Digital Humanities Project Visualizes the Impact of Family Separations

A team made up of digital humanities librarians and other academic partners has developed an interactive website that visualizes the impact of Trump administration’s family separation policy’s enforcement and the emerging humanitarian crisis it has engendered.

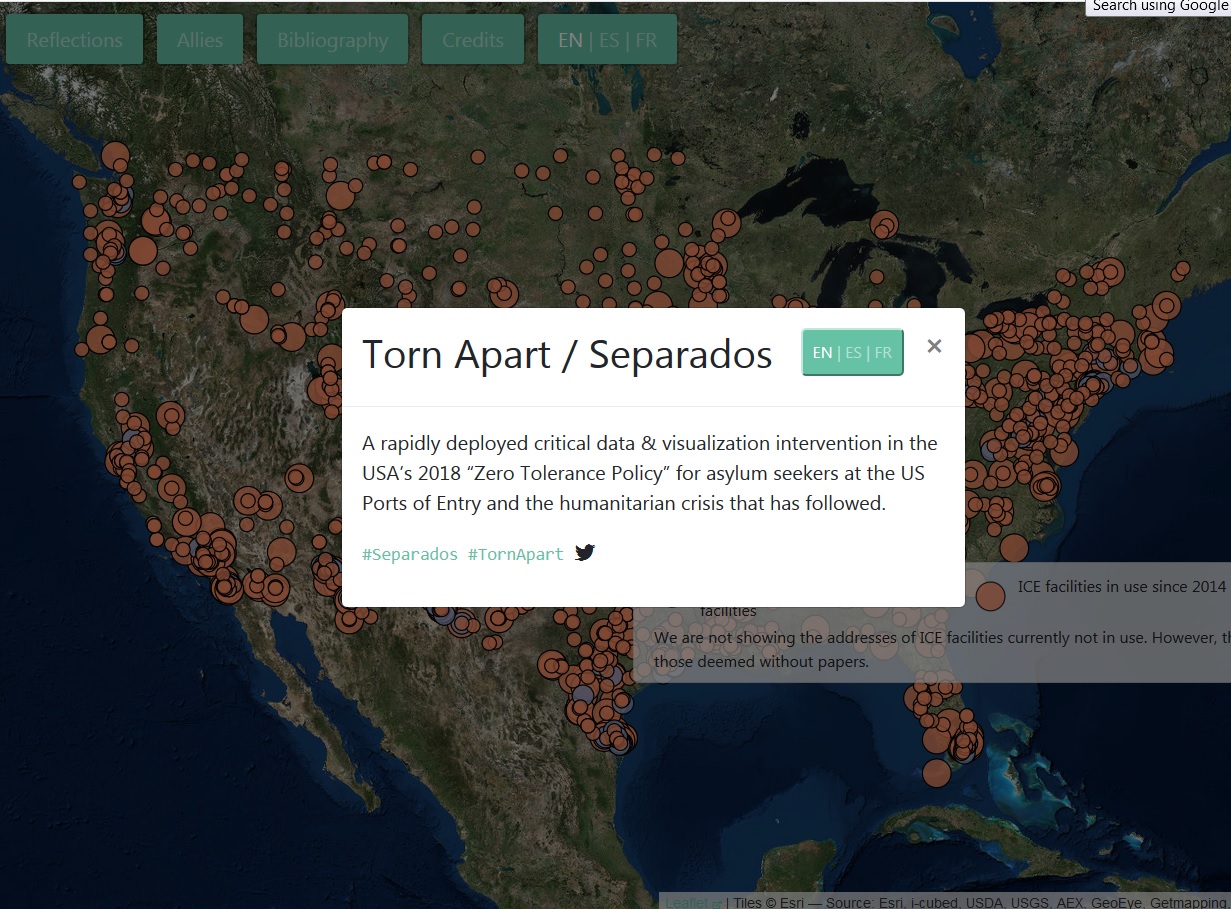

A team made up of digital humanities librarians and other academic partners has developed an interactive website that visualizes the impact of Trump administration’s family separation policy’s enforcement and the emerging humanitarian crisis it has engendered. Torn Apart/Separados is a “rapidly deployed critical data & visualization intervention” combining geographic information system (GIS) visualizations with narrative, essays, links, and a bibliography to unpack data underlying the juvenile detention facilities contracted by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The original site took six days from conception to its launch on June 25; a second iteration is currently in the works.

Under the family separation policy, implemented in April as part of Attorney General Jeff Sessions’s “zero tolerance” immigration policy, adults seeking asylum to the United States were detained at United States–Mexico border crossings and the children they accompanied were placed under the supervision of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The policy was suspended on June 20 and then halted on June 26 by a federal district court injunction, but not before thousands of children had been separated from parents, relatives, or other adults who accompanied them. The administration gave the number as “fewer than 3,000,” although the Department of Homeland Security confirmed that an additional 1,700 children had been separated from families in an earlier pilot program.

As of July 26, HHS reported that 1,820 children had been reunited with their relatives. Another 711 were deemed ineligible for reunification by the government because their parents have already been deported, declined to be reunified or have criminal histories. Numbers aside, however, much of the damage to these children is incalculable—for those reunited after separation as well as the youngsters remaining in detention centers.

On the site’s homepage, juvenile detention centers are shown densely distributed throughout the United States. The initial impulse behind Torn Apart/Separados, explained cofounder Alex Gil, digital scholarship librarian at Columbia University Libraries, NY, "was for America to wake up and stop seeing ICE as this isolated phenomena that happens at the border or Miami, LA, or New York, and start seeing ICE as a national phenomenon…. It's right in front of you. You might not see it, but it's there."

DIGITAL HUMANITIES’ CRISIS INTERVENTION

The project was set in motion after a conversation between Gil and his colleague Manan Ahmed, associate professor for South Asia in Columbia’s Department of History. It was Father’s Day, and they were discussing how powerless they felt about the children separated from their families.

“I was saying to Manan, you know we should…at least do something related to what we know how to do,” Gil told LJ.

The two have used their digital humanities expertise to step up in times of crisis before. In October 2017 Gil and Ahmed organized a mapathon at Columbia’s Butler Library in response to the Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team’s call for crowdsourced mapping services to help relief efforts in hurricane-devastated Puerto Rico. This led to the development of the Nimble Tents Toolkit, an open source set of templates, instructions, and materials to help academic institutions, libraries, and digital scholarship labs mobilize around causes. They are also moderators of Columbia’s cross-institutional Group for Experimental Methods in the Humanities (xpMethod).

Ahmed and Gil saw their colleagues having similar conversations on social media, and decided to put together a team to dig into the issue. Gil reached out to people whom he knew would be committed to the cause, and who could contribute to such a project. Within a few hours they had assembled a group of collaborators that included fellow xpMethod members Moacir P. de Sá Pereira of New York University’s (NYU) Department of English and Roopika Risam, assistant professor of English at Salem State University, MA; Borderland Archives Cartography founders Maira E. Álvarez and Sylvia A. Fernández, respectively research assistant for the Center for Mexican American Studies and PhD candidate in Hispanic Studies at the University of Houston; Linda Rodriguez, visiting scholar at NYU’s Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies; and Merisa Martinez, a PhD candidate at the Swedish School of Library and Information Science at the University of Borås, a visiting research fellow at the Cambridge University Digital Library, and a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Research Fellow in the Digital Scholarly Editions Innovative Training Network (DiXiT ITN).

The team began its research with data sources from publicly available resources such as local news reports, government records, and Facebook, chatting via the messaging platform Telegram and consolidating information in a Google spreadsheet. "We used organizational models that are borrowed from Black Lives Matter, Occupy, and other groups where there's no hierarchy,” explained Gil. Decisions were made by the group as a whole, with no one individual or institution taking the lead. Halfway through the week, they began designing the website as well.

DATA + NARRATIVE

The group had at first planned to explore earlier reports of 1,500 “missing” children, but these turned out to have arrived at the border unaccompanied rather than being separated from their families as a result of the administration’s policies, so it was decided not to pursue that line of inquiry. But from that initial investigation, Risam told LJ, “We learned a lot about how the government manages children when they are taken into custody, particularly around the intricacies of custody between ICE and the refugee resettlement at [HHS].”

The National Immigrant Justice Center provided an extensive set of ICE’s immigration detention data obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request that included information on types of contracts, demographics, medical care providers, and inspections history for more than 1,000 federal facilities that detain immigrants, including county jails, Bureau of Prisons facilities, Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) centers, hospitals, and hotels.

Using data from public records, the group mapped the general locations of shelters where children are housed without providing actual coordinates, this in order to protect the children from protesters or others who might disrupt their lives.

“I was primarily trying to find the locations of the shelters that the [ORR] subcontracts to house children when they're in their custody,” said Risam. “They're pretty closed-mouthed about where these locations are. So we started looking for them.” She focused on finding nonprofit organizations given awards or grants by ORR, old lists of detainee transfer reports, government records, the Federal Register, websites, and media reports—and many of the places she was looking for turned out to be in available telephone listings. The Washington Post also offered data it had compiled.

One of the site’s narrative sections, Textures, examines the project group’s research process, pulling out several strands of pertinent information. “As we cross-referenced our findings among these sources, we found ourselves down rabbit holes revealing the more human and heartbreaking dimensions of immigrant detention,” it reads. These include an examination of detention centers’ management culture—whitewashed or deleted annual reports and notations of booming “job creation” in the detention sector—as well as pleas from parents who have turned to the comments sections of detention center listings looking for information about their children.

The qualitative side of the site was critical to its mission, Gil told LJ. "Data visualization by itself never works. It's always a little bit inhuman, and also hides what the research process looks like,” he said. “Textures allowed us to fill in some of those holes and gaps, correct misperceptions, or at least orient them. It was an opportunity for us to also flesh out a little bit in prose what people were looking at."

The Reflections page supplements the data as well, offering a range of essays from project contributors that range from research to personal recollection. And an extensive list of Allies offers contact information for refugee and immigrant justice organizations and resources throughout Mexico and the United States.

VOLUME 2

Work on the second version of Torn Apart/Separados began as soon as the first was released. In the process of researching the site “we were looking at audiovisual materials and other kinds of documents that were truly heartbreaking,” said Gil. “Most families are still separated. We still live with that pain, and we're continuing the project for that reason.”

Collaborators organized a couple of hackathons during the 2018 Digital Humanities Conference, held June 26–29 in Mexico City, where they formed interdisciplinary teams with separate areas of focus.

“Part of the beauty of digital humanities is that…the skills are mixed,” noted Gil. “One of the things that we're going to try to argue...is this idea that librarians working together with researchers can do amazing things in 2018 and in the future.”

Volume 2, which is scheduled to launch in early August, will explore the financial world of ICE and the impacts of its increased investments in immigration enforcement, family separations, and incarcerations. "We have a number of different ways we're slicing up that data to see what kinds of stories there are to tell about the money,” said Risam. Feedback on Vol. 1 from volunteer peer reviewers was also incorporated.

The new iteration will include visualizations of ICE contracts from 2014–18 that demonstrate the growth of the agency’s economic activity, including awards and expenditures. "It gives this really interesting picture of all of the minutiae that goes around the enterprise of ICE,” Roopika told LJ. “For example, there's a category in the data which has some really specific and kind of horrifying details, like 'detainees need socks.' When we were trying to categorize the services into more general categories...I felt like I was writing a mall directory. Apparel, office supplies, and then—munitions.”

Vol. 2 will also look at ICE spending by congressional district, map deportations since 2012, and provide a thoroughly verified map of allies “to make it more useful to people, so people can find places—immigrant lawyers, social workers, etc., that are close to them,” Gil explained.

Much of the information was pulled from a large data set from USAspending.gov, with more than 100 columns and 2,000 rows of contracts. Risam has done much of the data wrangling for the project. “I was trying to be the person who understood what was actually going on there and how the government documents data around contracting, which is really confusing,” she explained.

“ALL HANDS ON DECK”

Libraries and digital humanities labs have an opportunity to supplement the role of the press, Gil told LJ. “We can be part of the fourth estate in this day and age, with our skills overlapping those of journalism. At the same time we have some freedoms that they don't have.”

“We didn't have any obligation to appear to be neutral or objective, or fair and balanced,” agreed Risam. “I think our politics were quite obvious. Our critique of the infrastructure of detention and of ICE is very clear, and that's something I think gets communicated in the project.”

Gil plans to work with the Digital Library Federation to expand the Nimble Tents Toolkit as well, to provide other activist groups with good documentation, best practices, and tools people can use—as well as strong examples to help convince their administrators that this work is something that their institutions should support. "I think the library community is eager to have more models and more directions so that they can get involved in these types of… projects that respond to a national need,” he said.

“Data Refuge is such a great example—endangered data but also these kinds of research projects that actually leverage some of the things we're really good at, which is identifying data sources and filtering them out. And on the digital humanities side of the house, being able to represent them as visual or interactive narratives of different kinds…. We're working on projects that can have a positive impact on the world. It's like a natural fit."

In the current political climate, he added, “We need all hands on deck.”

___________________

Editors' note: Alex Gil's position was incorrectly given as "digital scholarship coordinator in the Humanities and History Division of Columbia University Libraries." It has been corrected to reflect his current role.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!