Four Asian American Narrators Take the Mic

Meet Vikas Adam, Priya Ayyar, Ewan Chung, and Greta Jung—Asian American narrators at various stages of their performance careers, from hundreds of credits (Adam) to not yet quite a dozen (Chung). Each is proof that authentic representation truly matters—linguistic credibility, cultural awareness, and nuanced accuracy—as they embody titles from around the world to create the best possible literary experience for discerning, eager listeners.

The publishing industry has been hard hit by COVID-19: festival and conference cancelations, library and bookstore shutterings, disappearing book tours, publishers’ office closings, production delays—especially with international printers—and, alas, probably more obstacles to come. But digital audiobooks can be the ideal, germless answer to patrons’ long-distance literary needs.

Audiobooks are booming. According to the Audio Publishers Association’s latest survey, sales since 2017 have risen at an impressive rate hovering around 25 percent annually. The latest full year data shows almost $1 billion spent on audiobooks. Such increased demand comes with amplifying awareness for improved representation; as the pioneering hashtag-turned-major-influencer We Need Diverse Books continues to significantly affect the diversification of the children’s publishing industry, and People of Color in Publishing similarly affects diversification across the general book publishing industry, so, too, are audiobook makers and shakers prioritizing authentic representation.

Although the audio industry hasn’t yet founded a WNDB-esque entity of its own, the frequency of diverse titles being matched with similarly diverse narrators is noticeably improving.

Reading on the page and being read to are often vastly different experiences. Even the most resonating, stupendously written titles can become impossible to finish with problematic narration; in contrast, mediocre titles can become unstoppable amusement when helmed by an accomplished performer or skilled cast. Readers who choose to go aural have grown to a critical mass to demand—and get—#OwnVoices representation.

In celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Library Journal asked four Asian American narrators to talk about industry developments, producer expectations, preparation and processes, and their careers.

Meet Vikas Adam, Priya Ayyar, Ewan Chung, and Greta Jung—Asian American narrators at various stages of their performance careers, from hundreds of credits (Adam) to not yet quite a dozen (Chung). Each is proof that authentic representation truly matters—linguistic credibility, cultural awareness, and nuanced accuracy—as they embody titles from around the world to create the best possible literary experience for discerning,

eager listeners.

|

RECOMMENDED LISTENSAdiga, Aravind. Amnesty. S. & S. Audio. 2020. Brierley, Saroo with Larry Buttrose. Lion. Blackstone. 2015. Martel, Yann. Life of Pi. Brilliance Audio. 2018. Roy, Anuradha. All the Lives We Never Lived. S. & S. Audio. 2018. Suri, Manil. The City of Devi. Blackstone. 2013. |

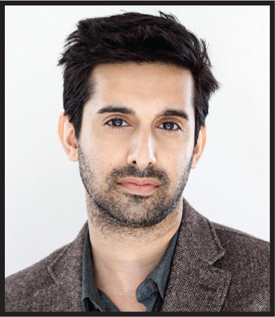

VIKAS ADAM

VIKAS ADAM

The veteran narrator among this foursome with almost 300 audiobook credits, Adam is also an actor, director, writer, and lecturer in UCLA’s Theater, Film & Television department.

How do you choose your projects?

I’m very fortunate that I get to tell stories—I mean, making a living using what I went to school for—it’s a dream come true. Nowadays when I choose titles, I keep numerous factors in mind. How well can I connect with it? Is there an interest in the piece for me? Am I learning something or being challenged somehow?

How did you get into narrating? What do you love most? What do you like least?

I attended a workshop that Audible was having, auditioned, and two weeks later had my first book. I love telling stories and finding ways to interpret them. It’s always fun to play all of the characters, especially in a dialog-heavy scene. What I like least is the isolation aspect. I’m a collaborator and people person, so when I home-record, that lack of human contact can be challenging.

Your ethnic background is Indian/Canadian South Asian American. Unlike TV and film, in which visual first impressions are more important than they should be, in the audiobook world, are you as likely to be cast for non-ethnic-specific roles?

My South Asian background, and specifically my ability to speak with an authentic Indian accent, was a gateway into this business. When I first began, all I received were books dealing with South Asian subject matter. I was grateful, as I was new and it was paying the bills. As work begat work, producers and publishers began to consider me for other books that didn’t specifically deal with South Asian subject matter. And as someone who’s always enjoyed changing things up, I consider myself very lucky to be someone who genre hops.

A very special book for me is The Far Pavilions—it follows the journey of a white British man who was raised as an Indian and is torn between two worlds in colonial India. There are many characters who are brown, white, and in between. It was made into a miniseries for HBO in the early 1980s with a primarily white cast in brownface. You had an anglicized interpretation of Indian words and phrases, and this coming from the mouth of the character who is for all intents and purposes an Indian! So to be able to portray this character and his story through an Indian lens felt powerful and right. Authors and producers want a strong storyteller. So as long as I continue working respectfully and truthfully, I feel that my 23andMe profile won’t be an Achilles heel.

How do you “give life” to your books?

It changes with the book. They each have their own energies. Some of them only need a quick look over, some require a lot more time and notetaking and thinking. Because I have limited time with each piece, I ask a lot of questions both to myself and the author, if possible. My background is in acting, so I do my own version of deconstructing. How does the writing style lend itself to the way the story is told? What is the “movement” of the words, the story? What is the tone? If I get to speak to the author, I’ll ask about characters, trying to get in their heads, trying to understand what drives them. In the end though, my job is to treat every book I work on as if it’s a precious piece of art.

Photo by Mikel Healey

|

RECOMMENDED LISTENSAzar, Shokoofeh. The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree. Dreamscape. 2020. Bajpai, Nandini. A Match Made in Mehendi. Hachette Audio. 2019. Bhuvaneswar, Chaya. White Dancing Elephants: Stories. Blackstone. 2018. Faruqi, Sonia. Project Animal Farm. Blackstone. 2015. Munaweera, Nayomi. Island of a Thousand Mirrors. Blackstone. 2014. |

PRIYA AYYAR

Priya Ayyar narrates the books she didn’t have when she was growing up, books that resonate with her experiences as a California-born Indian American. In the last couple years alone, the chimerical actress has become the go-to voice of young South Asian American and Arab American protagonists.

You and Vikas Adam work on a lot of projects together. How did that come about?

Vik and I are great friends and it was he who first asked me to audition to be a narrator back in 2012. That book, City of Devi by Manil Suri, was our first joint venture and there have been a few others since!

How do you and the producers ensure a sense of continuity in multi-voiced/full-cast recordings?

In far too many titles, a character becomes unrecognizable after POV shifts when represented by different readers. In my experience with multi-voiced/full-cast recordings, the readers have all been separate. It’s important to have a good director who is hopefully from the same cultural background as the author/book. I say this because the last couple books I have recorded on Islam with Arabic and Urdu words have had directors with no connection to the material, no understanding of the culture or heritage or how these words are pronounced, never mind the slight but notable differences in regional accents and dialects. A Pakistani Muslim, for example, has a markedly different accent than a Muslim in Yemen or Syria.

You’ve done a broad range of titles—a Pakistani tween during Partition, a Persian teen facing post-9/11 bullying at school, a middle grade Little Women reboot set in Atlanta, to name just a few! How do you prepare for roles that have such specific, nuanced demands?

A cursory glance at some of the roles I’ve played might look very similar to the untrained eye or ear, but there are subtleties and culturally specific nuances that are very necessary to the biography of the character. Most of the roles I read are in Standard American but the family members may have accents and use ethnic words related to their culture and heritage and it’s very important to get those details right. I talk to my diverse group of friends and ask questions, and I research and make sure I am representing the voices of the characters as best as I can.

Do you ever find ethnic/cultural mistakes in the text you’re reading? What do you do? How do the producers or writers handle the situation?

Yes, I have found mistakes. Sometimes the author may be a quarter of an ethnicity they have written about and their dialog or word choice may be incorrect. Sometimes those details slip by their editor. As you can imagine, their editors are predominantly white and don’t share the author’s culture or heritage. In those cases, I have emailed the author directly and discussed the mistakes; more often than not, corrections are made, unless the mistakes were on purpose to illustrate xenophobic undertones or themes.

Have you been cast in non-ethnic-specific titles? Any differences in performing so-called mainstream titles?

I’ve done quite a few non-ethnic-specific titles and anthologies. There’s no difference in narrating the so-called more mainstream titles: I am still using my same voice and doing it in Standard American. The real difference is that the auxiliary characters do not require accents or knowledge of another language or dialect.

What’s your favorite aspect of narrating? And your biggest challenge?

My favorite is being able to read a lot of great books as part of my job and using my performing background and years of training to bring these books to life. My biggest challenge is the research aspect of getting the voices, accents, and characters right.

Photo by Ash Gupta 838 Media Studio

|

RECOMMENDED LISTENSLee, Krys. How I Became a North Korean. Dreamscape. 2018. Lin, Ed. 99 Ways to Die. Recorded Bks. 2018. Lin, Ed. Incensed. Recorded Bks. 2016. Nieh, Daniel. Beijing Payback. HarperAudio. 2019. Ruff, Matt. 88 Names. HarperAudio. 2020. |

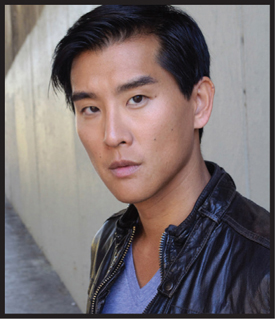

EWAN CHUNG

EWAN CHUNG

Relative newbie Ewan Chung is hard at work building his portfolio, but being a polyglot unicorn—he’s fluent in Mandarin and French, and comfortable with Spanish, German, and more—has him gaining well-deserved laudatory attention.

The first of your audiobooks I experienced was Daniel Nieh’s Beijing Payback. How did you become multilingual?

Beijing Payback felt like the perfect storm for my skill set. My most fluent languages are English, Mandarin Chinese, and French. I was brought up speaking Mandarin at home; I took elementary school Spanish; and I majored in French language and literature at the University of Virginia. I also studied two years of German. I was exposed to a lot of European culture because a third of my family live in the Netherlands. I went over for summer vacation almost every other year, so how could that not influence my ears and tongue?

When I met with my Euro cousins, we were like a mini United Nations. Now as adults, we confidently communicate in Mandarin, English, and sometimes Dutch. Due to this background, I can pretty much cover all of western and northern Europe. French takes care of all the other Romance languages, and German/Dutch takes care of the Scandinavian languages. Slavic languages, Finnish, Hungarian, Estonian, and Greek have been tougher to pick up, but I’m always game to try, especially since I tend to have a good ear.

Your audio debut was in 2015—The Cook, the Crook, and the Real Estate Tycoon by Liu Zhenyun—but you started recording more regularly last year. How did you get into the business?

I had actually been waiting for a long time to break into the audiobook world. The voiceover world in general tends to be a tight group, so you usually have to wait until the right project comes along. Luckily there was a combination of a developing trend of Chinese-themed novels (either written by Chinese American authors or Chinese novels translated into English) and a desire to cast more authentic narrators, especially since these novels have so many Chinese names and phrases involved. This can often mean a lot of cultural research before recording even starts, but sometimes you’re not afforded the luxury of much prep time to begin with! I happen to have traveled somewhat extensively in China and Taiwan, so having any authentic knowledge of place names and dialectal differences lends much more specificity and accuracy to the story.

You’ve done theater, TV, film, video games, commercials, sketch comedy, and you sing! How has that spectrum of mediums influenced your audiobook performances?

I believe any extra skill only helps you tell a story better. I’m all about delineating the characters, especially when there are more than 50 characters in one book alone!

Besides hiring you, how might producers/casting agents ensure aural authenticity?

I would say definitely listen to the preferences of the author. And have people on staff (or access to such people) who can help in making casting decisions. We’re so global now; [it’s important to] recognize authentic language and cultural talent. However, above all else, I believe narrators have to be interested in learning other cultures and details as well. I personally would not want to half-ass anything just out of fear of embarrassment! Last year I had to learn about the Manchu language for the historical fictional podcast, The White Vault: Imperial. That moribund language was very new to me, so you can bet I was hunkering down to get it as correct as possible.

How do you prepare? And now that you’ve worked in quite a few genres, do you have a preference?

I prepare as I would for any project: I familiarize myself with the story and setting, figure out how many distinct character voices are needed, and track the vocal evolution of each character. This is also where I go old-school and work on actual paper so that I can mark who is speaking at any given moment (time, place, age, emotional state). I don’t like surprises because it slows down the narration process for me. Plus, I can’t notate the way I want (especially with various languages involved) on a screen. I guess I’ve mostly narrated crime thrillers, but I’m open to most genres. I like a new challenge each time.

Photo by Toshikophoto

|

RECOMMENDED LISTENSBracht, Mary Lynn. White Chrysanthemum. Penguin Audio. 2018. Cha, Steph. Your House Will Pay. HarperAudio 2019. Han, Jimin. A Small Revolution. Brilliance Audio. 2017. Seo, Mi-ae. The Only Child. HarperAudio. 2020. Wuertz, Yoojin Grace. Everything Belongs to Us. Random House Audio. 2017. |

GRETA JUNG

GRETA JUNG

Relatively new to audiobooks, classically trained Greta Jung was the go-to narrator when a certain author requested a more authentic recording of her South Korea–set title. That success quickly made Jung the Korean American voice of choice.

Your training has been on stage and film. When, how, and why did you cross over to audiobooks?

I actually do audiobooks in between stage, film, and TV jobs. I got into it initially because other actor friends had recommended it as a great way to keep creative in between acting work. As I started getting more work, I found it was also a great way to learn about up-and-coming Asian American writers and Asian American stories.

Since your audio debut in 2012 as part of an ensemble cast, Different Mothers, what major changes, if any, have you seen happen in the audiobook industry, especially for narrators with diverse backgrounds?

I think the biggest change I’ve seen is that there are more diverse stories being published. I also think that authors are being more vocal about having authentic representation in their audiobooks, and more publishers are making it a priority.

I understand you rerecorded a title a couple years ago after the author was dissatisfied with the original (non-Korean) narrator’s performance. That certainly seems to be a significant sign of progress toward authentic representation. In this era of #OwnVoices, do you think authentic representation is truly a high priority for the powers who control the recording studios?

Yes, I do. I think the internet has created a direct line of communication from listener to publisher, so if a narrator’s performance is inauthentic or even offensive, listeners can

voice their opinions in a way that’s hard for publishers to ignore. That’s actually the reason why I was asked to re-record that title. It was from many listeners voicing their opinions about that audiobook online.

As a Korean American with Korean language skills—in addition to knowledge of Spanish and French—what do you do when you come across possible language mistakes on the printed original?

I always speak up. I am very cognizant of doing right by the author because it’s their art that I’m interpreting via voice, but I also do my best to do right by the audience, especially if the art is representing a marginalized group of people. Ultimately though, the decision to change any mistakes is made by the author and publishers.

Do you have any audio mentors?

I owe my audiobook career to Bob and Debra Deyan of Deyan Audio. They were the first publishers to hire me and are always on the ball about authentic representation.

What advice do you have for aspiring narrators hoping to get into the business?

I think the best way to get into the business is to ask another narrator or director for a recommendation. Once you get your first book, I’d make sure to understand the tone of the book and go into the studio fully prepared with all your character voices and correct pronunciations. I use an app called iAnnotate, which has been really helpful in prepping all my books.

Photo by Peter Konerko

Terry Hong writes BookDragon, a book blog for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!