Circus Collections From the Big Top and Beyond | Archives Deep Dive

The Robert L. Parkinson Library & Research Center at the Circus World Museum in Baraboo, WI, and the Archives at the John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, FL, have extensive circus collections, from posters and programs to performers’ scrapbooks and diaries.

|

Adam Forepaugh & Sells Bros., Poster Collection, Lithograph,1900, created by Strobridge Litho Co. Captain Woodward's Seals: "Capt. Woodward Excells Himself With His New Trained Sea Lions etc."Courtesy of Circus World Museum |

For many, the circus evokes trapeze artists, clowns with red rubber noses, and top hat and tails–wearing ringmasters. For others, the circus highlights the cultural, social, and economic forces that shaped it, offering a window into the relationship between popular entertainment and all-too-common prejudices around race, disability, gender, and class.

While these performances and the complexity they represent may be fleeting moments—the curtain comes down, the tent lights turn off, and the circus moves on—the materials produced around them are not. The Robert L. Parkinson Library & Research Center at the Circus World Museum in Baraboo, WI, and the Archives at the John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, FL, have extensive circus collections, from posters and programs to performers’ scrapbooks and diaries.

These materials are great windows into the past, and can help users understand the cultural, social, and economic forces that shape the circus. Heidi Connor, chief archivist at the Ringling archives, explained that circuses were the most popular form of entertainment in the United States from the 19th to the 20th century. They had an economic impact on the towns they passed through, purchasing supplies to feed and maintain performers, workers, and animals, Connor said. Much can be understood through circus records, including the history of advertising and business.

Peter Shrake, archivist of the Circus World Museum library, said, “Circus history is also social history. You can use the circus as a lens to study the era in which [it] existed. There's a lot of things to talk about—race, gender, and technology.”

It’s important to note that while many know the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus as the “Greatest Show on Earth,” circuses have a violent history of racism and ableism, exploiting individuals from marginalized populations for financial gain. From the earliest days of founder P.T. Barnum’s shows, he displayed and abused Joice Heith, an enslaved African American woman, profiting from her both while she was alive and after her death. In a 2017 article in The Root, Kondwani Fidel describes how Barnum displayed “conjoined twins and people who suffered from elephantiasis, vitiligo, blindness and other anomalies, all of whom were Black…also perpetuating the idea of the medical racial inferiority of Black people.”

A WEALTH OF HISTORY AT CIRCUS WORLD

|

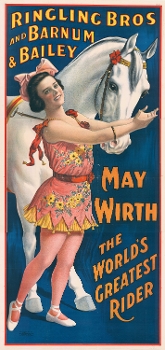

Ringling Bros. Barnum & Bailey created by Strobridge Litho Co., Poster Collection, Lithograph, 1920. Equestrian May Wirth stands beside a white horse.Courtesy of Circus World Museum |

The library at the Circus World Museum has one of the largest archives dedicated to the circus in the United States, and possibly the world. Materials date from 1793 to the present day, and include lithographic posters, manuscripts, the corporate archives of Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus and other circuses, recordings and oral histories, programs, and more. Shrake noted that the museum greatly expanded in the 1960s and 1970s under the direction of then Executive Director Chappie Fox—particularly with the addition of the corporate records, acquired by the museum in 1971. Shrake estimated that the collection contains at least 370,000 items, not including the 4,000 to 5,000 cubic feet of manuscript material and corporate archives. Overall, it holds material on about 2,800 American circuses.

The library opened in 1965, six years after the museum itself, to “manage and maintain the museum’s paper, image, and sound materials,” according to its website. Since the library was founded, the collection has grown with acquisitions from the Ringling and other circuses and family materials from performers and workers. The collection also holds artifacts such as the costumes of ringmaster Josiah May, circa 1855–56.

Shrake recalled one of his favorite pieces: A woman walked in with an old ledger that no one in her family wanted that turned out to be a business ledger–turned-scrapbook for the Ranee-Sorenson Shows, which Shrake described as “a kind of a hybrid between the traveling vaudeville and small circus show that was based out of Northwestern Wisconsin'' around World War I. The scrapbook contained everything from “business records, notes, and scrapbooks to photos, the entire synopsis of this tiny show all in one little ledger,” said Shrake. It may have originally come from someone in the Sorenson family.

Other items include a Philadelphia newspaper that advertises the Ricketts Circus, credited as one of the first circus performances in the United States. The archive features a wide variety of circus posters, such as an 1847 Raymond & Waring’s Menagerie poster, an early example of lithographic color usage.

The library receives between 1,500 and 2,000 inquiries worldwide a year, from scholars to genealogists. Shrake estimated that 85 percent of the research has been done remotely throughout his tenure at the library since he started in 2011; he suspects that the cost and time to get to rural Wisconsin might be a factor. Genealogists reach out to look for information about family members who may have worked in the circus. The archive has indexes of over 350,000 names of circus owners, performers, and workers.

Academics have used the collection in numerous ways. Shrake noted that the structure of the circus changed, broadly, from equestrian shows to circus tent shows in the 1820s. Later circuses merged with menageries, traveling by wagon and then trains in the mid-19th century. After World War I, they switched to trucks and, no longer limited by railroad routes, found new audiences. The Great Depression caused many shows to close, as did competition from radio, television, and movies, but the circus continues to evolve into the present day. “The circus is always looking for what's going on now,” Shrake said. Some circuses, notably Ringing Bros. and Barnum & Bailey, have pledged not to use animals in their performances.

Janet Davis, teaching professor at the University of Texas at Austin, used the collection to research her book The Circus Age: Culture and Society Under the American Big Top (2002); so did Sara Gruen for her novel Water for Elephants (2006). The Circus Historical Society researches the archive for its publication Bandwagon, as has PBS for the recent multipart series The Circus on American Experience. Shrake also noted that model builders, who make small replicas of towns and more, use the archive to deepen their hobby.

DOCUMENTING “THE GREATEST SHOW”

The Ringling Archive, in Sarasota, FL, takes its name from John Ringling, one of five brothers who owned the famous circus company. The museum—John and his wife Mable’s home until her death—was permanently opened to the public in 1932, but the archive was not established until 1989, when the institution received a National Historical Publications and Records Commission grant that provided initial funding.

In addition to circus materials, the archive also contains content related to the museum, the Ringling family papers, the era of “Wild West” shows, and more. Materials date from the 16th century to the present day, according to Connor. She estimated that the library holds 10 million items, with 10 percent of those being photographs and other visual content, such as a 1575 engraving of Anthoni Franck, the German “giant.”

Sarasota philanthropist Howard Tibbals expanded the collection with donations of circus-related materials in 1999, including an intricate three-quarter-inch-scale model of the tented Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus of the early 20th century, programs from the major circuses, posters, and more. “The breadth and depth of the Tibbals collection is what hallmarks it as a very important and essential resource for the study and interpretation of the importance and influence of circus, particularly in North America,” Connor said.

Other notable objects include moving images of different acts. “This is the quintessential record of entertainment history because moving images capture everything. The pauses, the action, the music, the crowd respond, the costumes, the lighting, it's all in there,” Connor explained. “All the still images in a row can never give you the action.” Many have been digitized and are available online .

The Ringing also holds the glass plate collection of photographer Frederick W. Glasier (1866-1950), who took photos of the circus. Glasier had that “ Henri Cartier-Bresson magic moment eye,” Connor said (Cartier-Bresson was a French photographer known for his street photography).

In conjunction with the Circus World Museum and the special collections at Illinois State University (ISU), the three institutions collaborated to digitize over 300 circus route books from all three collections that show the journeys circuses made from the 1840s through the 1960s. These are part of a digital exhibition currently on the ISU website titled Agency through Otherness: Portraits of Performers in Circus Route Books, 1875–1925.

Like the Circus World Museum library, the Ringling archive has been used by scholars and students in many disciplines. Gary S. Cross, emeritus professor of history at Pennsylvania State University, studied the materials on sideshows for his Freak Show Legacies: How the Cute, Camp and Creepy Shaped Modern Popular Culture (2021. The book, he told LJ, examines the ways that a modern audience shifted such exhibits away from the exploitation of vulnerable populations, and “came back with the 1960s counterculture [to] continue in new forms.” Janet Davis also used the collection for her book The Circus Age.

The Ringling also works with students from Ringling College of Art & Design and other educational institutions. In 2020, a student project looked to toys and materials in the archive to create an original circus character, with a full costume, backstory, and act. Not only did the archive provide inspiration for the project, but it broadened the students’ knowledge of how archives work and how research can be deepened through exploration of physical records beyond what is available online.

RACISM, ABLEISM, AND EXCLUSION IN THE CIRCUS

As noted earlier, while there is joy in the circus, it has a violent history of racism and exclusion of people of color and exploitation of people with disabilities. Various circus shows and related entertainments (such as sideshows and Wild West shows) used racist stereotypes and violence as well as non-consensual display of African American, Native American, disabled, and other marginalized people for entertainment.

For example, Shrake noted that 90 percent of the library’s Wild West materials predate the 1900s and are “representative of the era into which they were created,” and the Ringling does not censor them. These sources “are a reflection of the [certain] audiences which [the shows] strove to entertain,” he explained. Some shows were segregated in both the North and the South.

However, there is a growing body of scholarship on the experiences of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) circus performers and workers. Shrake noted the pioneering work of Dr. Sakina Hughes, associate professor of Ethnic Studies at Santa Clara University, CA, who has worked to center the stories of Black and Native American circus performers and workers.

In Hughes’s dissertation on the topic, she wrote: “Circus history has paid little attention to African American and American Indian laborers and performers’ daily lives or how they articulated their experiences within the industry.” Library Journal recently followed up with Hughes; she noted that American newspapers and magazines have featured Black contributions to the circus, including those of James Albert “Billboard” Jackson (1878–1960), who “was named the first African American editor of the Negro Department of Billboard magazine” according to historian Delores C. Phillips. Jackson wrote extensively about Black entertainment, including the circus.

Hughes also mentioned Coy Herndon, who died in 1939—a circus performer, and journalist for the Chicago Defender who wrote the column “Coy Cogitates,” which provided a “treasure trove of what is it like to be a Black performer,” said Hughes.

One of Herndon’s articles called out the Ringling circus for putting posters up over Black circus posters. As a result, Ringling responded with a letter of apology, which Herndon published. “He really does reflect on the role of a Black performers, Black artists in the circus,” Hughes noted. “He says: Life is [hard] for us and as circus performers, our job is to create a space where people can just forget for a couple of hours.”

Hughes has also been researching the voices of women, such as Blues singers Ma Rainey (1886–1939) and Lizzie Miles (1895–1963), as well as Native American women who were on the lecture circuit advocating for their tribes and nations to combat the demeaning depiction of Native women in “Wild West” Shows. “The circus is a microcosm of America,” she explained, “because even in the circus you see this spirit of resistance."

Hughes noted the efforts of Veronica Blair, circus performer and founder of the Uncle Junior Project, a “community-driven documentary series that gives people the opportunity to learn, celebrate, and take pride in the inspiring history of Blacks in the American circus.”

In 2020, Hughes attended virtual conference “From the Sideshow to the Center Ring,” Body Identity: Presence, Performance, and Politics, a Conversation for Aerial and Circus Artists of Color,” where she spoke about “the history of Black people of various professions and arts who were in the American circus throughout history.”

Thanks to the work of historians such as Hughes and Blair, as well as the ongoing collecting efforts of circus archives, the full picture of American circus culture continues to grow. Both the Circus World Museum library and the Ringling archives are open to researchers. While the museum is closed during the fall and winter months, Shrake said, the library is open year round. People who wish to access the collections should contact Shrake via email or fill out an inquiry form for Connor. Both collections are currently working to provide online guides, the archivists can offer a fuller picture of what is available.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!