E.J. Josey: Transformational Leader | Excerpt

During the pinnacle of E.J. Josey’s leadership in the American Library Association (ALA), he fought two systems of institutionalized racism through democratizing librarianship: segregation in the United States and apartheid in South Africa.

This civil rights pioneer led the fight to desegregate libraries and state associations, founded the Black Caucus, and more

This civil rights pioneer led the fight to desegregate libraries and state associations, founded the Black Caucus, and more

This article has been excerpted and edited with permission from E.J. Josey: Transformational Leader of the Modern Library Profession by Renate Chancellor, forthcoming from Rowman & Littlefield this month.

During the pinnacle of E.J. Josey’s leadership in the American Library Association (ALA), he fought two systems of institutionalized racism through democratizing librarianship: segregation in the United States and apartheid in South Africa.

ENDING SEGREGATION IN ASSOCIATIONS

The ALA’s Library Bill of Rights, adopted in 1939, advocated that “[a] person’s right to use a library should not be denied or abridged because of origin, age, background, or views.” Unfortunately, these values were not always practiced by librarians or members of the association. Nonetheless, ALA welcomed Black members and was never segregated.

Segregation became a “real” issue for ALA in 1936, when the annual conference was held for the first time in the South. At the 1936 ALA Annual Meeting in Richmond, VA, Black librarians received invitations from the Richmond Local Arrangements Committee to attend the conference. It was not conveyed, however, that participants would endure segregated conditions. African Americans were not allowed access to conference halls or meetings held in dining areas in conjunction with meals. Black members of the Association were given reserved seating in a designated area of the meeting hall, limiting their participation. Due to protests by delegates and state associations, the executive board appointed a committee to formulate policy to ensure that this discrimination would not occur again. As a result, signs were posted at future meetings “[t]hat in all rooms and halls assigned to the Association for use in connection with its conference, or otherwise under its control, all members shall be admitted upon terms of full equity.”

|

HOPE THEN AND NOW E.J. Josey biographer Renate Chancellor contemplates his legacy from the Capitol steps in Washington, DC, in the same spot that Josey spoke from years earlier (inset). Photo ©2020 Stephen Gosling; inset photo courtesy of ALA |

African American librarians also faced discrimination that denied them membership in southern library associations. Virginia Lacy Jones, former Dean of the School of Library Service, Atlanta University, and Josey were both rejected by the Georgia Library Association. It is likely that this rejection provided impetus for him taking on the Association in the decades ahead. It was not until 1965, after Josey protested the southern state library associations, that he was allowed membership, becoming the first African American librarian in the Georgia Library Association.

JOSEY'S HISTORIC RESOLUTION

The ALA Annual Conference held in St. Louis, MO, in July 1964, coincided with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, outlawing segregation. Josey accepted the invitation to appear on the ACRL College Library Section’s program, on which few Blacks were invited to participate.

At the conference, Josey attended the National Library Week Program. During the program, ALA passed a motion honoring the Mississippi Library Association for its National Library Week activities, in spite of its failure to comply with ALA policies on equal membership to all librarians. The Mississippi Library Association had withdrawn from the ALA rather than permit membership to Blacks.

As [Josey] describes it, “I exploded.” Josey openly opposed the award, saying: “Firstly, Mississippi has withdrawn from ALA affiliation. Secondly, no state association should enjoy the benefits of membership, and at the same time, repudiate the ideals and bylaws of the American Library Association.”

His resolution was rejected. Josey introduced a more comprehensive resolution: “All ALA officers and ALA staff members should refrain from attending in their official capacity or at the expense of ALA the meetings of state associations which are unable to meet fully the requirements of chapter status in ALA.”

Eric Moon (then editor of Library Journal) seconded the motion, and, as Josey describes it, “all hell broke loose.” Months after the motion passed, Josey was accepted as a member of the Georgia State Library Association. Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi opened their membership to Black librarians.

Subsequently, Josey demanded immediate action to eliminate discrimination against African American librarians and other librarians of color in southern public libraries.

DESEGREGATING LIBRARIES

In addition to fighting for civil rights in the profession itself, Josey was integral to the fight to bring an end to state-supported segregation in all public places—including libraries. African American librarians participated in sit-ins in libraries throughout the South. These events not only influenced the national mood, but also motivated library professionals to fight for equality in their profession. National civil rights leader Martin Luther King particularly inspired Josey.

As a librarian at the Savannah State College Library, Josey championed eradicating segregation on campus as well at the Savannah Public Library. He, along with other members of the NAACP, demanded that the mayor of Georgia appoint Blacks to the Savannah Public Library Board. He was one of the first African Americans appointed to the board.

In 1960, Moon published an article, “Segregated Libraries,” by Rice Estes, then librarian of the Pratt Institute, who challenged segregation in the South and questioned whether the ALA was doing all it could for Black librarians. Moon followed with an editorial titled “The Silent Subject” that suggested that Library Services Act funds be withheld from those libraries whose services were not equally available to everyone. That same year the Association approved a survey that documented the lack of access by citizens to library services and emphasized restrictions based on race in the South.

|

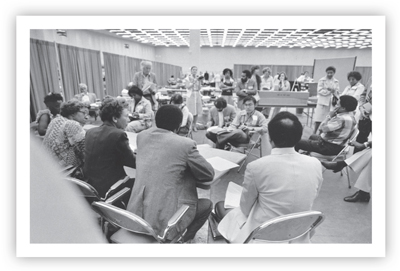

GATHERINGS A Black Caucus meeting at the 1977 Annual Conference in Detroit on their reaction to the showing the film, The Speaker. At the table (l.-r.): Marva Deloach, Ernestine Washington, Avery William, George Grant, and Josey. Photo ©The American Library Association |

SPEAKING OUT ON THE SPEAKER

Josey was involved in several other controversial issues in the Association. One concern that divided ALA was the film The Speaker, produced in 1977 by ALA’s Intellectual Freedom Committee. Intended to “explain the special role of the library in preserving and disseminating controversial works,” the final product was “based on the widely reported confrontation at Harvard University where there was vigorous opposition to presenting William Shockley as a speaker because of his expressed position on White supremacy/Black inferiority.” In The Speaker, this situation was transferred to a high school setting and focused on a speaker who believed in the mental inferiority of African Americans.

Confronting the issue of racism and free speech resulted in an enormous controversy. To the astonishment of the ALA board members, who had approved the making of the film in pre-production, many librarians were upset with the final result. African American librarians became infuriated and boycotted the release of the film. Others objected, countering that banning the movie would be a form of censorship.

Although Josey was not then a member of ALA Council, he often consulted with Clara Stanton Jones, the first African American president of ALA, who held the office at the time. According to Sanford Berman, retired head cataloger and principal librarian at the Hennepin County Library in Minnesota, “[b]oth Josey and Clara Stanton Jones were very vocal about their objections to the film, The Speaker. Josey led members of the BCALA to oppose it....”

Similarly, Josey took issue with negative terminology in Library Cataloging Subject Headings (LCSH). The challenge was led by library activist Sanford Berman who, in 1971, created a list that included approximately 225 sexist and racist headings that required correction. Their goal was to replace terms like “Negro” and “Afro American.”

THE BLACK CAUCUS OF ALA

A popular approach used to combat discrimination in professional organizations was the formation of caucuses. African American librarians formed the Black Caucus of the American Library Association (BCALA), which allowed them to work within the framework of the parent organization to fight against the injustice they experienced at work and in ALA.

Although BCALA was officially established in the 1970s, the momentum for the collaboration began in the 1930s and 1940s when a small number of African American librarians who attended ALA conferences would assemble in hotel suites to commiserate about the injustices they experienced.

At the suggestion of Effie Lee Morris, Black librarians met at the 1968 Annual Conference to discuss their concerns about not having a voice in ALA. It was decided that there was a need for a formal organization. In 1969, Black librarians would also come together “[w]hen the School of Library Service of Atlanta University began to sponsor alumni dinners.” Most African American librarians attended regardless of whether they were graduates of the school.

It was not until two years later that the group came together as a governing body. Josey was uniquely positioned to lead a delegation of Black librarians to form a caucus. A small group of Black and White librarians, who met at the Midwinter Meetings, agreed to establish BCALA. Josey was elected as the first chairman of BCALA, and a statement was delivered in 1970 announcing the establishment of the Black Caucus. Considered by many as the moral conscience of ALA, the caucus members were invigorated by changing times, and were now capable of influencing the larger community.

Josey was also a member of the ALA presidential nominating committee. In this role he wanted to find qualified Black candidates and socially responsible White contenders to run for Council. He sent letters inviting all African American librarians to attend the 1970 Midwinter meeting to discuss potential candidates. During the meeting, Josey not only asked for their support for potential Council representatives, but convinced the group that it was time to elect a Black president. They agreed to support notable African American librarian A.P. Marshall for president.

The effectiveness of the caucus was almost immediately tested. Virginia Lacy Jones, Dean of the School of Library Service, Atlanta University, introduced a resolution against supporting primary and secondary schools created to avoid the 1954 Supreme Court decision [banning school segregation]. The declaration stated: “Be it resolved that the libraries and/or librarians who do in fact, through either services or materials, support any such racist institutions be censured by the American Library Association.” The bone of contention was the continued lending of materials to and support of these institutions. Although the ALA Council eventually passed the resolution, it was not without much debate.

Josey was also a mentor and supporter of other minorities and encouraged them to start organizations targeted to their needs. REFORMA, the National Association to Promote Library and Information Services to Latinos and the Spanish-speaking, was founded in 1971. In subsequent years, the Chinese American Librarians Association (1973), the American Indian Library Association (1979), and the Asian/Pacific Librarians Association (1980) were established. Josey mentored Sal Guerena, director of the California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives, Department of Special Collections, Donald C. Davidson Library at the University of California Santa Barbara, and a member of REFORMA; Guerena [said] “I sought support and advice for my own initiatives and those of REFORMA. While serving on ALA Council I knew I could count on E.J.’s support and he would speak up forcefully at the microphone whenever I needed another voice for some measure being voted on by Council.”

|

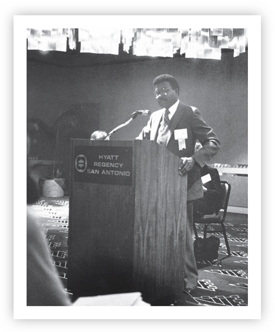

ACTION-ORIENTED Josey speaking at ALA, circa 1970. Photo ©The American Library Association |

TAKING THE LEAD

A movement to elect [Josey] as the first male African American president began in the 1980s. Josey was nominated to ALA Council as Vice-President/President Elect in 1983.

When Josey prepared to take on his new leadership role as the 101st President of ALA, many publicly funded institutions, including libraries, suffered from cutbacks. Accordingly, Josey chose Forging Coalitions for the Common Good as his presidential theme. Individuals had begun to buy into the notion that private sector information services could replace services offered by public institutions without expense to the taxpayer. Josey wanted to dispel this belief by reaffirming the concept of the public good and developing coalitions with other organizations to promote public sector support of libraries.

He articulated his vision in his inaugural address on June 27, 1984, in Dallas, TX: “The public good, in an even broader sense of the general welfare, is closely related to progress for libraries. In a time of attack on the basic freedoms and economic well-being of the most vulnerable sections of populations, professional groups must recognize their stake in the outcome of that attack and their responsibilities to support the freedoms and welfare of these people. Librarians therefore need to integrate their goals with the goals of greatest importance of the American people, e.g., the preservation of basic democratic liberties, the enlargement of equal opportunity for women and minorities, and the continuance of earlier national planning to raise the level of the educational and economic well-being of greater numbers of the population.”

His vision of fairness was further carried out by establishing an ALA Committee on Pay Equity as well as a presidential committee on library services to minorities, now known as the Committee on Minority Concerns and Cultural Diversity. The findings from a 1984 report, “Equity at Issue,” indicated that there was an under-representation of librarians of color in professional positions [a problem which persists to this day]. The committee was charged with providing a forum to research, monitor, discuss, and address national diversity issues and trends and the relevance and effectiveness of library leadership and services to an increasingly diverse society; and to provide Council and ALA membership with information for the establishment of ALA policies, actions, and initiatives related to national diversity issues and trends.

Patricia Glass Schuman, former President of the ALA and longtime friend of Josey, contends that, during Josey’s presidency, “he literally changed the color of the Association’s committees through his appointments.”

Sal Guerena also praised Josey for his commitment to librarians of color: “His major Equity at Issue initiative was a broad-based strategy that was all-inclusive and aimed to create systemic change throughout the ALA organization to create positive change within ALA and achieve greater equity to meet the needs of people of color.”

PIONEERING INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

Recognizing early on that international relations were not a priority for ALA, Josey advocated for the exchange of books and other materials from overseas and Africa. He first became involved with the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) in 1974 when its meeting was held in Washington, DC. It was the first time that IFLA had met in North America since World War II. Josey had a strong interest in librarians from African countries and firmly believed that international relations could be improved through international librarianship. Josey became an advocate of international librarianship and urged the ALA to work collaboratively to improve international information transfer. In 1977, when Moon was president of ALA, he appointed Josey as Chair of the ALA International Relations Committee (IRC). The Association had not developed a formal policy on international relations until Josey chaired the committee. He also encouraged member library publishers and others to donate materials to libraries in developing countries.

Arguably, the highlight of Josey’s term as president was the joint meeting of BCALA and the Kenya Library Association for a weeklong seminar prior to the IFLA Conference in Nairobi, Kenya. Approximately 30 librarians engaged in discussion of issues of mutual concern: building ethnic collections and resources; challenges with publishing and acquiring African and African American materials; and information technology. George Grant, Dean of Library and Information Resources at the Dean B. Ellis Library at Arkansas State University, a friend of Josey for over four decades, and an active member of the BCALA, remembers that “participants left with a sense of accomplishment and a vow to combat racism at all levels of librarianship.”

As a spokesman against discrimination, it was no surprise when Josey led a campaign against apartheid in South Africa. At the IFLA General Conference held in Chicago in August 1985, Josey vehemently protested against the South African delegation. The impetus for his objection was an excerpt published in the South African newspaper, Cape Argus, which reported that large numbers of South African public libraries remained closed to Blacks. At the conclusion of the opening session, Josey “rose to protest the participation of the twelve South African delegates.”

|

VISIONARY Josey speaking at the 1983 Midwinter Meeting in San Antonio. Photo ©The American Library Association |

Josey and his supporters advocated that IFLA exclude South African apartheid associations and institutions as members. At the next IFLA council meeting, ALA Council member Norman Horrocks requested a report on IFLA’s inquiry into apartheid in South African libraries. Secretary General Margreet Wijnstroom presented a resolution that was signed by members from Nigeria, Kenya, Senegal, France, Denmark, England, and the U.S. that read: “South African institutions that adhere to apartheid policies will continue to be denied the privilege of membership in IFLA.”

The resolution passed unanimously [but] very little was done to implement it. Al Kagan, Professor of Library Administration and African Studies Bibliographer Emeritus at the University of Illinois Library at Urbana-Champaign, and a member of IFLA, recalls the frustration with the conflict with the IFLA Council: “Every year at IFLA, we would put together an international delegation of course led by E.J., we made an appointment with the IFLA president to ask for the status of implementing that resolution, and every year the IFLA president would say that they were doing another study, another survey, another something, and they hadn’t done anything with the resolution besides study the problem.”

The reluctance of IFLA’s Council to act led Josey and his supporters to hold a demonstration outside of the IFLA meeting in Stockholm, Sweden in 1990. They joined forces with the local anti-apartheid solidarity movement and, much to the chagrin of the IFLA officers, passed out flyers, made signs and banners, and stood outside the IFLA conference center protesting the Council’s refusal to enforce the resolution.

That same year at the ALA Conference in Chicago, the Association’s position on South Africa was the foremost concern. As the Chair of the IRC, Josey “held hearings to determine whether ALA should endorse the American Association of Publishers (AAP) Report.”

The report entitled “The Starvation of Young Black Minds: The Effects of Book Boycotts in South Africa,” written by notable African American librarians Robert Wedgeworth and Lisa Drew, “proposed lifting the boycott on books.”

However, many of the members of the ALA did not want to lift the ban. Josey fervently supported the ban because he believed the great majority of the South African population would never have access to the books under apartheid.

AN ENDURING LEGACY

Long after his tenure as ALA president in 1984-85, Josey’s impact continued. Starting in 1992, the BCALA began to organize its own national conferences on a biennial basis, as well as meeting during the ALA conference. Josey was very much involved with the early conferences. Because of his important role in founding the BCALA and his contribution to the organization, two scholarships are awarded in Josey’s name annually to African American students enrolled in an ALA accredited LIS program.

Even after he retired in 1995, he would continue to remain an influential actor on civil rights through speaking engagements and publications.

Renate Chancellor is Associate Professor in the Department of Library and Information Science at the Catholic University of America. She received her Master’s and Ph.D. in Information Studies from UCLA. She is a recipient of the Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE) Leadership Award in 2012 and Excellence in Teaching Award in 2014.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!