts Back to Life

Many libraries, archives and museums have in their collections textual artifacts that can no longer be read. Now a multispectral imaging initiative is uncovering value that can’t be detected by the human eye in ways that were previously only available to the largest and most deeply resourced institutions, and without having to take fragile manuscripts off-site.

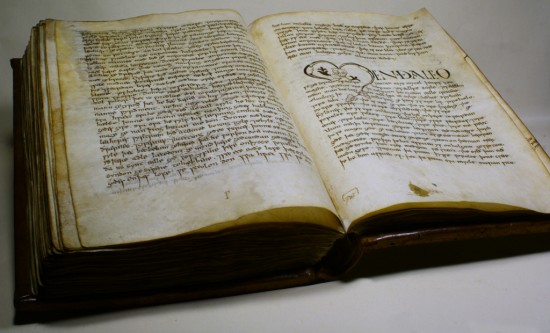

The Vercelli Book, the oldest manuscript of Old English in existence, imaged by the Lazarus Project at Archivio Capitolare in Vercelli, Italy

Many libraries, archives, and museums have in their collections textual artifacts that can no longer be read. Now a multispectral imaging initiative is uncovering value that can’t be detected by the human eye in ways that were previously only available to the largest and most deeply resourced institutions, and without having to take fragile manuscripts offsite. It’s called The Lazarus Project, and it’s designed to give small and medium-sized institutions and individual researchers access to the most cutting-edge digital imaging technology available. The project brings a traveling multispectral lab directly to participating institutions. “We help librarians create value in their own holdings,” said Gregory Heyworth, the project’s director. Ancient and modern manuscripts that are damaged or otherwise illegible are imaged using multispectral imaging—technology that records manuscripts under a controlled spectrum of light. The images are then processed to reveal details that the naked eye cannot see. Instead of exposing fragile materials to large amounts of damaging light, the Lazarus Project's portable rig takes images with light that amounts to merely opening the manuscript. This minimizes damage and comforts conservators who worry about exposing their precious papers to even more harm. The results are often surprising, as when the Lazarus Project team uncovered erased ownership signatures in Shakespeare folios at the Folger Shakespeare Library and what might be William Faulkner’s fingerprints on what may be poems by the author. With the help of the expert team, erased, illegible and damaged text becomes legible material. That’s important, said Heyworth. “Library collections are often forgotten by the scholars who are just next door,” he explained. “Sometimes people just don’t know what exists. Once you know what you have, it’s describable. We help libraries make the most of their collections, especially damaged collections.” The technology can also be used for more than just uncovering ancient erasures—more and more collections are turning to the Lazarus Project to establish a baseline of conservation data for modern objects, Heyworth said. James Kuhn worked with the Lazarus Project during his tenure as the assistant dean for Special Collections and Preservation at the University of Rochester. “Institutions are filled with printed books and manuscripts that often have been obliterated or overlooked,” he said. “There aren’t a lot of opportunities for cultural heritage institutions to do work in this kind of way—we have limited budgets. It can be hard to justify investing five or six figures in multispectral imaging. Those costs are coming down year by year and that’s an argument not to buy it now.” To curators and library professionals, the Lazarus Project’s cost is just as intriguing as the secrets it reveals. For large institutions, it covers its team’s own expenses and helps obtain grants to cover the rest of its expenses. For small institutions, its services are free. That’s made possible in part by the initiative’s other side: annual projects undertaken in connection with Heyworth’s "Image, Text, and Technology" course at the University of Mississippi. To Heyworth, it’s just as important to use today’s most cutting-edge technology to create tomorrow’s digital humanities experts as it is to ferret out the buried and damaged secrets that lie within collections’ caches. He hopes that one day, the Lazarus Project will help fuel a new generation of scholars through a minor or master’s degree in textual science. For now, though, he’s content to take his rig to librarians and archivists who are curious about what their collections really hold. Librarians and archivists who want the Lazarus Project to come to their institution will need a description of an object, its damage, and how multispectral imaging could help. Visit lazarusprojectimaging.com for details.RELATED

RECOMMENDED

TECHNOLOGY

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!