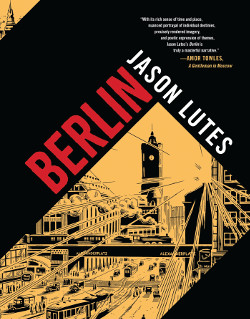

LJ Talks to Cartoonist Jason Lutes About the Highly Anticipated Berlin

More than two decades in the making, Jason Lutes’s Berlin presents a carefully researched masterpiece tracking the final days of the Weimar Republic. Here the author answers a few of our questions about his work and influences.

More than two decades in the making, Jason Lutes’s Berlin (LJ 11/1/18) presents a carefully researched masterpiece tracking the final days of the Weimar Republic. Lutes lives in Vermont, where he teaches at the Center for Cartoon Studies and answered a few of our questions about his work and influences.

More than two decades in the making, Jason Lutes’s Berlin (LJ 11/1/18) presents a carefully researched masterpiece tracking the final days of the Weimar Republic. Lutes lives in Vermont, where he teaches at the Center for Cartoon Studies and answered a few of our questions about his work and influences.

Historical record provides a framework for Berlin’s narrative, but did the direction the story takes change from what you originally conceived when you began it in the early 1990s? Did changes in our culture dictate any revisions to the narrative?

JL: After several years of research, I decided on two main characters: Marthe Müller, an art student, and Kurt Severing, a journalist. After setting them in motion on the stage of the city, my approach was simply to follow them as they went about their lives. Certain historical events would occur at specific points in the narrative, but everything between those points was improvised according to the needs of the characters. Inevitably, but in mostly unconscious ways, my real-world experiences played into and affected the fictional world I was creating. For half of the 22 years it took me to write and draw Berlin, I was living in Seattle, and I felt a resonance between those two cities that subtly infiltrates the story. Just before leaving Seattle, my wife and I had our first child, and my hopes for her future are in some way embodied by the character of Silvia Braun, a working-class orphan.

Throughout the novel, there’s a palpable sense of interconnectedness among the characters and the city itself. At one point, Marthe says she feels like she’s everyone and doesn’t exist at all. Did you deliberately set out to explore this make-or-break relationship between a place and its people or did this evolve on its own as the story developed? What do you hope readers who have never set foot in a major city might take away from the story?

It evolved on its own, according to how I imagined Marthe would handle the situation in which she found herself. During the Weimar period, as gender norms were challenged or tossed out, the possibilities for women in German society suddenly exploded. But without clear precedent or passionate internal drive, that possibility could turn into paralysis for someone in Marthe’s position. Not unlike the newly minted Republic itself, which sought to fill the void left by a monarchy.

Human settlements are born and grow organically in proximity to essential resources like potable water or arable land. At a certain size, they become gathering places for like-minded people—LGBTQ folks, artists, or mathematicians, for example—who might be isolated or marginalized in their respective hometowns. Subcultures gathered in proximity generate friction, competition, and the exchange of ideas, which together lead to advances across all fields of human endeavor. This might be exciting or intimidating, depending on your personality. In any case, it’s fascinating to observe.

Was it difficult or daunting to find ways to create a feeling of empathy and express the humanity in a cast of characters divided across such extreme economic and political lines?

Was it difficult or daunting to find ways to create a feeling of empathy and express the humanity in a cast of characters divided across such extreme economic and political lines?

Certainly challenging, but I never felt daunted by it. In each case I would imagine the character as fully as possible, building up from a foundation of background research and then imagining how they feel and what they’d do in a given scene or situation. I grew up playing (and I still play) role-playing games [RPGs], so from an early age I was pretending I was someone else, shifting roles as the story demanded. I’ve never trained as an actor, but the process of inhabiting a part is somewhat similar to how I approach writing individual characters.

The transformation of Berlin from a burgeoning, inclusive society to a place of tyranny as the Nazis rise to power is especially chilling. How did these parallels of past and present influence your storytelling?

The hippie in me believes that we’re all potentially connected at a profound level and that we can feel connection if we take the time and care to listen. We can respond to that possibility in different ways, anywhere on the spectrum between violent denial and trusting acceptance. I listened very carefully while I wrote and drew Berlin, keeping my mind open as my characters made choices on a stage built by history. Sometimes I think it’s crazy that such unconscious decision-making led me down a trail that runs parallel to real-world events in ways my conscious mind could never have predicted. And sometimes I think I just did what anybody could do if they took the time: reached down to feel the vibration on the railroad tracks.

How does your experience with RPGs influence you as a storyteller?

I really can’t overstate the influence of Dungeons & Dragons, which I discovered in 1977 at the age of ten. In the midst of absorbing stories from books and movies and television, I happened upon this form of entertainment that not only put the storytelling in my hands but turned it into a game I could play with my friends. Tabletop RPGs are collaborative by nature, so whatever story emerges from play doesn’t belong to a single author. This communal experience taught me to look outside myself for inspiration, to empathize (with the other players and our fictional characters), to run with ideas without second-guessing, and to hold the reins loosely.

Your first book, Jar of Fools, concerns itself with a group of magicians, and in Berlin you have David, an obsessive fan of Harry Houdini. What draws you to magicians?

The demonstration of the apparently impossible can evoke a feeling of wonder in the most jaded adult, and I find that really interesting. Saying that now, I’m reminded that this feeling of potential or possibility—anything can happen, the future is unwritten—runs through all of my work, and I strive to keep it alive in my own life.

As far as Houdini specifically is concerned, I’ve always been affected by the fact that he was a Jew who could escape any literal bonds placed upon him and in so doing illustrated the potential (there’s that word again) for a greater metaphorical freedom.

If you could send one message back in time to yourself as you began this project, what would it be?

“Trust the vibration. You’re on the right track.”—Tom Batten & Annalisa Pešek

Tom Batten is a writer and teacher whose work has appeared in the Guardian and The New Yorker. He lives in Virginia. Annalisa Pešek is Assistant Managing Editor, LJ Reviews

This article was originally published in Library Journal's November 1, 2018, issue.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!