Amid Discord, Niles-Maine District Library Board Compromises on Contentious Budget

On July 21, the Board of Trustees of the Niles-Maine District Library, IL, walked back several items in a contentious FY22 budget proposal. Following a three-hour public comment meeting the night before, community protests, and a complaint filed with the Illinois Labor Relations Board on behalf of library workers’ recently joined union, the board adopted a compromise budget—but some feel the concessions are too little and too late.

|

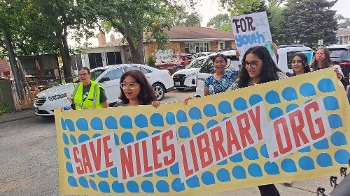

Marchers at the July 20 Save Niles Library rallyPhoto courtesy of EveryLibrary |

On July 21, the Board of Trustees of the Niles-Maine District Library (NMDL), IL, walked back several items in a contentious FY22 budget proposal. Following a three-hour public comment meeting the night before, community protests, and a complaint filed with the Illinois Labor Relations Board on behalf of library workers’ recently joined union, the board adopted a compromise budget—but some feel the concessions are too little and too late.

Since the last board election in April, which created what many have called a “voting block” of four fiscal conservatives out of seven trustees, the board’s cost-cutting agenda has triggered discord among library leadership, staff, and the community, as well as within the board itself.

Less than a week after three new trustees were sworn in, a plan was introduced at a special board meeting that would institute a freeze on spending, hiring, and capital projects; engage a technology consultant to investigate library procedures; hire a new attorney; change board meeting procedures; and raise the staff’s insurance rates. Several weeks later, in a split 4–3 vote, the board approved a tentative $5.9 million spending budget, down nearly 20 percent from last year’s $7.4 million. Also approved in the preliminary budget was a reduction of operating hours, returning to pandemic levels of 54 per week rather the 66 hours the library resumed as restrictions lifted (NMDL was open 70 hours per week pre-pandemic). And on June 18, after a four-hour, closed-door special executive session, former Executive Director Susan Dove Lempke was given the choice to resign with a settlement or be fired; she chose the settlement.

July’s compromise budget eliminated the reductions of staff hours and open hours, but kept cuts to materials, programs, outreach, and capital improvements. In addition, up to $500,000 will be budgeted for attorney and legal fees. Exact dollar amounts were not specified, and will be determined by Business Manager and Assistant Director Greg Pritz before the budget is filed.

NEW BOARD, NEW RULES

Located in Cook County just north of Chicago, NMDL is a single branch library with a service area of 59,000. As a district library, explained Lempke, it is completely under the authority of the board of trustees. “They can do a great deal of damage without many controls on their behavior whatsoever,” she told LJ.

This is not the first time the NMDL board attempted to cut the budget to reduce taxes. In 2013, when Lempke was assistant director, the board reduced the library’s levy by $1 million, and another $200,000 in 2014. Their attempts backfired, however—residents did not care for the cuts, and at election time declined to reelect two of the four trustees who had been in favor of the tightened budget. “They didn’t realize that there were a whole lot of taxpayers out there who valued the library and what the library brought for the community,” said Lempke. The new board restored $800,000 of the levy in 2015.

For several years, Lempke noted, the board and library leadership worked well together. But in the April election, six new candidates ran for three six-year terms and one two-year term. Two of the new candidates—Olivia Hanusiak and Suzanne Schoenfeldt—were elected for the six-year seats, with incumbent Patti Rozanski holding onto the remaining open position; new candidate Joe Makula took the two-year seat. Becky Keane-Adams and Dianne Olson retained their seats, as did Board President Carolyn Drblik—the remaining member of the board that first tried to reduce the library budget. Hanusiak and Schoenfeldt were elected to six-year terms, and Makula to a two-year seat; allegedly Drblik was part of a group that spent $15,000 to campaign for them. Voter turnout was notably low, with fewer than 2,000 people out of 57,000 eligible voters casting a ballot.

Not all the conflict is over money. Prior to the election in April, seven of the eight board candidates took part in an online forum hosted by the library and moderated by Niles Journal reporter Tom Robb (Hanusiak did not attend). When one submitted question asked how the library could better serve the area’s increasingly diverse community, Makula answered, “We should concentrate on people learning English because that’s the language here.” He went on to say, “Instead of stocking up on books in seven different languages, if we got people to assimilate and learn English better, I think we would do more good in that area than increasing our inventory of foreign language books.”

“That set off a lot of anger and shock in the community,” said Elizabeth Lynch, an organizer with the community group #SaveNilesLibrary.

CUTS, CHANGES

The proposed budget was approved on June 16, after several budget workshops that the Journal & Topics described as “contentious.” Several board members reported not having been privy to the mark-up process; the revised budget, with a number of line items written in by hand by Makula, were dropped off at Keane-Adams’s house on the Friday of the Memorial Day weekend. Board members and department heads had only the long weekend to address the proposed changes before workshops—a new process for department heads—began the following Tuesday, she recalled.

“It was like, here’s the thing, and this is what we’re going to vote on. [Nobody asked] how do you think we can cut the budget? Or what areas do you think maybe we could cut the budget? or how much do you think we should cut? It was just like, ‘Here’s what we came up with. Yes or no?’” Drblik, Makula, Hanusiak and Schoenfeldt voted in favor; Keane-Adams, Olson, and Rozanski voted against.

Among other changes, the proposed budget for FY22, which began on July 1, would have reduced personnel hours to reflect shortened open hours, cutting labor costs by nearly $565,000—$150,000 of which represented vacant positions that would not be filled, according to Pritz. Employee copay costs for insurance would increase, and the library would no longer pay professional dues for organizations such as the American Library Association, or travel expenses for conferences. Cutting the library’s operating hours would rule out one of the requirements for a state per capita grant.

Other budget line items slated for removal included visits to schools and classroom materials selection by children’s librarians; outreach assistants delivering materials to the homebound, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities; the overnight cleaning company—library staff is now expected to clean when they are not busy with customers, as well as shelve their own books; the annual staff day; and the annual the Veterans History Breakfast, given for local vets who recorded their memories as part of the Library of Congress’s Veterans History Project. On the hand-revised budget, Lempke reported, Makula “wrote underneath, ‘They can pay for their own breakfast.’”

Half of the library district’s taxpayers live in the village of Niles and half in the unincorporated Maine Township, a 15–20 minute drive away, so eliminating outreach would severely restrict services. The original budget proposed that volunteers deliver materials to homebound patrons—“volunteers that don’t exist at the moment,” Lempke noted. Makula eventually was told that “you couldn't really do that because they didn't want the liability of driving their own cars to people’s houses,” she said, so he withdrew that line item.

In addition to proposed cuts to hours and benefits, the capital project shutdown meant backing out of a major roofing project that the previous board had already contracted for. The new tech consultant, who is allegedly a friend of Drblik’s, according to Lempke, is a wedding videographer with no auditing credentials. “He would have a password to everything you could have a password to, he would have a key to every door and every filing cabinet, he would have 100 percent access,” said Lempke. Although the board agreed to his undergoing a background check, he refused to comply, and later sent results from a different company.

FIRING AND UNIONIZATION

One June 18, after a four-hour, closed-door special executive session meeting, Lempke was offered the chance to resign with a settlement offering extended benefits, among other items; had she not accepted it she would have been fired outright. She chose the settlement. Lempke, an NMDL staff member for 23 years and director for six, has clashed with Makula before. When she declined to certify his 2020 campaign for a referendum shortening trustee term limits to one year—she was advised by the library’s lawyer that she didn’t have the legal standing to do so—he sued her and the library for $25,000 and lost.

So when an eighth board meeting was scheduled as an executive session to discuss personnel, “I was pretty sure at that point that I was about to get fired,” Lempke told LJ. After making a couple of changes, including striking a line that said she could never work at NMLD again—“If somehow [Drblik] was out of there then yes, I would love to go back. I love that library. I love the community. And I really love that staff,” Lempke said—“I took the settlement and said goodbye to the staff who had stayed there till 11 o’clock on a Friday night” to find out the meeting’s outcome and support her. She is currently looking for work in another library.

“They’d been on the board one month and then they wanted to get rid of her,” said Keane-Adams. “That’s just not how things are done in a professional environment. You have some sort of disciplinary action, or some sort of constructive way to work with her.”

At the July 21 meeting, the board voted 6–1 to promote Assistant Director Cyndi Rademacher to the role of executive director, effective immediately.

Even before the proposed budget was approved, the board’s actions propelled a concerned staff into action; in mid-June a majority of NMDL’s nearly 100 employees petitioned the Illinois Labor Relations Board (ILRB) to form a union. The American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Council 31 will represent a bargaining unit of 88 library employees.

On June 21, Drblik and the library were served official notice of unfair labor practices by AFSCME, alleging that proposed budget cuts amounted to illegal retaliation against employees for forming a union. However, with cuts to staff hours now removed from the compromise budget, the complaint will not move forward as long as all outstanding labor issues are resolved. (At press time, the AFSCME union representative had not yet responded to LJ’s request for comment.)

BOARD DISCORD

In addition to opposition from library staff and the community, the NMDL board has showed signs of conflict internally. On June 30, the board held a special meeting to discuss operating hours and public communications policy; 35–40 residents attended in person, with another 90 online.

Two of the items under discussion at the meeting, policies for media inquiries and board president’s communications with library leadership, had not been included in the agenda posted on the library website in advance of the meeting. Drblik “wanted to pass policy saying that nobody but her could talk to the press—not the other trustees, no member of the staff, not the head of PR and marketing, only her,” said Lempke. This was an unusual request, she added; ordinarily communications would fall to the PR/marketing person and the director as well as the board president. The policy did not pass.

Public comments were largely critical of the decision to cut operating hours, also alleging that the proposed changes to the communications policy were designed to impede the flow of information between the library and its stakeholders. The board has not responded to a number of recent Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, many of them from support groups such as the Niles Coalition, a community organization formed to work on issues of race and equity and to advocate for the library. Makula claimed that there was no information available to answer the requests, said Lempke, so he declined to respond altogether. Several residents called for Drblik, Makula, Hanusiak, and Schoenfeldt to resign.

After the public comment period but before the discussion of library business, Keane-Adams, Rozanski, and Olson walked out of the meeting. Hanusiak was absent, leaving only three board members present—one short of a quorum—so the meeting was adjourned.

Several sources LJ spoke with believe that Drblik, Makula, Hanusiak, and Schoenfeldt are anti-tax proponents. “It’s the national story of the fiscal conservatives trying to get seats on local boards, but also it's the story of individual people,” said Lempke. Drblik often took a hands-on approach to the library budget, Lempke said, delaying votes on monthly bill payments and routinely voting no on them. However, she added, “They don't need to raise taxes to keep the budget where it was—that would not have been necessary. Nobody was calling for the levy to be raised.” Drblik has also spoken out against other board members and staff, including through editorials sent to the local paper, according to a source who wished to remain anonymous. (Although Drblik initially responded to LJ’s outreach, at press time, she had not yet provided a comment.)

Board members often do not follow established procedures, several of LJ’s sources said. Lempke noted that, contrary to customary procedure, Drblik casts her vote before the rest of the board. “Normally, the presiding officer of a board would go last, if they voted at all,” Lempke explained, “but she goes first so that her people know how they’re supposed to be voting.” The remaining three trustees—Keane-Adams, Olson, and Rozanski—are consistently outvoted. On one occasion, when Keane-Adams provided a written statement because she would be unable to attend a board meeting, Drblik would not allow the secretary to read it.

“She’s not working with us,” Keane-Adams told LJ. “She’s blocking us from having input.” Schoenfeldt keeps audiotapes of executive sessions at her home, rather than at the library, said Lempke, refusing other board members access to them. Although board members had not been asked for input on whether such records could be removed from the library premises, at the following meeting a policy change allowing it was passed by majority board vote. Makula has held unannounced meetings with staff, which they told Lempke made them uncomfortable, she said.

COMMUNITY RALLIES, BOARD COMPROMISES

As community members became aware of the growing discord between the board and the library, they pushed back with their own grassroots movement: SaveNilesLibrary.org, an offshoot of the Niles Coalition. Congresswoman Jan Schakowsky (D-IL 9th District) and 16 other community leaders signed a letter to the board in support of the library and staff, in opposition to the proposed budget. But unless the board is taken to task by the Illinois Attorney General for violating the Open Meetings Act or refusing to respond to FOIA requests, no effective oversight can be enacted.

More than 150 people attended a rally in nearby Nico Park advance of the public hearing meeting on July 20, which packed the meeting room and overflowed onto the first floor. Library supporters of all ages spoke up at the three-and-a-half–hour meeting to object to the proposed budget—“I loved the many young adults who came out to speak and was thrilled they felt comfortable enough to give their pronouns when introducing themselves,” reported Keane-Adams, “even though there were adults in the front row harassing them for doing so.”

One speaker echoed Keane-Adams’s request to engage a professional parliamentarian, and Niles Mayor George Alpogianis suggested that the board table its vote for a few weeks, offering to help mediate. Keane-Adams, Olson, and Rozanski agreed, but Makula turned down the request, stating that the mayor did not know enough about the budget and that a postponed vote would create “chaos for another two weeks.”

The board’s July 21 compromise budget, brought forward by Hanusiak, satisfied the most critical complaints about reduced hours and staff. However, services and collections will still suffer under the cuts that remain in the plan. “Because they are not filling the current vacancies and not allowing vacancies to be filled for the rest of the year, that will definitely present challenges in keeping the hours and services in place,” noted Lempke.

In addition, no money was set aside for roof replacement or cleaning services, although various line items will be clarified at a later date, and Hanusiak added an amendment that the details of staff hours be worked out by Pritz and Rademacher. The $500,000 for attorney’s fees, said Drblik, would go toward addressing union issues and FOIA requests; she did not consult the board about that item, said Keane-Adams.

Keane-Adams has mixed feelings about the compromise, she told LJ. “I’m glad that the board as a whole was able to collaborate in a small way to the benefit of job safety and service hours. That feels good because we were able to address the needs of two groups, both of which were openly vocal,” she said. But, she added, “I’m still enraged that Joe [Makula] and Carolyn [Drblik] refused to take the mayor's advice and table the budget so that we could revise it.”

While she is not opposed to cutting items in the budget as needed, Keane-Adams finds the lack of willingness to discuss matters discouraging. “We have to be professional and work as a board,” she said. “What we really need to be doing is serving the residents and using their tax dollars, for them, and not for lawyers and consultants.”

“The thing that gets lost in all of the politics is the kids and the seniors and the people that desperately need the library and love it,” said Lempke. “They are in danger of losing something really important to them. And it’s just very sad.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!