Inspecting American Medicine with the Historical Medical Library | Archives Deep Dive

The Mütter Museum’s less famous upstairs is equally fascinating—and it’s now open to non–medical professionals without an appointment. The library, an independent collection of books and ephemera related to the “history of medicine and medical humanities,” according to its mission statement, recently announced that it is now open to the public on weekends, included in the price of admission for the Mütter.

|

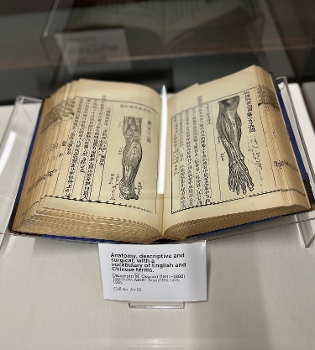

Anatomy book with vocabulary of Chinese and English terms, 1881Image courtesy of the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia |

Many people may be familiar with Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum, founded in 1863 when Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter donated his teaching collection of medical anomalies to the Philadelphia College of Physicians.

The Mütter has drawn scrutiny for the ethics of its displays of human remains, including the need to better address questions of consent and the acquisition of “collected” bodies, some of which were acquired without consent owing to racist practices; the use of period-accurate labels without modern context to address the use of slurs; and issues around ableism and how the divergent bodies on display are presented. The museum has made efforts to deal with these matters, such as updating label information and working with disability consultants, but concerns are ongoing. Still, the “disturbingly informative” Mütter—as per its slogan—attracts visitors from around the world.

The Mütter’s less famous upstairs is equally fascinating—and it’s now open to non–medical professionals without an appointment. The library, an independent collection of books and ephemera related to the “history of medicine and medical humanities,” according to its mission statement, recently announced that it is now open to the public on weekends, included in the price of admission for the Mütter Museum.

The move to open the library on the weekends started as a carpet replacement project, explained Heidi Nance, director of the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The carpet was in bad shape and of unknown age. Replacing it led to repainting the walls and eventually a full renovation of the library and the decision to invite the public in.

Both the Mütter Museum and the Historical Medical Library are part of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, a private medical society founded in 1787 by prominent local physicians, including several founding fathers, such as Benjamin Rush, Nance said. The library was founded a year later as one of the earliest—if not the first—medical libraries in the United States.

Dr. John Morgan, one of the founding fellows of the College of Physicians, as well as a founder and professor at the medical school at the University of Pennsylvania, started the collection with a donation of five books from his personal collection. Since then, the library has grown through donations from fellows’ and local physicians’ libraries and private collections. Nance described it as “a library of libraries.”

|

Interior of Historical Medical LibraryImage courtesy of the Historical Medical Library at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia |

The Historical Medical Library also contains a significant number of medical journals, which offered students and other medical professionals access to research in the mid–20th century. But as access to these journals became more widespread, as well as available digitally, decades later, the Historical Medical Library began to focus on its unique strengths and areas of adjacency, Nance said.

For example, earlier this year a visiting scholar from the School of Humanities at Liverpool Hope University, UK, interested in the intersection of nutrition and aviation—focusing on astronauts, food, and health—used the library’s Journal of Aviation Medicine, published from 1930 to 1959. These journals are not commonly collected, and the library may have one of the most complete collections known. Since the library also houses many foreign language dissertations, the scholar found a Russian dissertation on aviation and nutrition, along with other materials to support their research. “That really amplified the value of the individual items,” Nance said.

The Historical Medical Library is composed of special and archival collections, Nance explained. The special collections contain rare information related to the American practice and understanding of medicine. Specialties range from anatomy and public health to yellow fever, in a variety of formats that include advertisements, lantern slides, pamphlets, medical photographs, and more. The collection also holds about 400 incunables—books printed before 1500—as well as books with moving parts that helped teach anatomy and other sciences. The archives contain the papers from medical professionals and organizations, as well as the papers of the College.

Large, high-resolution photographs from the library’s books, including images of plants and herbs, are on display on the walls. The College also houses the Benjamin Rush Medicinal Plant Garden.

Nance estimated that the library may contain 300,000 to 400,000 items between the special collections and archives; they span about 51,000 linear feet.

The collection has been used by a variety of researchers, including medical history students, artists, genealogists, and researchers of printing history, photography, and even architecture, as the building dates back to 1908. An American living in Norway once asked for the rights to a caricature in the library’s vaccination collection to use on an embroidery panel for an exhibition.

Previously, only researchers with appointments had access to the library during the week. Its opening is part of an effort to expand access to its rich but noncirculating holdings, explained Nance. The newly refurbished library has 12 new display cases for monthly pop-up exhibits using items from the collection.

Nance saw an opportunity to open the space up on weekends when fellows, staff, and researchers were not using the space. “It was just sitting there empty, and people were coming to visit the museum right downstairs. It seems like a really logical and comparatively easy move to make.” The library is currently open for visitors on the weekends. Nance hopes to provide a touch table that visitors will be able to use to explore the materials and their functions.

Nance considers the materiality and legacy of each item: “How many librarians and curators and owners have worked so hard over many decades to take care of this book…to ensure that it survived and in the condition it does.” Her team is “part of a long line of succession who are charged to store these items, so that hopefully 100 years from now, [the collection] will still be in the same condition.”

The library also houses items from the harmful side of medical history, documenting inherent prejudices within the practice of medicine, including at least five confirmed anthropodermic books made from human skin. Doctors who commissioned these books had them bound with the skin of patients who had died, commonly women from impoverished circumstances, and most often without the previous consent of the patient or their families. The Anthropodermic Book Project is working to test books alleged to be made from human skin. Of the 31 so far tested, 18 were confirmed as human (as of 2019).

While some institutions do not like discussing these items, the Historical Medical Library intends to be frank about them and not try to hide these problematic medical practices. “I want to treat the skin with the same level of reverence that I would for any other human, alive or dead,” Nance explained. There’s a debate in library circles about what to do with these books, such as finding living relatives to whom they can return the remains, or burying them. Nance said the institution has decided not to display them for the foreseeable future until the team can find a way to do so respectfully.

For people who want to read about this troubling practice and its relationship to medical history, see Megan Rosenbloom’s Dark Archives: A Librarian’s Investigation Into the Science and History of Books Bound in Human Skin, which talks about the books in the collection as well as others in the United States and the UK.

Anthropodermic books are not the only difficult items in the Historical Medical Library. Since the library contains the private collections of mostly white male physicians and other medical professionals, much of the material reflects the biases of their original owners. The collection holds items that originate in racist—and not scientifically accurate—medical beliefs such as eugenics, including books such as Leonard Darwin’s What is Eugenics? (1929) and Blanche Eames’s Principles of Eugenics: A Practical Treatise (1914).

But while it may be difficult to handle these materials, “there’s legitimate research that has to be done and people need to see them,” Nance said.

Nance also noted that the library does not hold much material from physicians of color; the early members of the college were white physicians who gave their papers to the collection. (In the early days of American medical schools, most did not admit Black physicians, so fewer formally qualified Black physicians were available to donate material. Dr. David Jones Peck was the first Black student to graduate from a medical school in the United States, in 1847.)

Among the few BIPOC healthcare professionals whose work is represented in the collection are Suzie King Taylor, the first Black nurse in the Civil War and author of a wartime memoir; Cuban doctor Carlos Juan Finlay, who determined that mosquitos spread yellow fever; Argentine doctor Bernardo A. Houssay, who won a Nobel prize in Medicine in 1947; and more recently, doctor Eliza Lo Chin, who published This Side of Doctoring: Reflections of Women In Medicine in 2002. Thus far, Nance noted that “we intend to prioritize the acquisition of materials created by physicians of color in the future.”

While white women also faced discrimination in trying to practice medicine, they are better represented in the collection, especially in materials related to gynecology and women’s health. Holdings include accounts from women who performed underground abortions, as well as the papers of female doctors documenting their experiences and work and encouraging women to join the field.

Overall, Nance said, “one of the ways we understand the present is through the lens of the past.” For example, Nance sees many parallels to the present day in the collection’s pro- and anti-vaccine materials. Many of the objections to vaccines in the past are the same as those made today, she said, “because human nature hasn't changed.” Examining how these issues were dealt with can help better inform and educate the profession in the future.

The library is open to all researchers, who can make appointments online. Non-researchers who are interested in seeing the library can visit from 10 to 3 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!