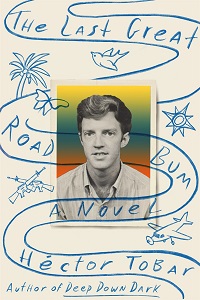

Héctor Tobar’s The Last Great Road Bum: Who Tells the Story

In his third novel, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Héctor Tobar reimagines the adventures of real-life Joe Sanderson, linking the United States and Central America as he considers who can claim the act of storytelling.

After road bumming his way through 70 countries over nearly two decades, Illinois-born Joe Sanderson died fighting with the guerrillas in 1982 El Salvador, a trajectory that calls forth visions of the idealistic  young Americans who joined the Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish civil war. The truth, as revealed through fiction—Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Héctor Tobar’s original and invigorating third novel, The Last Great Road Bum (LJ 8/20; MCD: Farrar)—is more complex. Having deeply researched the real-life Sanderson, Tobar strove for accuracy as well as imaginative reach while creating his Sanderson, both a self-serving adventurer and an exemplar of American can-do big-heartedness, a dreamer and would-be novelist whose story links past and present, America and Central America. What results, finally, is a book about writing itself and who gets to tell stories in today's world.

young Americans who joined the Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish civil war. The truth, as revealed through fiction—Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Héctor Tobar’s original and invigorating third novel, The Last Great Road Bum (LJ 8/20; MCD: Farrar)—is more complex. Having deeply researched the real-life Sanderson, Tobar strove for accuracy as well as imaginative reach while creating his Sanderson, both a self-serving adventurer and an exemplar of American can-do big-heartedness, a dreamer and would-be novelist whose story links past and present, America and Central America. What results, finally, is a book about writing itself and who gets to tell stories in today's world.

Tobar’s venture with Sanderson actually started with a book—Joe’s diary, held by the Museum of the Revolution in El Salvador. While working as the Mexico City bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times, with Central America as part of his brief, Tobar was told about the diary by a fixer in San Salvador named Alex Renderos. “I asked him to send me some pages, and it was a fantastic story,” explained Tobar in a phone interview with LJ. “So I went down to El Salvador and interviewed a bunch of former rebels.” Soon he was hooked by their stories about the crazy gringo who went by the nom de guerre Lucas and was committed to the cause yet insistent on his coffee, cigarettes, and time to write.

Initially, Tobar considered crafting a nonfiction work about Joe, but his book proposals “fell kind of flat.” As he wrapped up two major works— The Barbarian Nurseries and Deep Down Dark: The Untold Stories of 33 Men Buried in a Chilean Mine and the Miracle That Set Them Free—he began thinking about Joe’s aspirations to write the Great American Novel, part of the reason for his inveterate travels. “It seemed to me that Joe had done all these things to go and write a novel. He had tried to live his life like a character in a novel so that he could write a novel and prove to his parents that he wasn’t wasting his time as he traveled the world,” observes Tobar. “And I thought, Why not write a novel about a guy trying to write a novel by living his life like a character in a novel? And that seemed to me like a pretty unique premise.”

As he crafted Joe as a fictional character, Tobar didn’t limit himself to the incongruously tall, blond guerrilla fighter of the El Salvador era but interviewed friends from Joe’s Champaign-Urbana youth; his 100-year-old father, Milt Sanderson; and women Joe somewhat fecklessly loved and left while also plunging into the treasure chest of letters Joe sent home regularly, saved by his brother, Steve. As Tobar explains, “One of the things I learned as a journalist and especially working on the book about the Chilean miners is that you really have to know the complete person for them to come alive on the page.” That wholistic view can’t arrive through diary alone, says Tobar. "Unless you know the person very well, you’re not going to be able to understand a lot of it.”

Joe as Writer

Joe’s absorbingly detailed El Salvador sojourn highlights the bloodiness and moral quandary of war, yet it also emerges as a fitting culmination  of his life. “He was able to fully commit himself to something,” observes Tobar. “He was accepted into the most dramatic struggle, the most beautiful struggle he could have imagined—this guerrilla army formed by teenagers and undergraduates, peasants and armed women.” Ever the helpful Midwestern boy, he leaped in to give instruction in swimming and handling a gun (he was a crack shot), and the medical skills he had picked up during his travels came in handy. Yet his Yankee individualism exasperated some of his compañeros, and his lack of writerly discipline certainly exasperated Tobar.

of his life. “He was able to fully commit himself to something,” observes Tobar. “He was accepted into the most dramatic struggle, the most beautiful struggle he could have imagined—this guerrilla army formed by teenagers and undergraduates, peasants and armed women.” Ever the helpful Midwestern boy, he leaped in to give instruction in swimming and handling a gun (he was a crack shot), and the medical skills he had picked up during his travels came in handy. Yet his Yankee individualism exasperated some of his compañeros, and his lack of writerly discipline certainly exasperated Tobar.

“Joe really loved to read, but he didn’t have enough humility to be a great writer,” offers Tobar, emphasizing the need to humble oneself repeatedly before the immensity of literature as craft. Tobar deals intriguingly with Joe as wayward writer by quoting judiciously from his messily voluminous fiction and correspondence, giving an enriched sense of the man while winding back what was becoming a huge story to manageable proportions. Of his own relentless refocusing through condensing and quoting, particularly as he provided context in the run-up to the crucial El Salvador years, Tobar explains, “I thought the boomers would stay with me for the first half of Joe’s life, but I wanted to keep as many readers as I could.”

Tobar also has Joe talk back to him in sometimes sassy footnotes, which not only served to remind him that he was writing fiction but also helped him bring his leading character into the contemporary world. “It’s a way of me commenting about how much the world has changed,” he elaborates, emphasizing in particular how the women’s movement has transformed our understanding of who gets to tell stories and how. “I have a protagonist who is a relatively privileged middle-class white male traveling the world during the time when people still thought of America as the great savior of the world,” he adds, “[and the footnotes are] my way of dealing with the contradictions of the text.”

Whose Story?

Having ambled into Korea’s demilitarized zone with a girlfriend and hitchhiked with Kerouac-inspired insouciance through Vietnam, the Middle East, and Africa, Joe is deemed “one of the great American adventurers” by Tobar. And he's definitely the end of the road bummer’s line, for no one could do now what he did then; Joe had his wheels greased by a level of American power that no longer pertains, and who thumbs a ride through Afghanistan today? Yet despite the story’s world-ranging appeal, Tobar is sometimes met with confusion (especially in academic settings) when he announces that he’s written a book about a white man. His response deepens the important conversation we’re now having about who tells stories and what stories are told.

“A lot of us as writers of color feel that we’re writing in these narrow channels where everything has to be directly related to our own experiences, and that is incredibly limiting,” insists Tobar, who breaks those bars in his new work especially as he explores Joe’s car-crazed, girl-crazed, hunting-crazed Illinois coming of age. Tobar is proud of his book's Midwestern sections—“I put a lot of heart into writing about [Joe’s mother] Virginia Sanderson and her meals in her Urbana kitchen”—yet he readily acknowledges “that’s not where I am supposed to go according to the rules of American publishing.” Those rules miss the very reason he addressed Joe’s life.

“As a citizen of the United States of America and a lover of United States literature, I felt this book was something I had to write,” he explains; for him, it's not just “a bridge between American and Central American literature but…between ourselves in the United States and the global south.” It also allowed him to place himself in American history and show precisely how that history is defined by the tensions between Joe’s perspective and his own. Even as he creates a realistically complex and sometimes frustrating character—friends and family could be as dismayed by Joe as readers will surely be—Tobar clarifies how our world has shifted.

More broadly, Tobar wants his book to underscore what he sees as the core American values of fairness and generosity, as evident especially in Joe’s El Salvador days as they are in the current outpouring of rage from all sides after George Floyd’s killing. “My entire career is based on the notion that a larger North American readership will be able to see these human truths that I know as a centralamericano and that they’ll be able to feel that and understand it the way I do,” concludes Tobar. “That’s the mission of the novel.” It’s a mission accomplished with unusual verve and a buckle-your-seat-belt road trip for us all.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!