UNC Libraries’ Machine Learning Project Analyzes State’s Jim Crow Laws

On the Books: Using Algorithms of Resistance to Expose North Carolina’s Jim Crow Laws is a machine learning and collections as data project of the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill Libraries. Where does the “resistance” come in? Since 2019, the project team has been building an algorithm and searchable database for Jim Crow legislation signed into law in North Carolina between 1866 and 1967 (Reconstruction to Civil Rights era).

|

Civil Rights Demonstrators in Front of the Long Meadow Dairy Store, February 1960, in the Roland Giduz Photographic Collection, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, UNC–Chapel Hill University Libraries |

On the Books: Using Algorithms of Resistance to Expose North Carolina’s Jim Crow Laws is a machine learning and collections as data project of the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill Libraries. Where does the “resistance” come in? Since 2019, the project team has been building an algorithm and searchable database for Jim Crow legislation signed into law in North Carolina between 1866 and 1967 (Reconstruction to Civil Rights era). It is the only project of its kind in the United States at the moment, according to the team, but team members hope that it will not remain that way.

The seeds of the project were sown by a request that UNC Research and Instruction Librarian Sarah Carrier received from a North Carolina high school social studies teacher who was looking for a teaching guide about the Jim Crow era. She was forced to tell him that the only resource that came close to what he was looking for, apart from the bound legislative volumes themselves, was civil rights activist, lawyer, and Episcopal priest Pauli Murray’s States’ Laws on Race and Color (1951). Carrier began looking for a more current way to fulfill the request and approached UNC Data Analysis Librarian Matt Jansen, now co–principal investigator on the project, to ask for his help to help create a text analysis project that would enable them to systematically analyze the legislation.

Since the proposed project aligned with the University Libraries’ Reckoning Initiative, a commitment to using equity, inclusion, and social justice to evaluate and drive all aspects of the libraries’ work, as well as providing a staff development opportunity, the University Libraries took the lead on the project. The project staff expanded and Amanda Henley, head of digital research services, became the project sponsor, assisting in writing the proposal for the Collections as Data: Part to Whole Grant that enabled the team to launch. As part of that launch, the team members had to develop a definition of a Jim Crow law to train the algorithm. They encountered obstacles almost immediately, Henley said: “We were looking for laws that required racial segregation or stratification in any way. The interesting thing is that different experts had different assessments of the laws based on their specific knowledge.”

The team worked with subject matter experts like Dr. William Sturkey of the UNC Department of History and Kimber Thomas, CLIR postdoctoral fellow in data curation for African American collections at the University Libraries, to provide analysis and develop definitions that broke the laws into three classifications: explicit, implicit, or extrinsic. “The explicit laws used clear language that called for or enforced segregation based on race,” Henley said. “Examples include laws that created separate schools, separate cemeteries, etc. Implicit laws contain no clear language about race but are understood to be Jim Crow laws due to their subject matter.” In contrast, an extrinsic law might be defined as a Jim Crow law based on how it was implemented or its outcome.

The laws classified as explicit were the ones that project team members used to train the algorithm. From this initial training period, they were able to identify over 900 Jim Crow laws enacted during the specified time period. These laws were set on the local level as well as the state level and could vary from locality to locality over time. Professor Sturkey pointed out that one of the most useful aspects of this early part of the project was to make it clear how impactful these laws were upon the lives of African American people. He reiterated what he had said in an earlier interview: “These laws were pervasive, inconvenient, and unconstitutional, and they were the result of intricate, detailed planning to build the system of Jim Crow. These laws intended to maintain white supremacy, and they went on for decades and decades.” He also added, “It went well past the water fountains and buses into almost all aspects of their lives.”

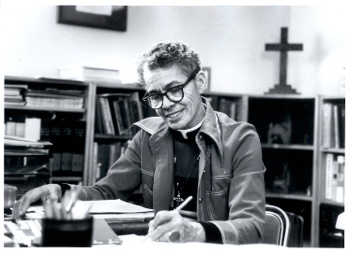

|

Pauli Murray (1910–85), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, UNC–Chapel Hill University Libraries |

Currently, the algorithm is on its second iteration, based on what was learned from the first round of training and testing, and the team agrees that the results are more reliable. Two full text versions (text corpora) of all the laws passed by the North Carolina General Assembly during the specified timeline, as well as the text of the laws classified as explicitly Jim Crow laws, are available on the website so researchers can use them, as well as for spotting any issues and developing additional questions. There is also a section discussing the laws in historical and social context, building on the work and legacy of Murray.

Rebekah Jo Aycock, PhD candidate at the University of Kansas, has been using the database for research on her work on how property crime was racialized and sexualized, and she recommends using the search option for Jim Crow laws, the full text, and the teaching modules in concert to get the most use from the data. “On the Books is an incredible resource for teachers, students, and researchers,” she said, “and it also serves as a great model for anyone doing a similar project focused on a different time period or region. That they take the potential pitfalls of this type of research so seriously strengthens their work immensely and makes me trust it even more.”

Since the project became available to the public roughly nine months ago, the data has been used or accessed some 200 times, by Henley’s estimate. While the team members do not have a precise count of individual users, they have been able to determine that they have had over 8,000 page views from multiple states and countries. In addition, lesson plans developed by Christie Norris, director of Carolina K–12, a program of UNC–Chapel Hill’s Carolina Public Humanities program, are being utilized by North Carolina educators and school programs in growing numbers. As Sarah Carrier put it, “The lesson plans are integral to the overall project. The idea for the project came from a public school teacher in NC, and therefore the practical application and connection to teaching this history and impact have been central.”

All of the project team members hope that this educational component increases awareness and understanding of the impact of Jim Crow laws in contemporary context. Some laws are still on the books while some new legislation has been inspired by some of the original laws. Sturkey noted the impact of these earlier laws on current issues like felon disenfranchisement and voter fraud. In addition, the university is launching a data science initiative to ensure that all graduates are data literate; the project team believes that On the Books makes a strong contribution toward that goal.

On the Books project documentation, learning curriculum, white paper, code, and searchable database can be found here. The project team has secured funding for the rest of 2021 and is working on getting funding for maintaining the project going forward, as well as eventually expanding its scope to other states beyond North Carolina.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!