How to Build a Database

Digitizing, organizing, and contextualizing primary sources from libraries and archives presents unique challenges and rich opportunities.

Online databases have transformed the ways researchers use materials, in particular primary sources. Publishers’ approaches to gathering and organizing online collections are diverse, but all require forming relationships with libraries and archives and considering how researchers use their platforms. LJ spoke to several publishers about how recent database projects came to fruition.

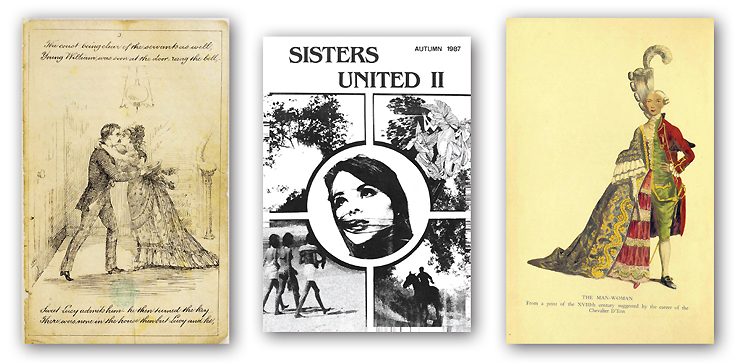

GALE ARCHIVES OF SEXUALITY AND GENDER

The Gale Archives of Sexuality and Gender present millions of documents that reflect LGBTQ history and the history of research into sex, sexuality, and gender. Documents have been sourced from numerous libraries and archives, including the New York Public Library, the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives, and the Lesbian Herstory Educational Foundation. The latest addition to the archives, Sex and Sexuality in the 16th Through 20th Centuries, is an expansive collection of books, monographs, and manuscripts, many of which were previously unavailable for public view. From conception to quality control, the development of the latest addition to the Archives of Sexuality and Gender has been going on for the better part of two years.

According to Phil Virta, acquisitions editor of the Archives of Sexuality and Gender, coming up with an idea for a database that resonates with customers is just one element. Identifying potential institutions and archival collections to populate it is important, too, he says. “It involves a lot of creativity, because you really want to find something that tells a story.” Editors must identify more material than they need, since “not every one of them is going to come through and sign an agreement. What comes through is what actually builds the archive.”

Gale had already formed a relationship and developed a collection with the Kinsey Institute, known for decades as the leading research institution on human sexuality and relationships. Virta knew the Kinsey Institute collection should be the basis of the latest archive installment, and so pursued other collections that would be complementary: the New York Academy of Medicine’s collection of rare and unique books on gender, sex, and sexuality, and the British Library Private Case Collection, consisting of books removed from the library’s public collection on grounds of obscenity.

There are more than 5,000 books in the resulting collection: 2,500 from the British Library, around 1,500 from the New York Academy of Medicine, and about 1,000 from the Kinsey Institute. None of these materials were previously digitized or widely accessible to scholars.

“In general, the collections I work with are hard-bound paper, periodicals, magazines,” says Virta.

Virta notes that “librarians and archivists shape projects like Archives of Sexuality and Gender by identifying the collections that are most consulted at their institutions, or that have the most research impact. I rely on the knowledge and expertise of librarians and archivists to help me select collections that are the best representatives of a particular subject or theme.”

For instance, Donald McLeod, head of book and serials acquisitions at the University of Toronto Libraries, who was part of the advisory board of the Archives of Sexuality and Gender from 2015 to 2019, encouraged Gale to include more international content, in particular from a Canadian archive, to make the collection “a much more wide-ranging and useful product for scholars.”

Bringing together diverse collections means that the process for bringing each institution’s materials onto the Gale platform will be different. Says Seth Cayley, vice president of Gale Primary Sources, “We see ourselves as partners with these institutions—we talk to the libraries about their needs, and how physical objects are going to be treated after digitization. Digitization often creates a lot of interest in patrons seeing the physical objects.”

For example, the Searchlight Archive at the University of Northampton, a partner in Gale’s Political Extremism collection, posted on Twitter that the archive had “seen a big increase in overseas usage this year, perhaps in part due to that exposure we got” from digitization. Cayley notes that such a surge in interest can be “a double-edged sword if a library isn’t equipped to deal with it.” He adds, “In some libraries, digitization is the reason for them to take something off shelves, if it is too delicate.”

After an agreement that works for both Gale and the materials’ home institution is finalized, the next step is to arrange a schedule with a scanning or digitization vendor. Gale scans on site in some cases, and ships materials off site in others. Scans go to another party for quality assurance. Next, the Gale content team ensures that metadata is applied. The final result has a similar look and feel to other Gale Primary Sources archives so that researchers will be confident in searching across archives.

BLOOMSBURY FASHION CENTRAL

Bloomsbury’s situation in creating Bloomsbury Fashion Central was different because the content it was combining was its own, not held in an academic library’s collection. The company acquired and combined four products: Berg Fashion Library, the Fashion Photography Archive, Fairchild Books Library, and Bloomsbury Fashion Business Cases. After purchasing Fairchild Books (an industry leader in fashion and design) and the Fashion Photography Archive, the publisher had material “covering virtually the entire spectrum of scholarship in fashion,” says Kevin Ohe, director of Academic Publishing for Digital Resources. It was a natural evolution to use those resources to create something digital, he says, “bringing all of our various fashion content together onto a single platform, indexing it across a single taxonomy…creating something that is larger than four databases.”

With the content already in hand and a vision for a comprehensive fashion platform, Bloomsbury’s major challenge was working with technology vendors to develop the database, as well as an e-commerce platform for Fairchild Books.

“We had to educate the software developer in what we do, and explain the usage of it to them,” says Director of Product Management Matt Kibble. In the earliest phases of developing Fashion Central, Bloomsbury created a plan for how the platform should appear and had vendors pitch for the work. Kathryn Earle, managing director for Bloomsbury Digital Resources, notes that planning and providing as much detail as possible are crucial when working with a third-party developer, because there are “lots of downstream cost implications if something goes wrong.”

In addition, vendor goals may not always perfectly align with publisher goals. Earle notes that technology vendors may aim to “quickly get something out of the door that meets minimum expectations,” while the publisher wishes to develop “the best possible product, even if it requires more work.” Since the project’s original development, Bloomsbury has made an effort to bring more development in house, to streamline the process.

In many ways, the creation of Fashion Central broke new ground for the company, as it was the publisher’s first major foray into placing digitized versions of its materials into a comprehensive database. “We’re trying to reinvent ourselves,” says Earle. “Our background is really in book publishing, [which] is quite straightforward and linear. With digital, you’re always having to think in 3-D, and reprogramming yourself to think in a different way, which is a challenge.”

Kibble added that, “A book goes out, and until the second edition you can forget about it. A subscription database needs new content and attention and fixes.”

Left photo ©Lacma; center photo ©Niall McIerney, Bloomsbury Publishing, PLC; right photo ©Fashion Museum, Bath

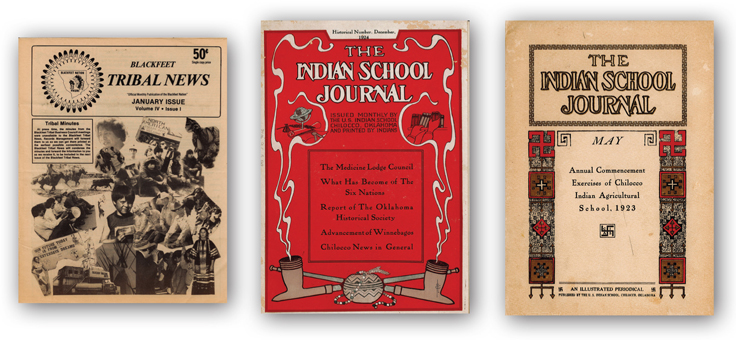

AMERICAN INDIAN NEWSPAPERS AND SERVICE NEWSPAPERS OF WWII

Relationships with archives and libraries are key for the team working on archival databases with Adam Matthew Digital as well. Two collections—the American Indian Newspapers and the Service Newspapers of WWII—showcase the ways that the publisher has brought unique primary sources to light. The American Indian Newspapers collection compiles publications from communities across the United States and Canada, published from 1828 to 2016. The Service Newspapers collection presents a range of wartime publications, from numerous nations and theaters of war.

With both collections, Adam Matthew Digital began with newspapers that had “as complete runs as possible,” according to Louise Hemmings, senior publisher with Adam Matthew Digital. The publisher’s relationship with the Sequoyah National Research Center at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock—the leading repository for these newspapers—shaped the development of the American Indian Newspapers, which was also supplemented with materials from the Newberry Library in Chicago.

According to Erin Fehr, an archivist with Sequoyah, the greatest benefit of this collaboration was exposing more resources to a wider audience and making the collections available to researchers—something Sequoyah couldn’t do on its own because of limited staff time and money. Fehr has used the digitized collections herself to answer research queries that would have previously required time-consuming research in print.

The company decided to create the Service Newspapers collection after learning about scholarly interest in wartime journalism. Their key partners for this collection were the British Library and the Imperial War Museum.

Any professional who has worked with archival newspapers knows that these materials can be quite delicate. The Adam Matthew Digital approach to digitizing materials involves visiting the archives and taking detailed accounts and assessments of materials. Some archives prefer to digitize their collections themselves, while for other projects, the publisher will work with a separate scanning vendor.

For the newspaper collections, Hemmings says that the publisher “hit challenges in terms of conservation to make sure they were stable enough to be digitized” and to identify “what might need treatment.” Close collaboration with the archives tied in with the projects’ mission to preserve digital copies and safeguard archival collections. From there, a project management team at Adam Matthew Digital oversaw all aspects of the digitization process, including quality checking final images.

The in-house team also ensures that these are discoverable, accessible collections, and builds upon existing metadata, enhancing it where possible in consultation with curators and an editorial board. With the Service Newspapers collection, for example, the database includes notation of military units and theaters of war, as well as an interactive map for users to gain a sense of the geographic spread of materials. For the American Indian Newspapers, the team commissioned specialists to provide additional indexing for the newspapers in Indigenous languages.

Says Hemmings, “relationships with archives are at the center of what we do. That’s why we have projects where we return to work with our key archival partners again and again. It’s a massive privilege to look after this precious material.”

These databases also offer publishers an opportunity to hone relationships with the communities that produced or will use the materials. For the American Indian Newspapers project, Adam Matthew Digital “aimed to give back to those communities,” says Hemmings. To build trust with the newspaper publishers and secure necessary copyright clearance and permissions, the team visited tribal councils and publishers; Fehr initiated many conversations with publishers to build on established relationships and trust. The database has also been made available for free to all tribal colleges and universities in the United States—a decision that, Fehr said, distinguished Adam Matthews from other publishers.

These databases compile unique materials and presented unique challenges. For each of them, however, the publishers have made an effort to bring to light what makes these materials special and ensure they are available to a wider community of researchers.

Jennifer A. Dixon is Collection Management Librarian, Maloney Library, Fordham University School of Law, New York.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!