Library of Congress Launches Crowdsourcing Platform

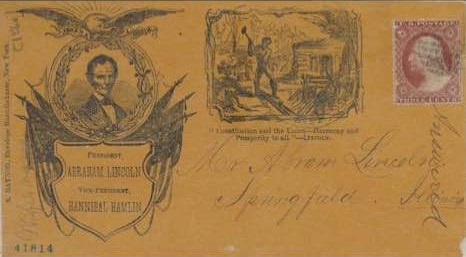

The Library of Congress (LC) last month launched crowd.loc.gov, a new crowdsourcing platform that will improve discovery and access to the Library’s digital collections with the help of volunteer transcription and tagging. The project kicked off with the “Letters to Lincoln Challenge,” a campaign encouraging volunteers to transcribe 10,000 digitized versions of documents written by or to Abraham Lincoln, which will make these materials full-text searchable for the first time.

The Library of Congress (LC) last month launched crowd.loc.gov, a new crowdsourcing platform that will improve discovery and access to the Library’s digital collections with the help of volunteer transcription and tagging. The project kicked off with the “Letters to Lincoln Challenge,” a campaign encouraging volunteers to transcribe 10,000 digitized versions of documents written by or to Abraham Lincoln, which will make these materials full-text searchable for the first time.

On November 19, LC hosted a one-day special event in support of the new initiative, celebrating the 155th anniversary of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address with a transcribe-a-thon, livestreamed remarks from Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden and LOC historian Michelle Krowl, and a viewing of the Gettysburg Address.

The new project is the earliest example of LC’s new Digital Strategy, which complements the library’s new 2019–23 strategic plan. Announced in October, the strategic plan, “Enriching the User Experience,” outlines four high-level goals—expanding access, enhancing services, optimizing resources, and measuring results—while the digital strategy outlines how LC plans to accomplish these goals with its digital resources, described as “throwing open the treasure chest, connecting, and investing in our future.”

“We’ve spent the past year thinking about how we can shift the focus of the Library of Congress to become more user centered,” LC Director of Digital Strategy Kate Zwaard told LJ. “The Digital Strategy…is our vision for what we would like the Library of Congress to look like, in terms of technology, in the next three to five years.”

LC aims to use crowdsourcing to enrich the user experience in two key ways, Zwaard said.

“First, it helps with the legibility of our collections,” she explained. “The Library of Congress is home to so many historic treasures, but the handwriting can be hard to read…. For example, we have this amazing letter from Abraham Lincoln to his first fiancée. It’s really quite lovely, but at a glance, if you’re not familiar with historic handwriting, it’s hard to read.”

Transcriptions are machine readable, making the text of these manuscripts usable in a variety of applications. When displayed alongside these often difficult-to-read digitized manuscripts, the transcriptions will encourage a broader audience of users to explore these collections and make these documents accessible for blind or visually impaired users who require screen reader technology, Zwaard said.

Second, crowdsourcing “invites people into the collections,” she added. “The library is very optimized around answering specific research questions. One of the things we’re thinking about is how to serve users who don’t have a specific research question—who just want to see all of the cool stuff. We have so much cool stuff! But it can be hard for people to find purchase when they are just browsing and don’t have anything specific in mind. One of the ways we can [showcase interesting content] is by offering them a window into the collections by asking for their help.”

Second, crowdsourcing “invites people into the collections,” she added. “The library is very optimized around answering specific research questions. One of the things we’re thinking about is how to serve users who don’t have a specific research question—who just want to see all of the cool stuff. We have so much cool stuff! But it can be hard for people to find purchase when they are just browsing and don’t have anything specific in mind. One of the ways we can [showcase interesting content] is by offering them a window into the collections by asking for their help.”

Other projects currently featured by crowd.loc.gov include the diaries of Red Cross founder Clara Barton, the papers of civil rights activist Mary Church Terrell, baseball scouting reports written by Branch Rickey, and memoirs of Civil War veterans with disabilities. The library plans to continue adding new material to the platform, including “documents from the Rosa Parks papers, the woman’s suffrage movement, Civil War veterans, American poets, and the history of psychiatry,” according to an announcement.

To facilitate ongoing engagement with these varied projects, LC has set up an online forum on History Hub, a site hosted by the National Archives, to encourage crowd.loc.gov participants to ask questions, discuss projects, and meet other volunteers. “It helps us create a community of people who are interested in these materials—scholars, hobbyists, students—we’re hoping that this will help everyone know that the Library of Congress is for them,” Zwaard said.

REFINED MODEL

Crowd.loc.gov is not LC’s first crowdsourcing project. Followers of the library’s official Flickr account have added tens of thousands of descriptive tags to digitized historical photos since the account debuted in 2007. And last year, the debut of labs.loc.gov—which aims to encourage creative use of LOC’s digital collections—included the Beyond Words crowdsourcing project developed by LC software developer Tong Wang.

Zwaard said that the library’s experience with prior crowdsourcing projects informed the development of crowd.loc.gov. She described “Beyond Words,” which asked volunteers for help identifying pictures in LC’s Chronicling America digitized newspaper collection, as a proof of concept project to see how crowdsourcing at scale might work at LC.

“The Library has had a number of crowdsourcing projects, but they’ve all been very ‘handcrafted,’” she said. The most successful one has been the Flickr project…. But the way we incorporate contributions from the crowd on Flickr is mediated through a staff member…. It’s very rich information, but it’s also very time intensive per contribution. With Beyond Words we wanted to see what it would look like at the Library of Congress if we did something at a larger scale.”

One key finding from Beyond Words is that the crowdsourcing model used by the project to determine consensus was not a good fit for humanities projects. When a volunteer transcribes a photo caption for Beyond Words, for example, the program waits for a second volunteer to generate a transcription that matches the first one perfectly. Only then does the program authenticate the accuracy of the transcription.

“This works very well for scientific data and other sorts of structured information,” Zwaard said. “But in humanities materials, you might have someone who transcribes and puts two spaces after each sentence [invalidated by] someone who transcribes and puts one space between the period and the next sentence. Or an em dash versus an en dash would fail [a transcription] in Beyond Words.”

So, crowd.loc.gov was designed to have transcriptions authenticated when a second volunteer reviews the work for accuracy.

In addition to the Gettysburg Address event, the #LettersToLincoln hashtag on social media, and the community forum on History Hub, LC has been getting the word out about the new platform through schools and other organizations.

“We’re partnering with local schools and teachers…interested in using this in their classrooms. And we’re interested in engaging with other populations that might have more expertise in handwriting. We’re looking to talk to groups of retirees and other organizations that might be interested in giving back,” Zwaard said.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!