Measuring Diversity in the Collection

In the same way that fitness trackers offer reality checks for sedentary lifestyles, diversity audits cast light on the homogeneity embedded within library collections, providing data that identifies gaps in representations of race, gender, sexual orientation, ability, and other traditionally marginalized perspectives.

|

REPRESENTATION MATTERS Enthralling kids at the Skokie PL story time.

|

A collection diversity audit is a crucial tool for libraries to assess their offerings. Starting small makes it manageable.

“You manage what you measure” is an adage embraced by business schools and self-help gurus alike. The sentiment also applies to library staff looking to assess the inclusivity of collections and programs thorough diversity audits. In the same way that fitness trackers offer reality checks for sedentary lifestyles, diversity audits cast light on the homogeneity embedded within library collections, providing data that identifies gaps in representations of race, gender, sexual orientation, ability, and other traditionally marginalized perspectives.

Armed with this information, librarians can more mindfully work to narrow the gaps. According to LJ’s 2019 Public Library Diverse Materials Survey, only nine percent of responding libraries have conducted a collection diversity audit, while another 14 percent plan to run one in the future. A common obstacle is the difficulty of developing a methodology that fits within already heavy workloads. In 2017, the Skokie Public Library (SPL), IL, embarked on a two-year audit designed to cultivate insights without overwhelming staff.

SETTING THE SCALE

Our audit at SPL stemmed from a strategic initiative “to ensure adequate representation of different groups and cultures and to foster equitable access to learning and leisure materials.” This objective was at once deeply worthy and inherently confounding—with more than 450,000 physical items in the collection, determining “adequate representation” seemed impossible.

After our research failed to identify any libraries that had taken on such an enormous audit to use as a model, we decided to narrow our focus to collections used in three high-profile areas: youth story times, adult film screenings, and adult book discussions. These programs are popular, heavily marketed, and draw significant levels of community engagement, so it seemed crucial to discover to what extent they showcased diverse works. Practically speaking, this also meant we would only need to survey a few hundred titles rather than a few hundred thousand.

We further limited ourselves to analyzing a one-year period of screenings and discussions and half of the story times at SPL. These uneven parameters were set because we had not previously tracked story time books and did not wish to wait a full year to compile the results. We also knew there would be many more story time books to log than films or book discussion titles and wanted to be realistic about the number of staff hours absorbed by the project. A clearly defined, manageable scope took the project from an impossibility to one that could be completed in a few months.

DEVELOPING A METHODOLOGY

Next came deciding which data points to track. Each book and film would individually be assessed to determine whether it reflected a measure of diversity in the identity of either its main characters and/or its author or director. In the interest of not reinventing the wheel, we reached out to the University of Wisconsin’s Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) to share the rubric used in its much-heralded diversity assessments of youth books. Because the CCBC analysis focuses only on race, we talked about how to widen our lens to consider other underrepresented groups. After some discussion, we settled on tracking the following categories:

- Multicultural

(diverse set of characters with no primary protagonist) - White

- Biracial

- African American

- Asian Pacific

- First Nations

(First/Native Nations/Indigenous) - Latino

- Middle Eastern

- Disability

- LGBTQ+

- International (white)

(Not U.S. or Canadian, but white) - International

(Not U.S. or Canadian, but racially or ethnically diverse)

Two other options were included: “unknown” for when we couldn’t find the necessary information, and “animal/other” for works that featured a nonhuman protagonist such as a bear or a crayon (a common phenomenon in story time selections).

With the “what” decided, it came time to tackle the “how.” The auditing was divvied up among four staffers (two working on story times and two tackling films and book discussions, respectively). Although many audits are tracked via spreadsheet, we had so many categories and contributors that we found it easier to create a simple Google Forms survey for each program. Three were created, with each title meriting a separate entry. Staff logged the title and then selected a category for the work’s protagonist and author/illustrator/director. More than one category could be chosen, and there was space to indicate whether more discussion would be required. Once done, all the information could be exported to a spreadsheet for easy filtering, analysis, and graphic visualization.

Approaches varied in researching each title. In some cases, the staffer was familiar with the material and could fill out the form in under 30 seconds without having to see the item. (It doesn’t take much for a youth fiction expert to remember that I Am a Tyrannosaurus is about…a tyrannosaurus.) Other books and films demanded deeper dives. To determine appropriate categories, we tracked down the materials to assess them in person; looked to biographies on publisher and author websites; read author and director Q&As; and referenced critic’s reviews. We decided that we wouldn’t spend more than seven to eight minutes researching a person or work. If the information was not evident, we’d mark it as “unknown.” We also spent time hashing out areas of ambiguity. One conversation concerned a film starring an actor who identified as bisexual but was playing a straight character. Should this put the movie character in the LGBTQ+ category? (We ultimately decided that it did not.)

As the previous example suggests, this process was at times confusing and even uncomfortable. It’s awkward and a bit unsettling to be actively looking for details on someone’s race or gender, not to mention that the entire exercise was naturally subjective, susceptible to user bias and errors (we didn’t have time for a second person to double-check each entry). Nonetheless, we reasoned that a flawed audit would still be better than no audit at all.

RESULTS ARE ONLY THE BEGINNING

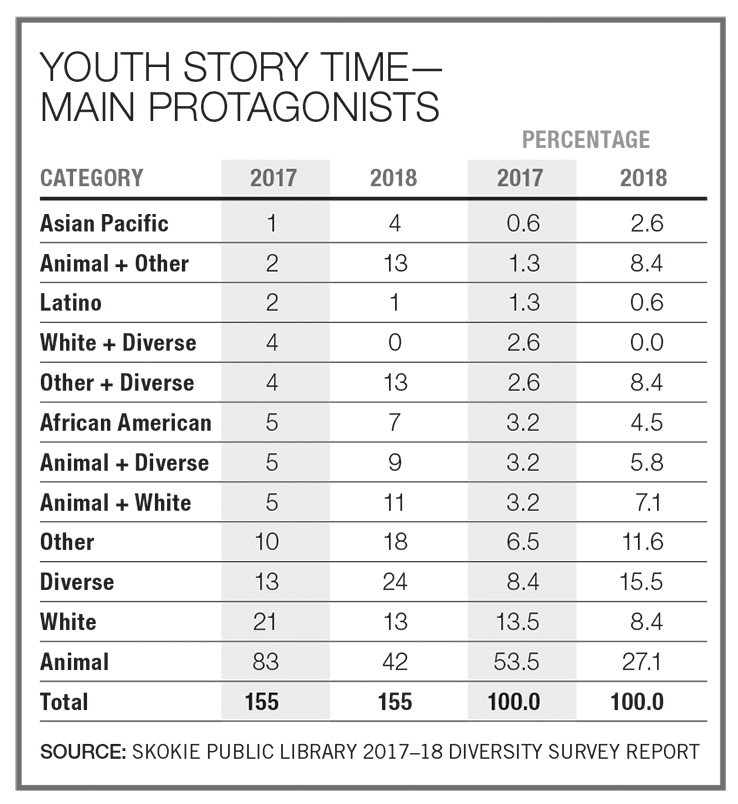

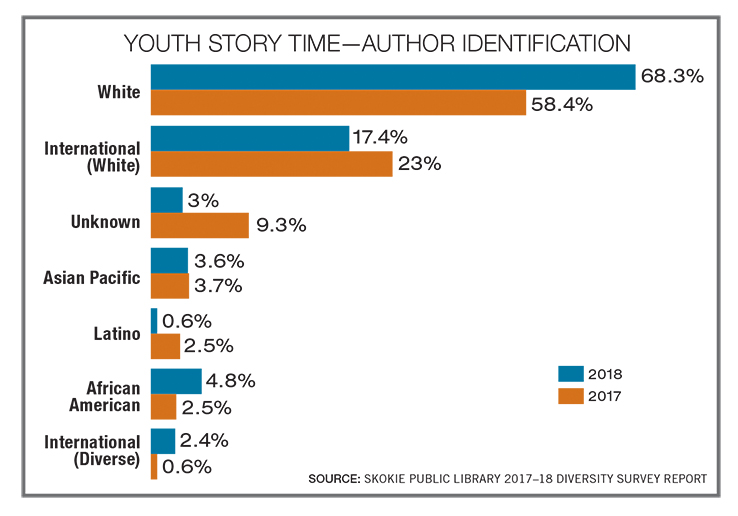

When the dust settled, we’d tracked 156 kids’ books, 79 movies, and 48 book discussion selections. All in all, the results were promising. We learned that of the story time books centered on human characters, 60 percent had some measure of diversity. Meanwhile, 42 percent of film protagonists were diverse, including four films featuring main characters with disabilities. Thirty-four percent of book discussion titles were written from an #OwnVoices perspective. On the other hand, we also saw we hadn’t included many titles from a Middle East or First Nations perspective and that the vast majority of the films we screened were directed by white men.

Once we knew what we had, we had to decide what we wanted, by setting collection diversity goals or benchmarks. Each library will have different criteria for its diversity goals, whether they are tied to local demographics, strategic initiatives, or other considerations. On the heels of a diversity audit at the Naperville Public Library (NPL), IL, plans are under way to use patron-driven acquisition to identify collection areas commanding more diverse representation (and potentially to redistribute budgets). The library also looks to increase the exposure of diverse materials by carefully curating weeding. “Weeding can help make room on your shelves for diverse materials and also enhance the visibility of the diverse books you already have,” says Karen Toonen, a collection development librarian at NPL. “At the same time, when a diverse title shows up on the weeding list, I’ll give it a second chance by putting it front-facing on the shelf or in a display.”

At SPL, we simply sought to see some measurable improvement above the initial baseline. In the year following the audit, we encouraged colleagues to integrate diverse materials into their programs via several strategies. First, we shared and discussed the audit results to raise staff awareness and to discuss diversity within the framework of the myriad other considerations used when selecting materials for programs. We added Kanopy to our digital offerings—the platform’s blanket public performance rights allowed us to increase the base of diverse films available for screening beyond what was available through other licensing services. The collection development librarian overseeing youth fiction began sending a monthly email to youth services staff that highlighted diverse titles concentrating on popular story time themes. Readers’ advisory (RA) staff created a best practices document for selecting book discussion titles that would uplift the voices and experiences of marginalized individuals, and staff ensured that at least one of each month’s multiple discussion groups read a diverse title.

Then we conducted another audit to see if any of our efforts had moved the needle. The second-year survey indicated that we had indeed made strides. Books with human protagonists were read more frequently in story times and more often highlighted diverse characters. The percentage of diverse protagonists increased by nine percent in book discussion titles and inched up six percent for screened films. While not earth-shattering, the results pointed to progress and validated anecdotal evidence that our staff were becoming increasingly sensitive to opportunities to showcase diversity. As the library moves toward a large-scale renovation in 2020, we are talking about ways we can integrate the auditing process into a revised collection development plan that sets firmer guidelines for expanding materials diversity.

CUSTOMIZING THE PROCESS

When first considering diversity audits, most administrators and librarians on the hunt for a quick and simple methodology are disappointed to learn that audits are such painstaking, manual work. With small collections, a more comprehensive survey is possible—Karen Jensen of the Fort Worth Public Library (FWPL), TX, created an invaluable guide to executing a YA collection diversity audit on School Library Journal’s Teen Librarian’s Toolbox blog (). However, when collections are larger and/or staff time is scarce, it’s important to understand that diversity audits can be applied in a multitude of bite-size ways. For example, an SPL staffer began independently auditing the books recommended by staff in our form-based RA service, using our original framework but customizing her survey by adding categories. Meanwhile, our fiction selector works with a spreadsheet to track the titles on a popular display. Diverse reads are highlighted in a different color—at one glance the document reveals whether the display is getting too homogeneous.

Collection development or acquisitions staff can audit all the books purchased by the library in a monthlong window. Before clicking “purchase” on their order cart, ebook selectors can ask themselves, “Who isn’t represented here?” Marketing emails can be inspected to see that diverse titles are included every month. A diversity audit can focus on a particular area, such as indigenous populations or LGBTQ+ stories; they can be done by one person or structured to include multiple stakeholders such as teachers, patrons, and community leaders. The latter can be crucial in offsetting the lack of diversity in the library profession itself: if audits are conducted from a white, cisgender, able-bodied perspective, then biases connected to dominant power structures creep into the mix.

Diversity audits have other limitations. An audit does not erase the need for publishers to champion writers from marginalized groups, nor will it necessarily catch a book that features diversity but includes stereotypes or inaccuracies. This phenomenon gets called out frequently in youth materials, such as with Debbie Reese’s incisive book reviews on the American Indians in Children’s Literature blog. Such analysis could be integrated into an audit with additional research. When developing training on #OwnVoices authors, Jensen (a 2014 LJ Mover & Shaker) and her FWPL colleague Kathryn King do a web search of titles with the word controversy to help verify that they are not recommending titles that have been criticized for harmful representation. According to Jensen, at the very least libraries “have an obligation to make sure that we are not highlighting or promoting these works in any way because they contribute to a culture that is harmful to some of our patrons.”

When it comes to diversity audits we shouldn’t allow the perfect to be the enemy of the good. Any attempt to view library collections and programs through an equity lens is valuable, and any actionable data provides a foundation for developing strategies to diversify our libraries.

Annabelle Mortensen is Access Services Manager, Skokie Public Library, IL; a LibraryReads board member; and a former speaker for LJ’s Equity in Action course

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Teresa Lanford

A worthy endeavor, to be sure. It could definitely be a great deal of work, but very valuable in raising awareness among collection development staff & programmers. We need to serve ALL of our community members. Offering a better variety of materials & events will result in a more diverse population of library users.Posted : Jun 28, 2019 01:10