To Tell the Truth: Public Libraries in the Fight Against Misinformation, Disinformation

Providing accurate and reliable information is a cornerstone of public librarianship, but over the last year librarians have been especially challenged by the pandemic, the election, and the increased visibility of conspiracy theories. Nonetheless, public librarians remain active on the front lines of the fight against misinformation and disinformation and continue to seek out new and more effective ways of helping their patrons apply information literacy principles in their daily lives.

How public librarians are tackling the increasingly complex challenge of misinformation and disinformation

How public librarians are tackling the increasingly complex challenge of misinformation and disinformation

Providing accurate and reliable information is a cornerstone of public librarianship, but over the last year librarians have been especially challenged by the pandemic, the election, and the increased visibility of conspiracy theories. Nonetheless, public librarians remain active on the front lines of the fight against misinformation and disinformation and continue to seek out new and more effective ways of helping their patrons apply information literacy principles in their daily lives.

Glenn Harper, a public librarian from Melbourne, Australia, runs a “Fake News” program inspired by inoculation theory. Pioneered by social psychologist William J. McGuire, the theory posits that beliefs can be safeguarded from outside influences if people are given the opportunity to practice refuting insubstantial arguments—much as vaccines protect the body by exposing it to a weakened form of disease. In his course, Harper asks attendees to evaluate 10 actual social media posts, responding with “like” if they believe the story is accurate, “dislike” if they deem it false, or “share” if they think the content not only true but worthy of being sent to a friend or colleague. Afterward, Harper goes over which stories were true and covers fact-checking tips.

He explains, “The idea is to expose people to some ways that social media posts can be misleading and manipulative in the hope that the next time they see something similar, they are alert to both the techniques and their own biases, impulses, and logical fallacies.”

The “Fake News” program is promoted on the library’s website and social media, and Harper has run it at other libraries, too. “I see light bulbs go off as people realize that they accepted a falsehood or could have fact-checked but didn’t. I think that’s the biggest takeaway for a lot of people: Pause and fact-check before sharing or liking.”

BETTER TOGETHER

BETTER TOGETHER

Developing partnerships with other organizations can help increase reach, get accurate subject-specific information for patrons, and build awareness and civic trust in other, less visible, public institutions. For example, last September, in preparation for the 2020 general election, the Cook Memorial Public Library District (CMPLD), Libertyville, IL, hosted a Zoom program in which Lake County Clerk Robin O’Connor discussed the vote-by-mail process. She cleared up misconceptions; when a patron asked how to tell whether an electronic vote had been registered, O’Connor emphasized that votes cannot be cast online.

Many people already trust the library, Nate Gass, emerging technology librarian at CMPLD, says. “If you can sow a little more trust back into other civic institutions with library programming, that credibility built through community dialogue and education is another tactic toward battling misinformation.” Haley Samuelson, reference librarian, hopes that CMPLD can run a similar program in which a local journalist will discuss the ins and outs of reporting a news story (Gass and Samuelson are 2020 LJ Mover & Shakers).

Paula Brehm-Heeger, Eva Jane Romaine Coombe Library Director of the Cincinnati & Hamilton County Public Library, notes that her institution has worked with a number of other organizations—by partnering with the Christ Hospital School of Nursing, the library provided wellness checks and health literacy information, and the library is in talks with the University of Cincinnati Health Sciences Library, with the goal of hosting a presentation by medical doctors or epidemiologists to promote vaccine acceptance.

The Evanston Public Library (EPL), IL, collaborated with Evanston Latinos, a local organization that works with immigrants, including those who are undocumented, to provide a “Resilient Household” class for Spanish speakers on COVID-19, finances and budgeting during the pandemic, technology, state and local government, and community resources.

“That really helped us start a relationship,” says Supervising Librarian Miguel Ruiz. That’s crucial when it comes to ensuring libraries reach traditionally underrepresented communities. EPL is located in the city’s community center, and one of the class’s attendees mistakenly thought that library patrons had to belong to the center to have a library card. Building relationships, says Ruiz, is crucial to removing barriers preventing members of the community from even entering the library.

Libraries must also be aware of the digital divide, cautions Ruiz. Though events are now held virtually, in the case of the COVID relief classes, EPL made an exception “in the name of equity,” says Ruiz. “While everyone was going virtual, communities were leaving behind folks who didn’t have those digital literacy skills or didn’t have access to resources such as computers, laptops, the internet. We recognized that having Zoom classes was not going to be the best fit for the population we were trying to reach.” Each class was limited to 10 people, and students and teachers socially distanced and wore masks.

|

|

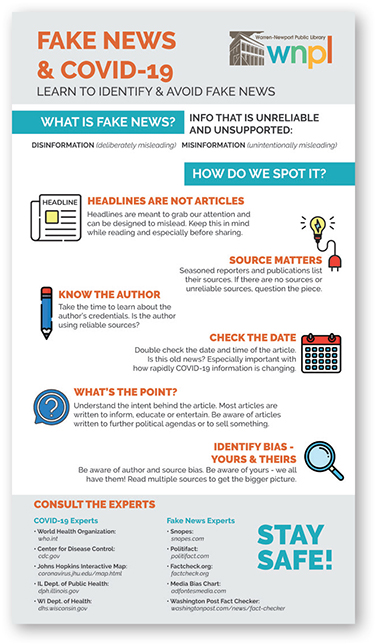

SPREADING THE WORD A flyer from the Warren-Newport Public Library offers tips for fact-checking COVID-19 info. Flyer courtesy of Warren-Newport Public Library |

BIAS AND NEUTRALITY

Though it’s standard for many libraries to present clear and accurate, nonpartisan information on elections, tackling political misinformation often means wading into murkier territory. Adult Services Librarian Rachel Murray, Programming Specialist Madelynn Austin Lehman, and Readers’ Advisory Librarian Jessica Stalker run information literacy classes at Warren-Newport Public Library (WNPL), Gurnee, IL. They don’t avoid exploring examples related to politics in their classes—for example, they sometimes unpack the false claim that Ford moved its vehicle production to Ohio from Mexico following Donald Trump’s 2016 election win; in actuality, some manufacturing operations were moved in 2015, before the election, as reported by CNNMoney.

However, the librarians stress that they’re not here to tell patrons what to think. WNPL serves individuals from across the political spectrum, and librarians want attendees to form their own opinions. Murray notes, “We’re not denigrating anybody, we’re not coming down on anyone’s political beliefs.” She finds the Ford example useful because it is “more of a neutral political mention than a discussion of political ideology. It doesn’t condemn any political view; it simply shows how framing a topic in a specific light at a specified time can change the overall meaning of a story.”

Though the WNPL librarians don’t tailor their presentations by audience, Murray says that they “review each example from a ‘devil’s advocate’ point of view. If we feel that someone could take offense to an example, then we choose a different example to avoid hard feelings or misunderstanding.”

While Jessamyn West, library technologist in Orange County, VT, understands the desire for a balanced point of view, she says that isn’t always possible. In the United States, many assume it’s important to present both sides of issues such as abortion or the death penalty, West says, but in other parts of the world, even the assumption that these topics are up for debate is taking a stance.

West stresses that neutrality also posits a world where words or ideas can’t cause harm. “I think many, many people are in situations where words can hurt them,” she says, citing microaggressions in the workplace or conspiracy theories, such as those that led to the Capitol insurrection.

Says Gass, “We all carry bias with us, and neither journalists nor librarians are exempt from this. The notion of objectivity can be used to reinforce predominant narratives that might actually need to be challenged or questioned with good reporting from diverse perspectives.” Gass adds, “That’s not to say all claims are equally valid or should be treated as such, but when it comes to teaching media literacy it’s perhaps more important to start with how to identify bias in ourselves and what we consume, rather than try to pretend there are sources that are somehow entirely neutral. Then we can begin teaching the importance of seeking out reporting done honestly and accurately, how to sort out opinion pieces from reporting, and how to gauge credibility.”

WOVEN INTO THE LIBRARY—AND BEYOND

How can librarians reach individuals who need information literacy help yet aren’t interested in attending classes or presentations? It’s a question with which librarians are still grappling, but Gass and Samuelson believe that weaving information literacy into all elements of the library’s work is part of the answer, such as demonstrating research skills during reference interviews. One of Samuelson’s colleagues was asked if Joe Biden was wearing an orthopedic boot to conceal an ankle monitor because he was under arrest for treason. Though initially inclined to shut down the question, the librarian instead showed the patron how to research the topic and that all the outlets she consulted stated that Biden had incurred a hairline fracture while playing with his dog. Samuelson notes, “The patron thought she would give a ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ And she said, ‘No, I research everything before I answer.’”

Librarians can also practice what they preach by citing sources in everyday conversations. “It’s good practice, whenever you’re saying, ‘I heard this’ or ‘I read this’ or ‘Did you hear about this’ to throw in where you heard it,” says Gass. “It’s demonstrating and exemplifying what it means to be someone who cares about where their information comes from.”

West says that engaging with the public outside the library can be beneficial. She spends time on social media “pushing back against narratives that are factually wrong.” On Facebook, she talks with people she knows, many of whom are older, white, and conservative. She’s explained, for instance, why it’s neither helpful nor appropriate to ask Black Lives Matter protesters to be “nicer” in their messaging.

“People trust me not because I’m a librarian but because they know me and I’m their neighbor,” she says. “They know I would help them if they were in trouble even if they despise what I stand for, and as a result, maybe they’re a little more primed to learn from me.”

Whether librarians are meeting patrons in the physical library or outside, cultivating a sense of trust is crucial. Says Ruiz, soft skills are especially important when dealing with those who may feel uncertain in the library’s space. “Strong interpersonal skills, being able to connect with people—those are the things that are crucial to serving as an information hub. That leads to people trusting you.”

| See more of LJ's coverage on libraries helping to fight misinformation at In the Classroom, In Life: Academic Librarians Combat Misinformation On Campus and Off and What We Miss About Misinformation: Q&A with Dr. Nicole Cooke. |

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!