Beyond the Book: New Publishing Models and Online Platforms Feed Gen Z's Need for Free or Cheap Reads

New publishing models and online platforms feed Gen Z's need for free—or at least cheap—reading.

A recent survey of Gen Z users aged 16–23 conducted by LJ discovered that readers in this age group love hardcover books as much as previous generations, and get a significant chunk of their reading material from their library. But the survey also revealed that what they don’t get from the library—or purchase—comes from an increasing variety of sources, including online outlets that are not part of the library purchasing ecosystem. More frugal than even the Silent Generation, Gen Z has discovered that free and cheap online reading platforms like Wattpad, Scribd, and fanfiction repositories can fill their desire to read at low or no cost, while providing an experience that satisfies this generation’s strong desire for stories and characters that reflect its diversity.

For libraries to serve this up-and-coming generation, library workers need to understand the different platforms and resources available—and develop a methodology for providing access and reader’s advisory services for materials that are fluid in availability and scope and not part of the usual run of library materials, and may not be available for purchase and/or preservation by libraries at all.

FREE OR INEXPENSIVE SUBSCRIPTIONS

Many librarians are familiar with Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited service. It is not available to libraries, but can provide a cost effective way for voracious readers to access a vast repository (more than a million titles) of ebooks, magazines, and audiobooks. The catalog is limited to those authors, often (but not exclusively) self-published, who have signed up for the service. For anyone who reads more than one book a month and is flexible about which authors and titles they desire, its gigantic catalog and relatively tiny price tag ($9.99 per month but often discounted to much less) is a bargain.

Scribd, with more than a million readers signed up, is similar to Kindle Unlimited—at the same price point but with a somewhat smaller and slightly different catalog and with more emphasis on providing access to otherwise traditionally published materials. Scribd prides itself on providing access to material from Big Five publishers, where Kindle Unlimited emphasizes the vastness of its catalog of exclusive material. Both also include audiobooks and magazines.

Wattpad, however, operates in the space between the above services and fanfiction archives. While it launched Paid and Premium tiers last year, and does have some commercially published content available to its 80 million users, that content is mostly in the self-publishing space. Wattpad’s emphasis is on user-created content: some 400 million story uploads, including fanfiction. Beginning in early 2019, Wattpad launched a publishing arm, Wattpad Books, which mines its content for titles the company feels will see commercial success using their proprietary machine learning technology. Traditional publisher Macmillan handles sales and distribution in the U.S., Raincoast Books in Canada, and Penguin Random House Children’s in the U.K. Wattpad Studios, launched in 2016, mines the sites’ content for stories adapted for film and TV.

Samantha Helmick, Public Services Manager of Iowa’s Burlington Public Library, presented on the platform at the American Library Association (ALA) annual conference in 2017. She hosts workshops on Wattpad and how to publish on the platform, where writers can not only get in-person feedback but also experience the dynamics of online reader interaction, including bringing back a former teen patron now in graduate school to share her experiences on the platform. She urges other librarians to do likewise.

Samantha Helmick, Public Services Manager of Iowa’s Burlington Public Library, presented on the platform at the American Library Association (ALA) annual conference in 2017. She hosts workshops on Wattpad and how to publish on the platform, where writers can not only get in-person feedback but also experience the dynamics of online reader interaction, including bringing back a former teen patron now in graduate school to share her experiences on the platform. She urges other librarians to do likewise.

Beyond programming, she tells LJ that Wattpad is “deeply valuable as a library community even when it comes to collections,” partly because it models a crowdsourced folksonomy of creator-generated tagging, and community-led tagging norms, as opposed to professional, controlled vocabulary. Helmick asks if libraries are creating ways for users to bring their voices to library content in the same way. “The more we can be engaging in those conversations, and the more we can be looking for where can user content be generated to make our library collections more personal and meaningful to them, is probably gold,” she says.

Until that happens, Helmick points out that just knowing what is trending on Wattpad can be mined to fine tune library choices, especially if you get input from your own user base on what resonates locally. She knows of libraries whose staff “talk about tagging with their teen advisory groups and it influences how they market their book displays and endcaps.”

SPEAKING OF FANFICTION

There are two vast online repositories for fanfiction, the venerable Fanfiction.net (FFN) and the Hugo-Award winning Archive of Our Own, also known as AO3. Really large and vocal fandoms, such as “Harry Potter,” Star Trek, Doctor Who, Sherlock Holmes, and Jane Austen, to name just a few, also have their own dedicated fanfiction repositories.

Fanfiction is often derided as amateurish, and sometimes it is. But it can also provide perspectives on stories and characters not imagined by their creator, or not permitted by the mores of their time. Sherlock Holmes has been the subject of thousands of commercially published and often quite successful pastiches and adaptations. All could be labeled as fanfiction, but because most of the Holmes canon is out of copyright, they are commercially viable properties. Not that there isn’t plenty of Sherlock Holmes fanfiction (8,000+ stories between FFN and AO3) based solely on the original Arthur Conan Doyle stories. (This does not include fanfiction based on the movies, TV series, or later adaptations and pastiches, counted separately).

Fanfiction is also a medium in which writers can hone their craft using pre-established characters and settings to create scenes and stories that satisfy lovers of book series, TV series, movies, and games, and who are looking to extend their enjoyment of a beloved character or fictional world, as well as readers looking for something a bit different. While fandom is no more free of bias than the rest of society, fanfic tends to offer a greater degree of inclusive and diverse representation than traditional publishing—elements that are important to Gen Z readers.

Every library has heard the lament that a beloved series is finished but readers still clamor for more. While librarians offer read-alikes from their collections, if a patron is looking for something specific to Harry Potter, there are more than 800,000 Harry Potter stories on FFN—and another 200,000 on AO3.

Although FFN and AO3 perform similar functions, there are a few crucial differences between them. FFN is considerably older; it was founded in 1998. Better known than AO3, it has a larger and deeper archive of stories. AO3 was begun in 2009 as a reaction to FFN purging its repository of stories labeled MA, as “only for adults over 18 years old.” AO3 includes such stories, relying on its robust and granular tagging system to help readers find what they want.

The question of how libraries can and should deal with fanfiction has come around before and probably will again. A 2008 article in Public Libraries Magazine titled “Readers Advisory 2.0: Recommending Fanfiction” provides an overview of what fanfiction is and how libraries can use it to embrace readers “where they are” and for “who they are.”

At the same time, embracing fanfiction may conflict with librarians’ desire to defend copyright, as some fanfiction authors celebrate its status as outsider literature that does its best to make an end-run around copyright issues. (Others, such as the Organization for Transformative Works, which runs AO3, maintain that non-commercial fanfiction is fair use in the U.S.) It may help that fanfiction repositories restrict themselves to fanfiction about properties that have either enthusiastically embraced the phenomenon—such as J.K. Rowling with “Harry Potter”—or remained silent on the issue. Works inspired by titles whose authors are on record as being opposed are generally not included. Also, neither the repositories nor the authors make any money from fanfiction. They rely on donations and advertising revenue. Discussing fanfiction may also provide a teachable moment to educate users about copyright.

SHORT AND SWEET

While much of the content in the platforms above corresponds roughly to novels, short stories, and novellas in format, if not medium, there are also plenty of repositories for content that exists adjacent to the book space, both in libraries and outside them.

What Serial Box calls a series is different from what libraries call series. Instead of novel-length installments, they are more like TV series or the serialized novels popular in Dickens’ times—particularly series of science fiction, fantasy, or thrillers, although the company has now branched into classics such as Dracula and Pride and Prejudice. Serial Box produces both an ebook and an audiobook that are sold as a single unit, so that the reader/listener can switch seamlessly between formats as desired.

Becky Spratford, Illinois-based readers’ advisory librarian, trainer, and author, is enthusiastic about Serial Box for its range and flexibility. “Being able to switch between formats for the same story as fits your situation is fantastic. You can read the ebook and then if you have to drive somewhere, seamlessly switch to audio.” She also likes that Serial Box offers both “stories that are part of existing properties,” such as TV show Orphan Black or Marvel’s Thor, as well as original material, and that the company works with big name authors. “The serialization of the stories makes them perfect for readers who also enjoy podcasts,” Spratford tells LJ. “It is a similar reading experience to fans of the series podcasts like Serial. One story over multiple ‘chapters.’”

Unlike many of the platforms mentioned in this article, Serial Box tells Spratford the company does work with libraries. However, says Spratford, so far “the platform they have is not easy for libraries to use,” and the format presents a dilemma similar to that created by TV DVDs: Do libraries check out each chapter or an entire series at a time?

Serial Box is not alone in creating offerings in bite-size chunks. The ALA’s Library of the Future Initiative highlighted this trend as “Short Reading,” noting that in addition to Serial Box, Amazon and Audible have created their Kindle Singles, Singles Classics, and Audible Exclusives to hop onto this particular bandwagon, as has traditional publisher Little, Brown through the Bookshots initiative with author-publisher James Patterson. Penguin Random House cooperated with New York City’s MTA to launch Subway Reads. There’s even Short Edition, a company whose vending machines print out short stories timed as one-, three-, or five-minute reads on request.

STRONG VOICES

While powerful in combination, as at Serial Box, the increasing popularity of audio means it can stand on its own, and not only in book-length audiobooks. When it comes to recommending audio for Gen Z patrons, librarians should be familiar with popular podcasts and podcasting platforms. The word “podcast” combines “iPod” and “broadcast,” which encapsulates where the format began: with users downloading and listening to episodic broadcasts on their iPods. However, the format has outlasted and expanded far beyond the device. According to a report by Edison Research and Triton Digital, the number of people in the U.S. who have listened to a podcast jumped by 20 million from 2018 to 2019. Half of people ages 12 and over have listened to a podcast and 14 million people listen to podcasts weekly.

Podcasts can be about pretty much anything. Many exist somewhere in the book space, either as episodic broadcasts of stories—like Serial Box—or about books and reading, which are legion. Romance readers can listen to the Smart Bitches, Trashy Books podcast, while sf and fantasy readers can follow The Coode Street Podcast. Mystery readers can follow Limetown, and true crime aficionados can discuss Murder with Friends.

Podcasts can be about pretty much anything. Many exist somewhere in the book space, either as episodic broadcasts of stories—like Serial Box—or about books and reading, which are legion. Romance readers can listen to the Smart Bitches, Trashy Books podcast, while sf and fantasy readers can follow The Coode Street Podcast. Mystery readers can follow Limetown, and true crime aficionados can discuss Murder with Friends.

Libraries are themselves part of the podcasting environment. Library staff create podcasts in every state and on almost every continent. But the libraries that are out there creating podcasts do not necessarily preserve their own archive of podcasts—let alone anyone else’s.

Efforts are being made to change that. Preserve This Podcast (PTP) project, funded by a two-year grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, is helping preserve, protect, and provide access to the wide variety of podcasts being made. PTP produces its own zine about the project, as well as webinars, and includes an extensive list of resources in its own library to assist librarians in preserving podcasts—their own and, importantly, those of others.

“In terms of content, especially for marginalized populations, one of the biggest reasons podcasts are so important to the media landscape is that...you don’t have an agent or producer or literary agent saying ‘No, this isn’t good enough,’” Dana Gerber-Margie, co-lead of PTP, tells LJ. When it comes to the library’s role, “we’re interested in…local historical societies, local archives, and local libraries seeing and including podcasts under their collections policy just as they would with books or manuscripts or analog audio,” Gerber-Margie adds.

So far, PTP knows of very few places archiving podcasts institutionally. Creators can submit their RSS feeds to Podcastre, a research database developed and maintained by the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Sound Studies Department, and the Black Podcast Archive in 2018 crowd-sourced podcasts for preservation. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture added select episodes of the Revision Path podcast to its permanent collection.

A PLACE FOR LIBRARIES—AND LIBRARIANS

Libraries are already providing access to all of these services through public access computers and library Wi-Fi. Helping users locate the “good stuff” is the next logical step. The issue for podcasts, just as for all the book and story related services in this article, is that they exist in a fluid space that doesn’t play well with traditional library collection development practices. However, this does not mean that libraries don’t have plenty of readers/listeners who would love to have a “guide for the perplexed” that covers which of these entities might be worth their time and reading attention. Readers who cross comfortably between these formats and platforms to consume content will respond to recommendations that do the same, much as libraries offer read-alikes for movies and TV shows, and vice versa.

This isn’t the first time that libraries have tackled an issue like this one. It isn’t even the first time that libraries have tried to tackle pieces of this particular issue.

Before Fanfiction.net, before podcasts, before the internet, there were zines. Zines, short for fanzines, a portmanteau of fan and magazine, were self-published, fan-created, and fan-oriented publications originally devoted to individual fandoms. Originally fanzines were printed (usually on a mimeo machine), published, and distributed to groups, often of science fiction and fantasy fans. They tended to be short in run, small in distribution, and labors of love.

As the precursors of FFN and the content, if not the format, of many podcasts, they were published outside the mainstream and were difficult for anyone outside their communities to discover. Libraries who wanted to collect and preserve these small artifacts of history faced an uphill battle finding actual issues and providing access to them.

|

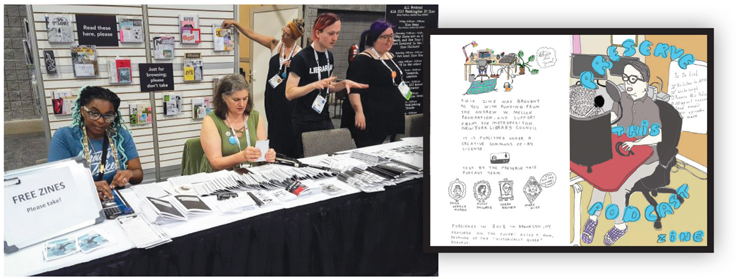

LIBRARIANS TAKE THE LEAD Volunteers and organizers give out zines at the 2019 Zine Pavilion at ALA Annual in Washington, DC; Preserve This Podcast Zine tells libraries how to save this new format |

Jenna Freedman, Associate Director of Communications & Zine Librarian at Barnard College Library, tells LJ that while zines have moved away from their fandom roots and into more creative nonfiction and activism, the medium and its unique challenges continue. And she draws some parallels between her zine work and podcasts in particular.

“One of the major similarities is working with living creators, which may be less common in special collections.”

Gerber-Margie of PTP agrees. “I see it as ideally a relationship between preservationist and the creator, working out agreements, like would an archive save the podcast creator’s research files as well, or would they just save the final MP3 that went out to the public?”

Lessons learned from Zine libraries, the Zine Librarian Unconference, and the Zine Pavilion in the ALA conference exhibit hall, provide examples of process and products that are relevant to creating collections of—or at least access to—material from outside the mainstream, as well as articulating the reasons for doing so.

Some librarians are already taking on the challenge of curating and contextualizing these phenomena, though so far mostly in the academic rather than public space. A Google search for “LibGuides Fanfiction” or “LibGuides Podcasts” turns up a host of resources on those topics—everything from how to start podcasting from the University of Michigan Library to specific subject listings of podcasts like the Biology: Science Podcasts list from Georgia Tech or Eastern University’s guide to philosophy blogs and podcasts.

While the podcasting LibGuides are as much about the how-to as the subjects of the podcasts, the repository of LibGuides surrounding fanfiction is rich and robust; it varies from scholarly research about the wide range of the topic (at the Ithaca College Library) to lists of fanfiction repositories to works on the intersection of fanfiction and marginalized communities housed at from Montana State University–Billings.

(NOT) THE LAST WORD

Most services described here are outside mainstream publishing. While that means avoiding some built-in quality control mechanisms, it can give voice to many who would not otherwise participate in traditional publishing, whether it’s because their interests are too niche, their identities marginalized, or simply because there isn’t, yet, a place for them to feel at home. For libraries and librarians to remain central to the evolving reading ecosystem, we need to be ready, able, and willing to help users find what they want to read on these new platforms and their successors, as well as in our own catalogs.

Marlene Harris is the founder of and primary reviewer for the book review blog Reading Reality. She has been an LJ reviewer since 2011 and has written several articles for Library Journal.

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!