Closer to Home: Libraries Providing Home Broadband

Some libraries have tested WISP Networks and CBRS to explore providing home broadband to their communities, and new satellite technology shows promise for rural libraries.

Some libraries have tested WISP Networks and CBRS to explore providing home broadband to their communities, and new satellite technology shows promise for rural libraries

The COVID pandemic made it clear that access to a fast, reliable internet connection has become a necessity for most people in the United States. Libraries redoubled their efforts to bridge the digital divide during the past three years, with many extending Wi-Fi signals into branch parking lots, expanding Wi-Fi hotspot lending programs, parking Wi-Fi–equipped bookmobiles in strategic locations around their communities, and more. A few libraries went even further, testing ways—other than hotspots—to provide patrons with broadband in their homes.

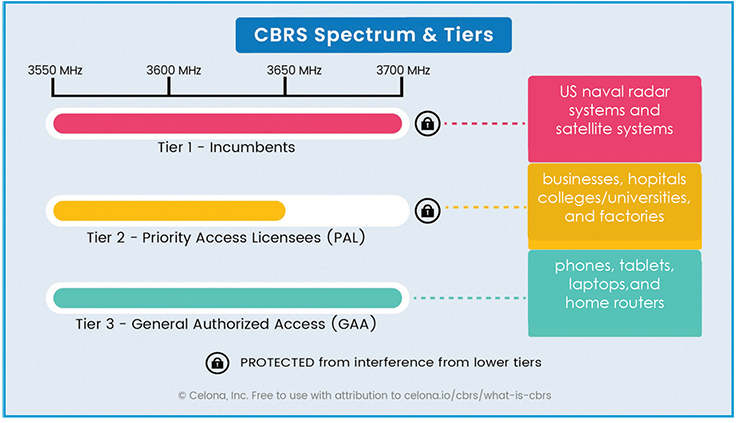

Last year, the New York Public Library (NYPL) became one of the first libraries to test using Citizens Broadband Radio Service (CBRS) to provide 5G and LTE broadband signals free to local households. Not to be confused with Citizens Band, or CB radio, CBRS is a portion of the 3.5 GHz broadcast band that had been primarily used for U.S. Navy radar systems, aircraft communications, and fixed satellite services in the United States. In 2015, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted rules for shared commercial use of the band, and in early 2020 authorized use of CBRS in a three-tiered system. First, a portion of the band is reserved for “Incumbent Access” users, including the military and others that were already using it. Another portion is reserved for “Priority Access” licenses, which are renewable authorizations—purchased at auction—to use 10 MHz channels of the band within individual U.S. counties or census tracts. The third tier is made up of “General Authorized Access” users, who are now allowed to use portions of the band not assigned to a higher-tier user in a given census tract.

Using General Authorized Access bands, NYPL launched a pilot program last spring with the help of a $1.5 million grant from the S&P Global Fund and another private donor, according to the ISP business to business publication Fierce Wireless. With Motorola, Celona, and Baicells providing the antennas and network equipment, NYPL began loaning out home gateways by Inseego and Cradlepoint for patrons to receive the CBRS signals at apartments near the Grand Concourse and Mott Haven libraries in the Bronx; the Countee Cullen branch, the neighboring Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the Seward Park branch in Manhattan; and the Stapleton library branch on Staten Island.

Phase one of the pilot aimed to test the viability of CBRS for getting broadband to local patrons, so NYPL started small, providing gateways to 100 households—20 near each of the five CBRS antenna installations. The library is now entering phase two of the test, Garfield Swaby, NYPL’s VP for Information Technology, tells LJ. “We believe CBRS is a maturing piece of technology,” Swaby says. “It’s not at a point where we can approve operating at scale with it. A number of areas need to be addressed before we can do that. But we’re comfortable with operating the technology, so now we’re looking to expand it to more patrons. In phase one, we focused primarily on the tech. In phase two, we’re going to focus primarily on our patrons.”

NYPL learned several things about CBRS during the first phase of the pilot. The five antennas have a combined coverage range of almost 140 total city blocks; however, the coverage range from one location to another can vary significantly based on the buildings surrounding each branch. “No two locations are similar,” Swaby says. For example, two of the antennas are on branches located near hospitals. One antenna’s range seems normal, while the other’s signal seems to be impeded by its neighboring hospital. “We need to spend some time trying to understand why that is,” he adds.

Targeting patrons who live within a few blocks of five specific branches with this new service proved to be a challenge. “The numbers of people who are walking in and checking out [CBRS] devices is still, to me, underwhelming,” Swaby told Fierce Wireless in July 2022, several weeks after the pilot’s launch. Eventually, “after we installed the antennas, we had to pivot to outreach,” he explains. “We used, over the past summer, a number of [methods] to get the devices in people’s hands.” One of the most successful, he says, was working directly with the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD), which paired NYPL with the managers of an affordable-housing apartment building across the street from the Schomburg Center. NYPL staff set up a table in the lobby to explain the program to interested residents and loan out the home gateways.

|

The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture hosts one of five CBRS antennas used in NYPL’s home broadband pilot. |

CBRS is still relatively new to the commercial and consumer markets, and like most technology, the cost of devices will likely decline if adoption becomes widespread. For now, though, Swaby says that it is prohibitive for a large-scale program. “I don’t think the price point for the home devices will be sustainable over the long haul, for us or any other library,” he says, noting that a vendor recently charged NYPL $600 for each of three unreturned gateways that were used in the first phase of the pilot. “Even if we were going to get these at list, they would be $500 to $600, plus an additional $100 management fee,” he says. He is looking into alternatives, such as gateways that broadcast Wi-Fi floor-by-floor in buildings near branches equipped with CBRS antennas.

In addition to working with HPD, “we’re in conversations with community organizations,” Swaby says. “We’re looking at a partnership with CTNY [Community Tech NY]—I really like their approach to grassroots digital justice. We’re looking to incorporate their digital navigator and digital stewardship model for engaging folks in the community, so we can teach them about the technology and have people from the community to help [other] people in the community with tech support and troubleshooting and general, basic information around technology.”

FIXED WIRELESS ISP

With the help of a $492,000 Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) CARES Act grant, North Carolina’s Charlotte Mecklenburg Library (CML) developed its MeckTech Connect pilot program with Open Broadband, a regional ISP focused on underserved communities. Using outdoor fixed wireless antennas in locations throughout Charlotte’s West Boulevard Corridor—a neighborhood where broadband adoption had been below 50 percent—the program aimed to offer free home wireless broadband connectivity to households in the area for a year in 2022. In addition to the IMLS CARES grant and Open Broadband, the program was made possible with the support of local partners including Bloom, City Startup Labs, the West Boulevard Neighborhood Coalition, Hack & Hustle Academy, and RowdyOrb.it.

“While the MeckTech Connect initiative is still active, the library’s role in the project has changed significantly” since the pilot program concluded, says Krystel Green, chief marketing officer for CML. “Although the Library was able to establish a WISP [Wireless Internet Service Provider] network and was able to connect 64 households to free Wi-Fi for a year, expansion of the network was delayed [owing] to personnel changes, supply-chain issues, and permitting delays. However, these residents will gain internet connectivity through the city of Charlotte’s Access Charlotte program. The city of Charlotte was established as a partner in this project early on, and [its] adoption of the connectivity aspect allows the library to focus on digital literacy services in the area. This creates a much more sustainable model, which means less disruption and [fewer] changes for the residents.”

Approximately 800 households in the neighborhood can now use the WISP network via Access Charlotte, and “these households can take advantage of a variety of library resources, including eligibility for free refurbished laptops through the library’s MeckTech laptop distribution program,” which has distributed more than 8,000 free, refurbished laptops to Charlotte residents so far, and has a goal of distributing a total of 20,000 by the program’s conclusion in May this year, Green says. “This places the library in a natural position to offer digital literacy services and continue to create pathways for successful experiences for technology needs these residents may have.”

RURAL SOLUTIONS

While CBRS and WISP networks may provide access to a large number of households in urban areas, many rural and tribal libraries have to work with spotty service from commercial ISPs. In some cases, libraries have taken service issues into their own hands. Prior to the pandemic, the Middle Rio Grande Pueblo Tribal Consortium and the Jemez and Zia Pueblo Tribal Consortium in New Mexico laid several miles of cable for two tribally owned and operated fiber-optic networks to provide broadband to libraries and schools in six pueblos, with the help of $3.9 million in E-rate funding. The project broke ground in late 2017. More commonly, however, a rural public library—along with other local anchor institutions such as schools—will need to source the best solution available to its service area, and often will be the best public option for local residents who need broadband access.

|

In 2020 the FCC authorized the use of CBRS in a three-tiered system, enabling commercial use of the spectrum for 5G and LTE broadband. |

“In some cases, the library is the only free place for Wi-Fi access in the community—whether it’s a rural community or a tribal community,” notes independent Library Technology Consultant Carson Block, adding that “one thing we have learned during the pandemic is that there’s a high demand for connectivity in all of its forms,” and that libraries should explore whatever options are available locally to help patrons.

TV WhiteSpace (TVWS) is being used by many rural libraries to extend their broadband signals within their communities. Utilizing unused bands of the radio spectrum that are traditionally allocated to television broadcasters, these libraries mount an omnidirectional base station antenna on the building’s roof or in another strategic location outside the library and connect the antenna to the library’s broadband.

While the solution isn’t currently scalable to provide home broadband access to all households throughout a rural community, portable remote client radios/receivers placed up to six miles away from the base station can receive the signal and broadcast Wi-Fi locally in gathering places such as community centers, special events venues, other anchor institutions, and more. (Some equipment manufacturers advertise that their client radios can be used up to 24 miles away from a base station.) Speeds will vary based on the broadband speed at the library, the equipment used, and other factors, but newer client radios can reportedly offer Wi-Fi download speeds of up to 50Mbps. Prices vary by project, but in 2021, LJ reported that a rural library in Minnesota had been given a quote of $9,000 to $13,000 for three base stations and five client radios/receivers. The Gigabit Libraries Network (GLN) has been working on TVWS projects for a decade already, and through multiple sub-grants, pilots, and rollouts in multiple states has demonstrated the technology’s usefulness for rural libraries as well as its necessity during natural disasters and other events that require community anchor institutions to communicate with one another.

GLN’s latest project is LEO Libraries, which is testing the utility of Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites for broadband in rural regions. In late January, GLN announced an agreement with the Nigeria National Library to test SpaceX/Starlink’s LEO broadband systems at five public libraries in the country. GLN Director Don Means notes that satellite internet connectivity has been available for a long time, but describes older, geostationary satellite internet providers as “the source of last resort for people in remote rural areas,” since they tend to have issues with interference and latency/lag.

By contrast, the advent of LEO satellites—Starlink is currently the leading service provider, although Amazon’s Kuiper Systems is planning to launch its own LEO network soon—has made it possible for homes, businesses, libraries, and other institutions in rural areas that aren’t served by fiber-optic or cable broadband to pay for low-latency broadband with speeds of 50 to 500Mbps. The latency is typically “20 to 40 milliseconds, which is entirely fine for almost every kind of application,” Means says. “And the speeds have been impressive, hundreds of megabits per second compared with 10” with geostationary satellites.

The equipment is also easy to install. “The whole thing comes in a box, and it’s mailed out to you,” Means says. “It’s a [satellite] dish with a power cable, 100 feet of ethernet cable, and a bundled router. You just plug it in. You set the dish out in open sky…and it announces itself to what they call the constellation [of LEO satellites] overhead…and bang, you’re live with a 100MBps connection within minutes,” he explains, noting that the Starlink satellites also have heating elements to melt snow and ice during the winter, and motors that move the dishes to get the best reception.

Means does note that one major impediment to the widespread adoption of Starlink is the service’s ongoing cost. Residential customers pay $110 per month, with a one-time hardware cost of $599. However, rural businesses and institutions such as libraries—which will often be serving multiple users at once—might need the company’s enterprise hardware, which promises speeds of up to 350 Mbps and latency of only 20-40ms for up to 20 simultaneous users. That comes with a one-time hardware cost of $2,500—for a higher-gain antenna, additional throughput allocation, and better extreme-weather performance than the residential equipment—and a monthly service bill of $500.

Concerns about cost and long-term program sustainability were topics that came up in every conversation about libraries doing more to provide broadband access. Libraries have been working to address the digital divide and the availability of reliable internet access in their communities for decades, but COVID made these issues more obvious to politicians and the general public. Grant-funded pilots proving the viability of different solutions for improving local access, whether or not they’re picked up by local municipalities as CML’s MeckTech Connect was, deserve continued exploration.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!