How to Articulate Your Library's Impact and Get What You Need

Whether lobbying legislators for funding libraries or a foundation for new shelving, public library leaders, communications staff, and even frontline workers need to be efficient and nimble when articulating their impacts to outside stakeholders. Crucially, they need to approach the question from the vantage of how the library’s outcomes align with that particular stakeholder’s mission.

Making an effective case for the library’s work to funders, elected officials, or community partners calls for a targeted, well-crafted message—and knowing your audience

Whether lobbying legislators for funding libraries or a foundation for new shelving, public library leaders, communications staff, and even frontline workers need to be efficient and nimble when articulating their impacts to outside stakeholders. Crucially, they need to approach the question from the vantage of how the library’s outcomes align with that particular stakeholder’s mission.

Articulating your library’s impact requires a convincing combination of data and narrative, tailored to reach the right supporters by addressing the issues they care most about. Funders, government officials, nonprofit partners—all look for specific demonstrations of the library’s value, and all have different agendas. Best practices can make sure that the supporters libraries most need to reach will hear them.

KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE

Advocates should learn as much as possible ahead of time about the individual or organization being approached: the issues they care most about, their connection to the library, specific ways they can help.

Much of that baseline knowledge starts with identifying the library’s relationships with its stakeholders. Lance Werner, director of Michigan’s Kent District Library (KDL)—and LJ’s 2018 Librarian of the Year—has seen widespread success advocating for his system and libraries across the state to legislators, local business owners and CEOs, county commissioners, state library association administrators, LIS educators, and patrons. He chalks it up to having developed and maintained relationships with as many potential allies as possible. “People know me,” Werner says, “because I took the time to establish a relationship with pretty much everybody in the county.”

That doesn’t happen overnight, however. “I called people up, I invited them for coffee, I listened more than I talked,” explains Werner. “I got a good sense of who they were. And I did my homework—I had some background information about them before I started.”

Those connections are important not only when it comes to funding, but for a wide range of troubleshooting, backup assistance, and problem-solving. “When an issue arises, when something comes up, I have that foundation,” says Werner. “I’m not coming to them in my time of need like a telemarketer.”

The relationships are reciprocal, notes Werner. “They call me too, so it works two ways. If they have an issue I can help them with, then I’m happy to. It’s give and take.”

|

SEEING CLEARLY Vision to Learn (VTL) and Cobb County Public Library staff with VTL’s mobile clinic van. Photo courtesy of Cobb County Public Library |

PERFECT THE PITCH

Relationships, of course, are only the first step. No matter how personable the connection, the library needs to be able to clearly articulate its successes and needs.

When Tom Brooks, communications specialist at Cobb County Public Library System, GA, first read about Atlanta Regional Commission’s What’s Next ATL initiative, which sought to address ten citywide challenges through opportunities for community engagement, he knew the library would be a valuable partner.

Brooks combined stories of the library’s previous work with local health and literacy statistics to make a case for the library to host programming that turned out to be well-attended, including Vision to Learn, which provides free eye exams and eyeglasses for children. Once the nonprofit began screenings at the library, he contacted the local press—which was happy to cover a positive, community-centered story.

Keeping library services front and center in the news, says Brooks, a former journalist, “is a lot more than just a feel-good story. It’s changing the conversation.” When documenting the library’s accomplishments, communications staff should think like journalists to find the best platforms and contacts—and reimagine how to package that information for other outlets. A story on programming can connect to the civic cost of isolation among older residents: “Book discussion groups and knitting groups have outcomes too,” Brooks notes.

“Don’t be intimidated. Strive to [learn from] the experts even if it’s really technical and challenging,” he says. “Bringing these conversations out from the specialists and experts is important.”

ADVOCACY AT THE TOP

ADVOCACY AT THE TOP

When it comes to making the library’s case to elected officials, Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI), who sponsored the bipartisan Museum and Library Services Act of 2018, suggests first developing a plan outlining who to speak with and when. “We’ve got to contact the state leaders, the governor, and legislative leaders. Then we want to talk to our congressional delegation. Also we probably want to talk to philanthropic organizations, not just to ask for money but to show them how critical libraries are. Then we want to talk to the business community about the role of libraries. And obviously you want to tailor the stories and the data to your audience, but it has to be systematic and confident.”

Make sure you have identified all the elected officials who affect the library, he advises. “At the state [level], that would be the leadership of the state Senate, the State House, the committee chairperson who is in charge of authorizing and funding libraries, the state library official, and the governor’s office. You put all that in a hierarchy of how you want to proceed.”

Leglislators’ staff play a critical role, he adds, so it’s important that the library’s message reaches them as well.

ISSUES ARE A WAY IN

“Libraries have an advantage in that they are often the cornerstone of their communities, and everybody recognizes that,” says John O’Brien, director of communications and senior policy advisor at the Pennsylvania House Appropriations Committee. Legislators “know the libraries in their district, they most likely grew up going to them, they have that kind of nostalgic connection.” Listening closely to what legislators are talking about here and now—such as the 2020 census, workforce development, rural broadband, and other concrete examples of current, real-world impacts—and then tying the library’s work to ongoing political concerns, he says, “helps connect to the message of why funding libraries at a higher level is important.”

Reed notes, “The more you go up the governmental chain of command, the more local you have to make [your advocacy] to be effective.”

That means demonstrating that value in person, and on site. “Have a library invite their local legislator to the library and show them what they’re doing—not just taking them on a tour of the building, but show the programmatic stuff that they’re doing, and why that’s important,” O’Brien suggests.

Don’t be a fair weather advocate, he adds. “In the capitol, you usually hear from special interests—everybody who’s looking for something—during the time that you’re crafting the budget. Then as soon as the thing’s passed, you don’t hear from anybody for the next months,” O’Brien says. “It’s noticed.”

You’ll also have less competition. “If you wait until the month that a lot of state capitols are in their crunch time for passing a budget, you’re trying to make some noise with a lot of other people and it’s hard to get your story across,” he notes. “But if you’re continually doing that outreach, you form more of a bond and more of a relationship, and a better chance of your story being heard.”

|

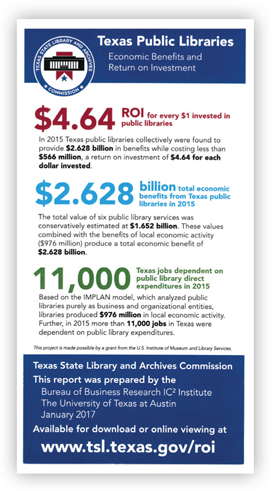

STATS AT A GLANCE ROI infographic from the Texas State Library demonstrating the benefits of investing in public libraries |

GO BIG

Last year, LJ noted in "Get That Grant" that more than 7,100 funders gave over $586 million in grants to libraries. From small matching donations to long-term, multi-million dollar awards, there is a grant-maker to fit every library’s needs. (For tools and guidelines, see libraries.foundationcenter.org.) As libraries are increasingly asked to do more, many foundations are eager to help—especially when missions such as access and equity serve funders’ objectives as well.

It may sound counterintuitive, says Darryl Tocker, executive director of the Austin, TX–based Tocker Foundation, which supports rural public libraries across the state, but when it comes to seeking grants, libraries should be wary of selling themselves short to prove that they’re good stewards of community money. Funder asks should be reasonable, but also reflect realistic expectations of programming and service costs.

“Librarians are frugal, and they can stretch a dollar further than any administrator I’ve seen,” says Tocker. “They’re always trying to get by the next year; we’re trying to fund them for the next ten years. Instead of adding on another row of shelving, let’s look at your footprint altogether. Let’s look at your floor plan. If we’re going to do something, let’s rethink the whole space.”

The Foundation works with a grant review committee appointed by the Texas Library Association, but Tocker notes that because its funding is geared more toward operations than innovation, it often sees similar projects and is willing to work with libraries on their grant applications. “We have a lot of knowledge about how a project can be enhanced, or brought up to a standard where we will fund it,” he explains.

EVALUATING OUTCOMES

There are a number of tools that libraries can use to collect data and translate it into meaningful advocacy.

Whereas library data has long been measured in terms of output—circulation, checkouts, program attendance, door counts—outcomes can be quantitative, qualitative, or both. The Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) has extensive guidelines for outcome-based evaluation measuring “benefits to people: specifically, achievements or changes in skill, knowledge, attitude, behavior, condition, or life status.”

The Public Library Association (PLA) developed its Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation–funded Project Outcome tool in 2015. Its standardized surveys can be distributed after a program or service. According to Project Outcome’s 2016 Executive Summary, more than half of respondents said that it helped the library have a bigger impact. (See LJ’s roundup of outcome measurements, “Meaningful Measures.”)

As libraries become more efficient at capturing outcomes, stakeholders are more attuned to them as well. “They’re becoming more sophisticated,” says Cuyahoga County Public Library (CCPL) Communications and External Relations Director Hallie Rich. “They want to know, ‘You saw 500 people, so what?’”

It’s also worth remembering that most stakeholders are, in turn, accountable to the organizations and agencies that oversee them—which means documenting the results of their work with libraries. Having clear outcomes-based evidence of success not only serves libraries making their case, but their potential partners. Congress requires IMLS to document results of its grant activities annually, and IMLS uses grantees’ reports to demonstrate libraries’ impact on their communities. Funders need to know that most of the money is flowing through to the end user—“changing people’s lives, addressing an issue, and making a difference,” says Tocker.

ROCKING ROI

Return on Investment (ROI) is used to evaluate the efficiency of an investment. ROI can be a useful, flexible way for libraries to demonstrate their impacts, especially when combined with other valuations.

The San Francisco Public Library (SFPL), LJ’s 2018 Library of the Year, began leveraging its ROI metrics in 2015, when the system completed its 14-year Branch Library Improvement Program. The city Office of the Controller released an impact study detailing the economic benefits and ROI that the program stimulated throughout the city. The report, “Reinvesting and Renewing for the 21st Century,” analyzed four measures of community benefit: collection expansion, technology resource improvement, increase in community meeting space, and service expansion via community partnerships and programs, as well as an economic benefits analysis, 25 stakeholder interviews, and reviews of the literature, including the two bond measures that funded the program. All possible metrics, from construction costs to library service assessment, were taken into consideration.

The study revealed that for every dollar invested in the program, San Francisco realized a return of $5.19–$9.11. Capital investments and additional operating spending contributed more than $330 million in indirect and induced benefits to the city’s economy.

“It’s a tool that folks are going to take interest in if they’re looking at potential capital projects,” former City Librarian Luis Herrera told LJ when the report was released. “Any city or county, any jurisdiction could use [it] as a framework.”

These are useful metrics for libraries to present to elected officials as well as funders. “Whenever we talk about what areas of the state budget that we’re going to fund, Return on Investment always comes up, whether it’s in education, human services, corrections, other public safety matters, and with libraries,” says O’Brien. “We invest this money—what is the public expected to get out of that?”

THE VALUE OF MARKETING

THE VALUE OF MARKETING

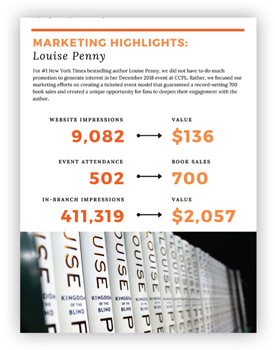

Ohio’s CCPL has developed an even more targeted ROI initiative, using data to measure the impact libraries have on driving book discovery, developing readers, and generating book sales. The Value of Author Marketing Calculator—a spreadsheet developed by Rich to rebut Macmillan’s claim that libraries were “cannibalizing” book sales on the heels of its ebook embargo last fall—allows libraries to enter information such as website page views, email marketing distribution and opens, in-branch marketing, social media, and paid advertising to calculate the total marketing value of an author event.

The impetus behind its development, says Rich, “was looking to quantify what is the value above and beyond the hard dollars that libraries invest in purchasing collections—what other value do we provide to publishers and to authors through our work?”

Using CCPL as an example, Rich and members of the library’s IT department mapped out the communications and marketing touchpoints involved in author visits, assigning values to them. “When we started to quantify, our email list [had] over 250,000 addresses,” explains Rich. “The open rate is x, I can assign a value to it because I know what I would pay for cost-per-thousand impressions for an ad to be delivered in someone else’s email marketing system.” She also looked at what the library does to pitch stories about authors coming to speak, curated book lists created by staff around author events, and paid media such as CCPL’s monthly and weekly TV spots. Book sales opportunities are also taken into account.

The team shared the spreadsheet with the American Library Association (ALA) for feedback; ALA now includes it, along with instructions and a sample report, as a resource on its #eBooksForAll webpage. It can be used and modified by all kinds of libraries, says Rich. “Even if you’re a small system, if those libraries are creating branch signage—which, if you’re paying for outdoor advertising, is essentially what that becomes—there is a value for that. Libraries of any size are hosting a website where they’re featuring different books and authors. Libraries of any size are hosting events where they’re bringing in customers to engage directly with an author.”

NARRATIVES VS. NUMBERS

There is no exact formula for the proportion of data to story. That ratio is probably more art than science, but both need to be present. “You’ve got to have the numbers,” says Reed. “But I think what’s most engaging is the story. That grabs the attention and the imagination.”

The library should already have many of the necessary numbers in its annual report or can pull records from the state library and associations. By lining up a few reports, says Tocker, “You can see the volume change from year to year easily. The metrics of how much a dollar invested in the library returns to the patrons of that municipality—that information’s been quantified.”

|

SAVING LIVES AND DOLLARS Cobb County Public Library’s Falls Prevention Awareness webpage highlights the cost of falls among older adults, and how the library can help |

When advocating for Cobb County Library System’s participation in the What’s Next ATL initiative, Brooks reached out to several community nonprofits with health and literacy statistics gathered from sources ranging from GIS and census tract data to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ OASIS-D data sets and statistics from the Emory University Injury Prevention Center. He was able to repurpose those figures for advertising the programs to the public as well—flyers for the Falls Prevention programming noted that ten people 55 and older go to the emergency room every day due to falls.

But numbers alone won’t do the trick, Brooks says. “You have to put the ‘why’ out there.” Data is not one-size-fits-all information, and its utility can vary across communities, cities, or states. With stories, he notes, “You’re putting a face on it.” And narratives can be reworked for emphasis, depending on who is being pitched, without losing accuracy.

“Storytelling is a huge component,” notes Werner. “It’s important to be truthful, but you can tell the story that you feel is going to resonate most with whomever you’re speaking. Tell stories that touch your heart, things that you’re emotional about, things that you’re passionate about.” Allowing that subjectivity into the conversation keeps it real, Werner believes. “It resonates. That is impactful and that is how things get done.”

|

BOOSTING BOOK SALES Cuyahoga County Public Library’s Value of Author Marketing Calculator returns a dollar value on the work a library does for visiting authors |

“PURISTS GO HUNGRY”

No matter how strong the message, however, it’s not always going to accomplish what it set out to do—which is an acceptable part of the process. An all-or-nothing approach can backfire. “We usually say up here in Harrisburg that ‘purists go hungry,’” notes O’Brien, “and that when it’s my way or the highway, often nothing gets done.”

“Let’s say the library organization wants $10 million more in their budget, and the legislature is able to get them $5 million,” he says. “That’s not everything the libraries wanted. But it’s a positive step forward. And it’s important to make that acknowledgment that yes, we’re still going to push for more, but we want to thank the legislators for partnering with us and getting us more resources. Everybody enjoys being thanked, and that positivity helps you continue to push your message forward.”

“You will get turned down a lot,” says Tocker. “But you have a lot of funders out there that would see the value in the library and would jump at the chance to fund a project or program.”

If advocacy runs into red tape, or a straight-up “no,” use that roadblock as a chance to refine your strategy going forward, says Werner. “It’s important to keep asking the questions,” he says: “‘I understand you can’t help me, but who do I need to talk to?’ ‘What would have to change?’ ‘Could you please give me more information about how we might package this differently?’ Ask for feedback from the people that you’re running up against, and have them guide you on your next moves.” Often those on the front lines, rather than the decision-makers, will have better guidance on those issues, he notes, as they are privy to the entire process.

If advocacy succeeds, that doesn’t mean the questions should stop. Libraries should always ask for input from the foundations they work with, notes Tocker, whether their grant applications succeeded or failed, or just fell short of the desired goal. Funders have their own networks, and asking the right questions can often lead to a good fit.

With all the possible combinations of data and stories, resources and recipients, the possibilities for effective advocacy are wide—and can appear complicated at first. If there’s a rule of thumb, it’s to pare down to the essentials. “In libraryland we have a tendency to overtalk things,” says Werner. “Whether you’re talking to somebody about funding a project or getting a bill introduced into the legislature, it’s important to be very simple and concise, and to be able to convey what you’re trying to say directly.”

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!