Restorative Libraries: Restorative Justice Practices and How to Implement Them

Restorative justice is broadly defined as an approach to repairing and addressing harm done within a community. It can also be understood as a practice that emphasizes the importance of every voice being heard when harm is done, in order to repair the holistic well-being of the person harmed, the person responsible for the harm, and the community impacted by the offense. These methods are used proactively and are foundational in creating systemic change within any organization.

|

HAIRCUTS AND CONVERSATIONS Patrons wait to get haircuts at OPPL's Leading Edge Barbershop. Photo By Kristen Romanowski |

Oak Park, IL, exemplifies the benefits of a restorative justice and practices approach to community engagement and public safety

One Saturday in 2014, I was meeting with a men’s group at the Oak Park Public Library (OPPL), in a suburb of Chicago. We had an unpleasant interaction with a staff member that made us feel unwelcome and patronized. I shared my experience with the library’s executive director, David J. Seleb, in an email, and he invited me to his office for a conversation.

Having had 10 years of experience as a restorative justice practitioner, I recognized a restorative approach when I saw it. Seleb responded to my concerns, and three things stood out. He responded promptly, indicating my concern was a priority. He invited me to his office to have a conversation about my experience, which let me know he was interested in engaging on a deeper, more personal level, as opposed to responding via email. And he was receptive and listened to my concerns as I shared my experience, which was validating and affirming.

I knew that he took my concerns seriously because he didn’t jump to conclusions, didn’t seek to place blame, and extended an opportunity to connect with me as a person on a relational level as we navigated the issue. Everything about that experience epitomizes what restorative practices are about.

Less than two years later, I became an employee of OPPL, working closely with the library’s first social worker, now Director of Social Services and Public Safety, Robert Simmons.

|

RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN ACTION Dr. Troy Washington facilitates a conversation with panelists at OPPL's 2018 Restorative Justice Conference. Photo by Stephen Jackson |

WHAT ARE RESTORATIVE JUSTICE AND PRACTICES?

Restorative justice is broadly defined as an approach to repairing and addressing harm done within a community. It can also be understood as a practice that emphasizes the importance of every voice being heard when harm is done, in order to repair the holistic well-being of the person harmed, the person responsible for the harm, and the community impacted by the offense. Restorative justice can consist of processes like victim-offender mediation, conferencing, or offender assistance programming. While restorative justice is generally reactive in nature, restorative practices are deliberate and proactive approaches that aim to strengthen relationships between individuals and the communities they belong to. Rooted in restorative justice philosophy, restorative practices focus more on preventative action and ultimately inform how individuals engage and interact with one another.

These methods are used proactively and are foundational in creating systemic change within any organization. Jeanie Austin, a librarian at San Francisco Public Library (SFPL), describes restorative practices as “a practice that can transform libraries.”

An example of a restorative practice at OPPL is the Leading Edge Barbershop, which we hosted from 2018 until the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Staffed with local barbers who give free haircuts to community members, the barbershop provided opportunities for library staff and others to build relationships by using peace circles to facilitate conversations with the public that otherwise may not have occurred. Peace circles, described by author Kay Pranis as a “structured dialogue process that nurtures connections and empathy, while honoring the uniqueness of each participant,” stem from First Nations and Indigenous cultures and are rooted in the interconnectedness of life. These conversations strengthened relationships with the community and participants.

Both restorative justice and restorative practices are strategic methods that involve people, engagement, dialogue, and action. While the two can sometimes be used interchangeably, it’s important to understand that many restorative practitioners see these approaches along a continuum, from informal acts, such as affirmative statements and asking questions that suspend judgment, to more formal actions, such as mediation and conferencing to bring together people and discuss incidences of harms or address conflict.

|

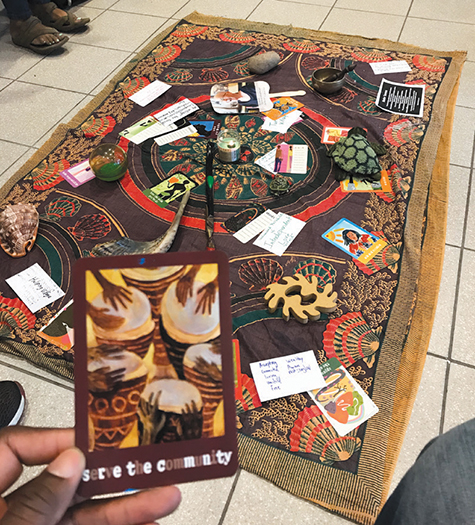

COLLATERAL GOODS Materials from OPPL’s 2018 Restorative Justice Conference’s youth panel laid out . Photo by Stephen Jackson |

VALUING COMMUNITY ASSETS

In 2016 I came on staff at OPPL after being recruited as part of a fairly new initiative to integrate social services within the library. Along with Simmons, I was hired to embark on a journey of identifying and addressing the needs of some of Oak Park’s most vulnerable populations.

At that time Simmons and I had more than 15 years combined experience working in the Oak Park community. Under his direction, the library integrated public safety with social services into one department, a deliberate move given that many patrons who encountered public safety staff also belong to underserved and marginalized populations, particularly teens, unhoused individuals, and those experiencing mental illness.

The aim of our new department and direction was to strengthen relationships with community members who are most in need of services but often are socially isolated or overlooked. It was also a strategic move partly informed by the library’s partnership with the Harwood Institute for Public Innovation (theharwoodinstitute.org).

The vision for our department was very simple: a model of engagement with an emphasis on community outreach and collaboration, as opposed to the former model of isolation and separation. This model has since grown and served the community well.

WHERE ARE WE NOW?

Nearly five years later, we have made significant strides using this community outreach and engagement model. We now have 23 staff, including our director of human services, trained in peace circle keeping, a key restorative practice. The intention in training this first cohort was to rely on the tools in various departments for programming and engagement with the public. But due to limitations posed by COVID-19, we were forced to close our doors and had to be creative in how we used this newly acquired tool. Recently trained staff focused on conducting virtual peace circles with staff to support them during COVID-19. This has proven to be beneficial and showed our organization that restorative practice, commonly used with teens, is beneficial to serving other populations, too. More recently, we’ve hired a restorative practices coordinator, Tatiana Swancy, who is responsible for “developing, implementing, and promoting practices and programs that support the library’s antiracist journey,” according to OPPL’s Manager of Adult Services Alexandra Skinner. In her new role, Swancy will deploy her peace circle skills to further promote our model of community outreach and engagement, which includes creating spaces where the stories and experiences of community members who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) can be shared and received.

Over the last three years, OPPL has hosted an annual Restorative Justice Conference, promoted through the community of practice RJ & RP in Public Libraries, on the library’s YouTube channel and promtional material, social media, and other media platforms; open to anyone with an interest in learning more about restorative justice and practices, it continues to increase in attendance each year. The theme of the most recent conference was “The Medicine Wheel: Balancing Humanity,” in response to the unprecedented challenges faced by our communities in 2020. The theme drew from the medicine wheel’s use as an ancient healing method of acknowledging the balance of the four components of humanity: mental, spiritual, emotional, and physical. The conference website quotes physician Louis T. Montour, Mohawk of the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy, who wrote, “In Native American language, ‘medicine’ meant power, a vital energy force that was within all forms of nature. It also meant ‘knowledge’ because knowing gave the ‘knower’ power to do, to achieve, and to attain.”

The conference explored the nature of restorative justice and invited attendees to engage in various restorative practices. We focused on building community and partnerships, addressing important social justice topics, and educating ourselves on ways to best show up for one another and continue to learn about the evolving field of restorative justice. This past year we also moved our annual conference to a virtual platform. Despite switching our structure from a weekend to a monthlong experience, we hosted more than 41 workshops and had nearly 400 logins from attendees all across the nation. The feedback we received was overwhelmingly positive. The 2021 conference will have a portion focused specifically on libraries.

|

EQUITABLE PRACTICES Left: waiting for community court in SPL’s downtown library. The Tap In Center at SLCL provides advocacy services. Left photo courtesy of Spokane Public Library; right photo courtesy of St. Louis County Library |

10 Practical Steps for Integrating Restorative Practices in Libraries

Here are 10 key components to consider when integrating restorative practices in public libraries, together with examples and advice from a variety of U.S. public libraries that are implementing these practices.

1. Ensure mission alignment. Any initiative your organization takes should be in alignment with the mission, vision, and values of the organization. Mission alignment gives the community an answer to the ‘why are we doing this?’ question that is asked when any change or initiative is implemented. “The easiest way is to tie your mission to the work [even though] it may look different from what you were doing two years ago,” says Andrew Chanse, executive director at Washington’s Spokane Public Library (SPL), when questioned on how SPL successfully integrated restorative practices. Chanse, who was hired as a “change agent,” expressed trepidation when local judge Mary Logan proposed a partnership between Spokane County Court and the library. He recalls, “I quickly went from ‘Hell no!’ to ‘Hell yes!’ ” when he recognized the potential impact such a collaboration would have on the community. The community court housed in SPL adjudicates quality of life crimes such as vagrancy, loitering, disorderly conduct, and begging in the downtown corridor of Spokane using restorative practices and justice. Since 2013, the partners have served more than 1,300 individuals, taking a proactive approach to aid them in gaining access to social services such as housing, employment, mental health counseling, getting appropriate IDs, and signing up for social security.

2. Utilize assessment. This preliminary step is essential to implementation of restorative justice within any organization. An awareness of the work that has been done, what has or hasn’t worked, and why will aid in identifying where best to implement restorative practices. Some institutions may very well be utilizing restorative practices without identifying them as such. If the foundation is there, that’s often a great place to start! An assessment also gives light to the perspectives of the staff within the organization about how integrating such practices may impact their work, as well as the reservations and hesitancy they might have.

3. Train staff. “When I was interviewing librarians and library staff, I noticed a real difference between people who came in with a restorative justice background and the people who were learning it,” recalls SFPL’s Austin, who works with jail and reentry services. Austin further notes, “There’s a difference between culture and practice. The people who come in with a restorative background use a lens that ‘everything is restorative justice,’ and the people who were learning it [said that] this is a ‘toolset that I implement.’” It is imperative for a successful implementation of restorative practices that organizations take time to invest in the education and training of staff about what restorative justice is and how restorative practices can be incorporated, and the implications those practices may have on the staff. Restorative justice philosophy emphasizes every voice being heard and the power of consensus, which is the process of obtaining agreement within a community. Consensus is a necessary component for any of these practices to work.

4. Ask restorative questions. Restorative questions are used to process incidents of harm. Whether within the organization or with the public, restorative questions can be helpful in addressing conflicts. Such questions include: What happened? Who was harmed? Why did it happen? What could have been done to mitigate it? How can this be made right? Restorative questions highlight the following:

- individual(s) who experienced the harm having a voice in making things right;

- individual(s) responsible for perpetuating the harm taking responsibility;

- promotion of active listening;

- participation of the community.

5. Say “yes” and figure out the rest later. This particular step specifically targets those at a decision-making level within their organization. Both Chanse and Kristen Sorth, executive director of St. Louis County Library (SLCL), MO, spoke to the habit and power of saying “yes” and being receptive when approached with opportunities to integrate restorative practices and initiatives from staff, and then working through the details. One such “yes” is SLCL’s Tap In Center, which provides services for individuals in need of advocacy for issues such as status updates on court cases, warrant resolution, or general legal counsel. This program is run in partnership with several community stakeholders, including the Missouri State Public Defender’s Office, Bail Project, MacArthur Foundation Safety and Justice Challenge, University of Missouri–St. Louis, St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office, and St. Louis County Department of Justice Services.

6. Pilot it. Piloting is a nonthreatening way to research the viability of a specific initiative within your organization. Many libraries that have restorative justice integrated into their systems started with the teen department. Pima County Public Library (PCPL), AZ, Branch Manager Em Lane says, “Restorative practices aided in ending the ‘us versus them’ dynamic that existed with teens/tweens and staff.” PCPL was one of three libraries that received the Urban Libraries Council’s 2017 Top Innovator award for its Restorative Practices for Youth Program. It was initiated as a pilot to address the impact of expelling and suspending youth from the formative institutions in their lives. When data was collected and analyzed, it yielded a reduction in incidents and issues. Once you produce the data, “inundate staff and administration with information,” Lane advises. He has worked his way from associate to branch manager, spanning five of the 27 libraries in the PCPL system, and at each post he has implemented restorative practices.

7. Start with teens. An overwhelming majority of the organizations I spoke with about restorative practices indicated that their work started with teens. Nationally the teen population within public libraries present similar challenges: defying rules, talking loudly, taking up space, challenging authority, and even moodiness. A restorative approach takes into account the human development of the teen demographic. Erin Bogle of Hennepin County Library (HCL), MN, emphasizes “the emotional toll removing a youth and enforcing punitive rules can take on staff.” Bogle suggests “a conversation with youth, as opposed to strict enforcement of rules, which often leads to escalated conflict and tension,” as a restorative approach that leads to more positive outcomes. “We ask staff participating in Restorative Justice training to think about a time they changed their own behavior. What helped? What didn’t help? We’ve heard being shamed or people forcing change doesn’t stick, and that change happens when people have access to resources they need, people supporting them, and the right information to center the change in values that mattered to them.” Bogle notes that HCL has supported the implementation of restorative tools such as peace kits, restorative justice chats/conferences, and situation debriefing, all of which promote “I” statements, active listening, and accountability.

8. Create a welcoming environment. We see the “libraries are for everyone” campaigns, but what are we doing to make sure everyone feels welcome? One of the first steps is recognizing the importance of relationships and centering them on engagement. This creates a restorative and welcoming atmosphere for library patrons. At OPPL, every school day at 3 p.m., the teen services staff welcomes not only teens, but every patron who enters the space. Patrons become accustomed to the greeting, and staff mebers get to know the names of the teens as they walk in. This creates a sense of belonging that is a key component of building relationships.

9. Join or create a community of practice. The Harwood Institute has a term, “turning outward.” This is the foundational outreach. There are people out there who are either doing or want to do some of the same things as you. Intentionally find and build relationships with them. I created a community of practice shortly after I started working in libraries. I felt isolated and needed other perspectives to guide my work. RJ & RP in Public Libraries still meets—currently on Zoom—on the last Friday of each month to discuss restorative practices in public library spaces.

10. Build a team with staff and community partners. Radical changes require you to “be long-term radical, short-term pragmatic,” says Lane. This may entail working with community partners who have mission alignment with your initiative. During the piloting stage at HCL, staff conducted environmental scanning and collaborated with others already doing the work: PCPL; Oakland County Library, MI; Skokie Public Library, IL; Minnesota Department of Education; Minneapolis Public Schools; and colleagues within other Hennepin County departments.

Restorative justice and practices are relatively young in the field of social sciences, but very commonly practiced and rooted in centuries of Indigenous culture. There is a lot that is known, and simultaneously there much more we are continuing to learn about this work. We do know that restorative justice and practices are transformational in creating change within organizations, institutions, and communities.

Stephen Jackson is Manager of Teen Services, Oak Park Public Library, IL.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!