Intersections of Women, Libraries, and Activism | ALA Virtual 2020

This year marks the 100th anniversary of [white] women’s suffrage and the 50th anniversary of the American Library Association’s (ALA) Social Responsibilities Round Table Feminist Task Force (FTF). In honor of both milestones, the ALA Virtual Conference panel “Herstory Through Activism: Women, Libraries, and Activism” offered a compelling look at the intersections of feminist activism in libraries, and how the current era of COVID-19 has changed the panelists’ priorities for urgent change.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of [white] women’s suffrage and the 50th anniversary of the American Library Association’s (ALA) Social Responsibilities Round Table Feminist Task Force (FTF). In honor of both milestones, the ALA Virtual Conference panel “Herstory Through Activism: Women, Libraries, and Activism” offered a compelling look at the intersections of feminist activism in libraries, and how the current era of COVID-19 has changed the panelists’ priorities for urgent change. Moderated by Sherre Harrington, director of Memorial Library at Berry College, GA, the discussion highlighted the intersection of Black identity and womanhood in the profession, adding up to a portrait of both how librarianship has evolved and how far it still needs to go.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of [white] women’s suffrage and the 50th anniversary of the American Library Association’s (ALA) Social Responsibilities Round Table Feminist Task Force (FTF). In honor of both milestones, the ALA Virtual Conference panel “Herstory Through Activism: Women, Libraries, and Activism” offered a compelling look at the intersections of feminist activism in libraries, and how the current era of COVID-19 has changed the panelists’ priorities for urgent change. Moderated by Sherre Harrington, director of Memorial Library at Berry College, GA, the discussion highlighted the intersection of Black identity and womanhood in the profession, adding up to a portrait of both how librarianship has evolved and how far it still needs to go.

FEMINIZED—AND RACIALIZED—SPACES

Emily Drabinski, interim chief librarian at the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate Center, NY, led off with an overview of Libraries as Feminized Spaces, noting that it was interesting to talk about the future of feminized libraries at this moment in time (the panel was recorded in May). Drabinski referenced the FTF’s work to get the Melvil Dewey leadership award renamed in 2019 in light of ALA founder Dewey’s racist, sexist, and anti-Semitic beliefs. That was a significant success, she noted—one that “calls to mind a lot of the contradictions that I think about when I think about libraries and feminist work.”

With her first slide, of mid-century women librarians dressed in skirts and sweaters, Drabinski owned up to dressing in “librarian drag” when she first started out. Librarianship is traditionally a site of female employment and feminine work, she noted, even though leadership has too often been male. A lot of women, she suggested, chose the profession because it was full of women; as a lesbian librarian, she knew she would find a lot of people like herself.

Libraries are also racialized spaces, Drabinski added, and are overwhelmingly white. “It is a white field and it is a feminine field, those two things together,” she said. Libraries are institutions that reproduce social inequalities as well as being produced by them; even with decades of work to diversify the profession and make room for women of color, the numbers still haven’t changed: As of 2018, according to the AFL-CIO Department for Professional Employees, librarianship remains 77 percent white.

So why bother working for change? Because libraries are also sites of struggle, bringing together women—particularly women of color who often work in lower-paid parts of the field. “We can struggle together, to make a better world possible,” Drabinski concluded. As she deals with demands on her library to reopen in the wake of COVID-19 closures, many of the conversations involve frontline workers who are often women of color, while white women continue to stay home and work behind the scenes. “It’s hard to think about, and hard to grapple with, but I think it’s the kind of thing that shows us exactly what libraries could do,” said Drabinski. Libraries could take that problem and, in the process of solving it, work toward equity among different groups: professionals and paraprofessionals; white women and women of color; women, men, and nonbinary people. “If we can struggle through the kinds of divisions and produce that are more equitable, I think we could go a long way toward producing equity in the broader world.”

TWO L.A. LIBRARY ACTIVISTS

Dalena Hunter, librarian/archivist for Los Angeles Communities and Culture at UCLA, continued with a presentation highlighting Black Herstory Through Two Library Activists in Los Angeles: Miriam Matthews (1905–2003) and Mayme Clayton (1923–2006). Both came to L.A. in search of economic opportunity and social freedom, and dedicated their careers to improving preservation of and access to materials involving Black history and culture. “Both women were raised in families that placed a premium on education,” explained Hunter, “and they both regarded their work as part of a larger calling.”

Matthews, who came from a middle-class Black family, was the first trained African American librarian in California, receiving her MLIS in the 1940s. She worked at the Los Angeles Public Library (LAPL) as a branch and then regional manager. “She had resources that allowed her to prioritize certain African American initiatives, not only in the library but also civically,” Hunter explained. Matthews leveraged her position at LAPL and her social status to establish Negro History Week events and to advance Black LAPL’S Black sculpture and art collections. She received multiple awards for her work from the city and the California Library Association, among others.

Clayton, also raised to understand the importance of Black history and education, received her MLS from a correspondence course, and worked as a staff member at the UCLA Law Library. Although as a staff librarian she didn’t have the same resources for collection development as Matthews, she spent her life collecting books, films, posters, and other Black history materials. She eventually established the Western States Black Research and Education Center, which became the Mayme A. Clayton Library and Museum, and donated some of her collection to the UCLA Center for African American Studies when it was founded in 1969. Shortly before she died she rented an inexpensive space in Culver City, CA, to preserve and display her materials and hold events. Much work went into the space, but Clayton died soon after establishing it; her sons took over, but they were unable to keep the institution active. The Clayton Library and Museum is no longer viable, and the collection is in storage.

Matthews used her role at the library and in the city to bring attention to Black history, while Clayton was known to dumpster dive and search yard sales for artifacts. But both were part of a larger movement of Black library workers who documented and preserved African American contributions to culture, operating within Black communities, family, and religious spheres. Their approach differed greatly from that of white women in the profession who did not need to consider the same issues.

“Both used race and gender issues to bring attention to race and equity issues in librarianship and access to information,” said Hunter, and both women’s histories speak to the need for advocacy initiatives, as sometimes even the best of intentions don’t consider the realities of the marginalized communities most in need of attention.

INTERSECTIONAL ACTIVISM

Teresa Y. Neely, professor and assessment librarian at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, presented on The Doubling of Oppressions: Sexism and Racism in LIS. She opened with a quote from African American activist Mary Eliza Church Terrell: “A white woman has only one handicap to overcome—a great one, true, her sex; a colored woman faces two—her sex and her race.”

Neely offered a brief background on 20th- and 21st-century feminist movements, from the first white feminist organizations through the Combahee River Collective, a radical Black feminist organization active from 1974–80, which was formed as an alternative to the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). “The inability or unwillingness of most white feminist organizations to engage with antiracist issues affecting Black women paved the way for organizations like the collective and the NBFO,” she explained. These groups created entry points for Black and brown women to engage in activism and politics.

Kimberlé Crenshaw’s identification of intersectionality in 1989 helped articulate the idea of multiple oppressions that reinforce each other. While “woman and people of color” is a phrase frequently used to designate underrepresented populations, women of color didn’t see themselves in either group, because they belonged to both. Lumping them together removes Black women from the equation, said Neely; that is a violent act, and another way to silence women’s, and Black women’s, voices where they should be amplified. There are interlocking, intersecting systems of oppression that women of color face across the board, and librarianship is part of this. “It is problematic when we can’t even talk about race in our profession without including other non-race related groups in the conversation,” said Neely.

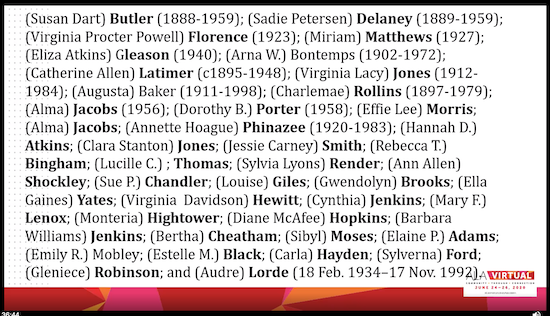

Black women and librarianship have long been allies, said Neely; they have advocated for their communities, colleagues, friends, families, and themselves in a profession that is overwhelmingly white. She offered up an impressive list of women who have blazed trails in challenges of Black librarianship. “Let us not forget the challenges they faced that contributed to changing the profession,” Neely concluded. “There is still much work to be done, but it is intoxicating to be in the company and follow in the footsteps of these amazing women.”

FEMINIST IDENTITY AND URGENT ISSUES

Harrington had final questions for the panelists: Do you consider yourself a “feminist”? Why or why not?; and, What do you see as the most urgent issue(s) for activist librarianship?

After looking at Hunter and Neely’s presentations, Drabinski said, “feminist” feels like a difficult label to take on as a primary identity, because the term fails to grapple with the whiteness attached to it—particularly within librarianship.

Hunter considers herself a feminist, she said, though it’s not the main part of her identity—she identifies first as a Black lesbian woman. But “the term feminism in general is a useful frame and tool, and set of ideals and practices that help me navigate the different spheres that I’m in. It’s something that people understand, and it’s a point of departure.” There’s still a lot of power in the word, she added, so she doesn’t feel comfortable distancing herself from it—rather, we need to strengthen it by making sure the term is inclusive.

Neely didn’t concur. “My whole life and everything about me is Black,” she said. The concept of feminism and the movement were not created for people who look like her—just like higher education, where she works, was not created for people who look like her. “If something is created and it does not have me or everything that is important to me in mind, which for me is being a Black woman,” Neely said, “I don’t feel a connection.”

What are the most urgent issues for activist librarians? Drabinski wondered how that answer would have been different three months ago. In May, as she watched the pandemic murder poor people and people of color, she said, the most urgent issue is large-scale equity outside of libraries. “How can I make the library a site to struggle toward racial and economic equity in my city?” she asked.

“It’s interesting that you mention the pandemic and the people who are most affected by COVID right now being low-income communities of color,” said Hunter. Service industries, including feminized fields such as librarianship, are also part of that. “I think most urgent issue for activist librarianship is to completely pull the rug from under the idea that librarians and libraries are these neutral spaces that can equitably dispense information and materials and services,” she added. Librarians need to acknowledge their part in a system that treats people as privileged based on racial categories, acknowledge those privileges, and move on from there.

“In the midst of this pandemic, Black people are still being murdered by police,” said Neely; that is a primary urgent issue for her, she noted, and “it’s very difficult for me to separate myself as a Black woman from the librarian.” As the only African American at her workplace, “You’d watch it on the news and then you’d have to go to a faculty meeting full of white people who, for them, that’s not even an issue. But that could have been my nephew. It could be my nieces. It could have been my siblings. I see my family in all of those bodies.” Neely wished that her white coworkers could empathize—but that’s not even on their radar, she said.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!